When referring to “skeletons in the cupboard” we rarely expect these to be literally true, but in the case of Mary Ann Higgins and the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum in Coventry, it is.

In the early 1970s the Herbert acquired an unusual and unique object – the head of the penultimate woman to be hanged in Coventry. In 2009, after nearly 40 years in a box, she was displayed in the museum for the first time. We have used this as a platform for internal and external debates on retention and display of human remains and their status as a museum object. Key to our approach to giving access to her is detailing her context and story before giving visitors a choice whether to view her head or not.

In 1830 Mary Ann Higgins was living with her uncle William in Coventry. Around Christmas that year she began courting a watching apprentice, Edward Clarke. Over the next couple of months Edward spent money freely and boasted “I have only to go to the old man’s house whenever I want money”.

St John’s Church, Coventry, 1823 by Edward Rudge. This church stands at the end Spon Street, where Mary Ann and her uncle William lived. Mary Ann claims that she and Edward Clarke were due to marry there two weeks after the murder took place.

On 22 March 1831 Mary Ann bought arsenic from the chemist to kill rats. That same night William fell ill and died. After a neighbour became suspicious of two differently coloured soups, tests found arsenic in William’s stomach and in one soup. After initially denying knowledge of the poisoning Mary Ann then admitted to adding arsenic into one bowl of soup. She told the coroner that Clarke had encouraged her to take her uncle’s life, and that Clarke had frequently beaten and ill-used her when he did not have as much money from her as he wanted.

After an inquest in Coventry the pair were committed to trial at the Warwick assizes on 9 August 1831. After 11 hours and the examination of over 40 witnesses the jury convicted Mary Ann and acquitted Edward. As the judge sentenced Mary Ann to death, her cries moved onlookers to tears. She was hanged two days later in front of 15,000 people.

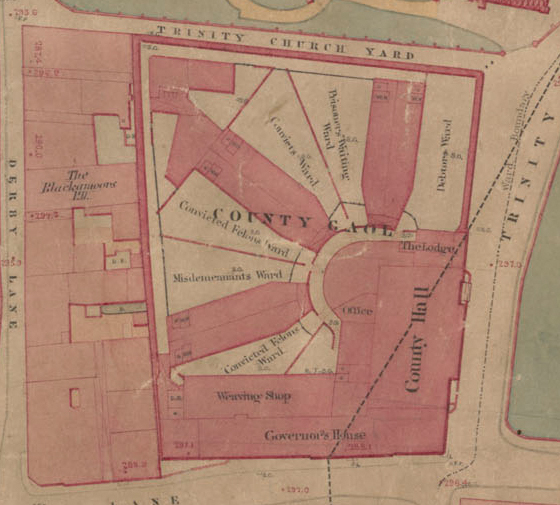

Coventry Gaol, Board of Health Map, 1851. Coventry Gaol was built in 1831 to replace the decrepit Old Bridewell. It was from here Mary Ann began her last journey to Whitley Common, the site of the gallows.

The next day surgeons performed an initial dissection on Mary Ann’s body which was then displayed to the public. All this detail (and more!) we know from contemporary newspaper reports – the crime was published in papers around the country and even featured in the Newgate Calendar.

Her journey from dissection to the Herbert has to be pieced together from more limited information. After the dissection Mary Ann’s head was preserved. Today skin and cartilage remain on her skull as does a waxy substance that was injected into the veins around her scalp. Her head was probably retained by the police surgeon and we know that she was displayed in Coventry in 1919, as a curiosity. There is no trace of the rest of her body. Her head was eventually willed into private hands and from there acquired by the museum.

The Hour of Death exhibition at the Herbert in 2009. The Hour of Death examined the lives, crimes and punishment and context of the last two women to be hanged in Coventry. Mary Ann’s skull was shown, with warnings, behind the white structure at the back of the room.

Since 2009 the Herbert’s approach to holding Mary Ann’s remains has been to contextualise them with her story and the wider setting of poisonings, crime detection and punishment as well as medical access to human remains. Recent research has revealed further details of about her family, and that she was christened Ann in Henley-in-Arden on 13 January 1814.

However, there’s still a wealth of information to learn about Mary Ann both directly from her remains and more traditional historic research. We certainly need to put her crime and remains into the context of the wider British picture. I would welcome any insights readers may be able to offer.

Ali Wells is Curator of Natural Sciences and Human History at the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum in Coventry. Ali’s areas of interest include George Eliot’s time in Coventry and women’s fashion from 1800 to the present. Her first exhibition at the Herbert examined the stories of the last two women to be hanged in Coventry – Mary Ann Higgins and Mary Ball. More recently Ali has curated exhibitions on the history of children’s television in Britain and on local wildlife.

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Recent Comments