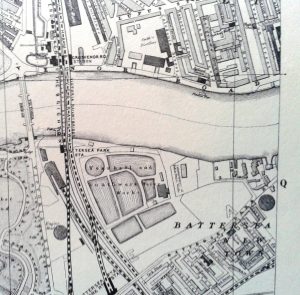

Battersea, London. Source: The A to Z of Victorian London. Harry Margary, Lympne Castle, Kent, 1987.

One of the most disturbing unsolved murder mysteries in London’s history began on the morning of 5 September 1873 when a Thames policeman rowing on the river found the left quarter of a woman’s torso in some mud off Battersea waterworks. On the same day other policemen found the right side of a woman’s torso floating in the water off Brunswick Wharf, and portions of lungs at Old Battersea Bridge and near Battersea railway pier. The next day a woman’s face with scalp attached was found off Limehouse. On 8 September a right thigh was found in the Thames off Woolwich and a right shoulder with part of an arm off Greenwich. These body parts were reassembled on a mechanical frame and examined by the police surgeon for the local division, Dr Kemspter. His preliminary findings were that the woman appeared to be around 40 years old, she had thin and short dark hair, a thin moustache, and her left breast bore a scar from an old burn. Kempster told the inquest that the blow to the head was likely the cause of death.

Thames Division of the London Metropolitan Police Force on duty near Tower Bridge. Source: http://www.thamespolicemuseum.org.uk/gallery.html

Reports of the discovery caused a sensation and scores of people visited the workhouse to see if they could identify the corpse, a melancholy indication of the numbers of missing middle-aged women in London at the time. One man searching for his married daughter was shown the “ghastly face”, stretched over a butcher’s block, and seemed to recognize it, but he did not remember his daughter having a scar on her breast. Rumours quickly circulated that this was a joke by some medical students gone wrong, as the body was not hacked but was “dexterously cut up”. Other theories at the time were that the woman was a victim of the bargemen on the Thames or that she been murdered by some criminal lunatics who had escaped from Broadmoor, although reports of the dismemberment indicated that some skill was required. The left half of the pelvis had been divided by cutting through the spinal column through the right side, near the lower ribs, and attached was a portion of the bladder. In the meantime body parts continued to be found along the Thames west of London Bridge at ebb tide: a left foot, a piece of the right arm, and two legs (ankle to knee).

Photographs of the body were taken, leads were chased up and a reward of £200 was offered for information, but there was no breakthrough or criminal profile in the case. The hands and skull were never found, perhaps kept as trophies by the murderer or to prevent identification, but it is likely that the woman was one of the many thousands of London’s prostitutes who were at a heightened risk of male violence on a daily basis. On 21 September the unidentified body was buried at Battersea cemetery, although her face was preserved at the workhouse by its medical officer.

This case is a good example of a modern type of homicide, carried out in a metropolitan centre in which victim and perpetrator could live disconnected lives within the same social space. For the perpetrator, dismemberment served to disguise the identity of the victim and limit the availability of clues, but it was also a spectacular presentation in a culture increasingly enthralled by spectacle and sensation. In contrast with other cases of dismemberment homicide in Victorian London (e.g., James Greenacre’s murder of Hannah Brown in 1837; Kate Webster’s murder of Julia Martha Thomas in 1879) the “torso murderer” was an organized offender who treated the body parts of the victim not as a problem, but as objects in a game with the authorities. The victim was deconstructed and denied burial, but the perpetrator exhibited a strong desire for attention in spreading fragments along different parts of the Thames, presenting the police with “pieces of a puzzle”. Indeed, it is probable that the same killer struck again in June 1874 when the decomposed remains of a woman, lacking head, arms and feet, was found floating on the Thames near Putney. There may have been other victims whose body parts were undiscovered, ignored, or misidentified amid the routine stream of human and animal remains in the river.

Brutal dismemberment murders continued to occur in London. Charles A. Hebbert, an assistant police surgeon, examined the body parts of two dismembered victims found in the Thames in 1887 and 1888. In his case report, Hebbert mentioned the difficulties that investigators had with gaining meaningful information in dismemberment cases that also involved submersion in water. These included: difficulty in identifying age; height; condition in life; and even gender in cases where torsos and heads were missing. Although one suspects some male investigators would have missed key clues on the body of female victims due to lack of general knowledge of feminine hygiene and undergarments, Hebbert did note that one of the legs found in July 1887 showed that “garters were worn below the knee, a custom, I believe, more common among the lower than the upper classes, who either wear garters above the knee or suspenders”. In the cases he examined, Hebbert noted that the neatness of the disarticulations he examined demonstrated the skill of a butcher or hunter.

If we take into account the torso murders of 1873-4, 1887-8, and the more famous Whitechapel murders of 1888, it seems apparent that there were at least three serial killers operating in London in the later nineteenth century who dismembered working-class female victims. All three killers appeared to have taken care in planning the attacks, targeted a similar type of victim and butchered the bodies in a controlled orchestra of violence. These crimes raise questions about the social, psychological, and environmental contexts which assist or deter such sadistic behavior.

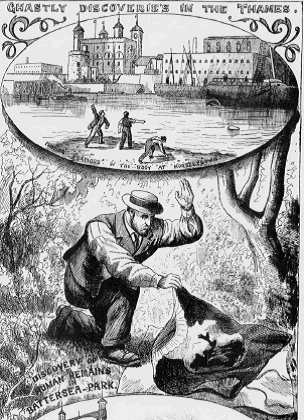

Dismemberment murder of woman, Battersea Park, 1889 – the last victim of ‘Jack the Ripper’? Source: Illustrated Police News, June 15, 1889

Dismemberment is a practice which has a long evolutionary history. In my previous blog I showed how dismemberment was meaningful in myth, warfare, and ritual. Dismemberment, like serial killing, is both an age-old phenomenon and a modern social construction which make sense to us through accepted discourses of crime and psychiatry. In the pathological framework used by many to understand homicidal dismemberment today it is mostly explained not through collective myths, veneration, or burial rites, but simply as the desire of an abnormal individual or small group of abnormal individuals to desecrate the body or conceal the identity of the victim, and thereby the perpetrator/s.

It would be an interesting project to investigate how far back in the historical and archaeological record this type of criminal dismemberment stretches, although Phillip L. Walker suggests that any prehistoric serial killers would have been identified and killed “if they were foolish enough to redirect their homicidal urges closer to home and away from the socially sanctioned killing of outlaws and dehumanized ‘others’”. The question therefore is not “why do some humans dismember other humans?”, but rather “what are the social contexts which allow, prohibit, or facilitate this activity?”

Shane McCorristine is an interdisciplinary historian with interests in the ‘night side’ of modern experience – social attitudes towards dreams, death, hallucinations, and the supernatural. Shane was a Wellcome postdoctoral fellow on the ‘Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse’ project at Leicester and is the author of William Corder and the Red Barn Murder: Journeys of the Criminal Body (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Recent Comments