Almost four years ago to the day I travelled to Leicester to attend my first PhD supervisory meeting armed with only a pen, a notepad and a head swirling with ideas. When I walked out of that meeting I was nervous yet excited about the mammoth task of getting to grips with such a large and complex subject area, I asked myself where do I start? The only logical answer was to jump in head first! I read everything and anything I could find about crime, punishment, executions and dead bodies. I began delving into research repositories including the Scottish National Archives and the British Library Newspaper Archive in order to trace the malefactors who received a capital punishment for their crimes and to chart their journey from the courtrooms of Scotland, to the execution scaffold and finally to either the dissection table or the gibbet cage. I explored a host of weird and wonderful beliefs about death and the disposal of the body. I found cases where condemned criminals and their relatives would go to great lengths to avoid facing a post-mortem punishment including crying out from the scaffold, stealing bodies from their gibbet cages and even sending bodies to a watery grave in the sea.

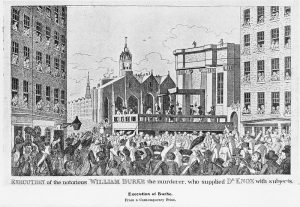

Despite these beliefs and fears over the disposal of the body the public execution and, to some extent, the post-mortem punishment of the corpse attracted large and diverse crowds of people. Whether the crowd’s attendance at the foot of the gallows was motivated by a morbid curiosity, a desire to see an offender punished or even to show sympathy for their plight and whether the condemned malefactors faced the hangman’s noose with stoicism or trepidation they all had a part to play in this piece of state theatre. Along my PhD journey I encountered a range of criminals including perhaps Scotland’s most infamous murderer William Burke. Following his execution for murdering 16 people in order to sell their bodies to a professor of anatomy, in an ironic twist of fate, his body was publicly dissected in Edinburgh and attracted a similar sized crowd to the one that had attended his hanging. Despite the public revulsion for the motivations for his crimes, they flocked to see his partially dissected corpse laid out in Alexander Monro’s anatomy theatre. His case, more so than any other in Scotland, met the aims of the 1752 Murder Act, namely to add a further degree of infamy to the punishment of death.

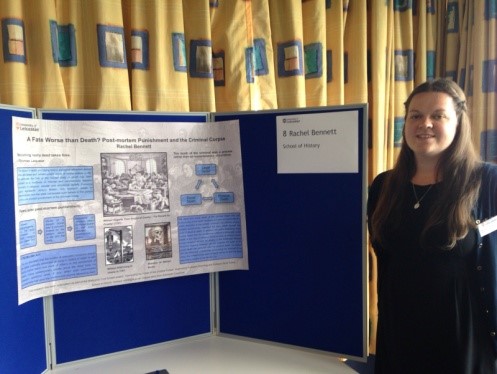

I presented my research at various conferences, seminars and other events and was able to discuss my topic with a range of people from diverse research and employment backgrounds as well as with friends and family. I was met with a range of reactions including avid interest on the part of some but a slight shudder at the mention of dismembered corpses around the dinner table by others.

Photographed by the author at the University of Leicester’s annual Festival of Postgraduate Research in July 2015.

When the plethora of information and sources that I had gathered steadily turned into a mountain of papers, folders and half-ideas littering my desk and saved in hundreds of separate word documents that I somehow had to shape into a PhD thesis the adage, ‘you cannot see the woods for the trees’ had never seemed so apt! However, after countless hours staring at a blank screen and re-writing the same sentence over and over to get it just right and experiencing every emotion from anger and frustration to sheer elation when something finally clicked into place, the chapters of the thesis slowly took shape. In October 2015, at the end of three years that had both flown over and yet seemed like a lifetime in parts, I finally submitted my PhD thesis and soon after passed the viva examination.

Due to the broad and expansive nature of the history of capital punishment and the criminal corpse, the completion of my doctoral thesis has marked the beginning rather than the end of my fascination with the subject area. I am currently in the process of exploring numerous research strands and writing up a number of publications, the ideas for which originated in some form or another over the past four years, and I still have that same excitement and desire to dive head first into the topic that I had when I walked into that first PhD meeting.

Dr Rachel Bennett completed her PhD entitled ‘Capital Punishment and the Criminal Corpse in Scotland, 1740 to 1834’ after a fully-funded studentship as part of the Criminal Corpse project. This post includes some of her research for a forthcoming chapter: ‘A Candidate for Immortality: Martyrdom, Memory and the Marquis of Montrose’ in Shane McCorristine (ed), When is Death?: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Death and its Timings (Palgrave: Forthcoming 2016).

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Recent Comments