Today is officially the first day of summer, and I welcome the season this year particularly grateful for something that this time last year hadn’t even crossed my mind. Thank goodness Britain no longer practices gibbeting! Between the bouts of monsoon-style rain, the sun is bursting through here in Leicester making for uneven lurching between chill and heat (but it’s damp, always damp). Can you imagine what effect these beaux temps would have on a body hanging in chains? If you, like me, are cursing your parents right now for taking care to encourage your active and imaginative mind, good luck. Chances are that you’ve never smelled something so foul, but nonetheless, go ahead and imagine the bloated, rotting corpse of the dead man standing on air this fine June day.

The view north from the Combe Gibbet, Berkshire (UK). This country can be so beautiful (particularly when you look AWAY from the gibbet). Photo by Joolz. 2004, Wikimedia Commons.

Elizabeth Hurren has written on the synaesthesia of dissection in the 18th and 19th centuries in her new, soon-to-be-released book: Dissecting the Criminal Corpse: Staging Post-Execution Punishment in Early Modern England. Elizabeth explores in vivid detail the complex and sometimes overwhelming sensory experience of witnessing or participating in the journey of the criminal corpse from the gallows to the slab – first to the parody of dissection performed to satisfy the execution crowd, then to the more private rooms and theatres of the anatomists. The sensory experience of the gibbet (at least, for the living) is explored by Sarah Tarlow in her forthcoming book, The Golden and Ghoulish Age of the Gibbet in Britain. She describes the way bodies were left on the gibbet because they were too disgusting to bring down, and the year that one community spent unable to open their windows because of the stench rolling off a nearby gibbet.

But the gibbet is a contradiction that refuses resolution: life and death are both emphatically present, neither capitulating to the other. Death is easy to identify in this tableau: the body of the executed man, the implied threat that this could be you if you fail to learn from his example, and the macabre effect of the clanking chains as the cage moves in the wind. But the gibbet is also the epicentre of abundant life: the defiantly jubilant and carnivalesque crowd that gathers to partake in the spectacle, the birds that circle, call, and perch, and the buzzing insects nourished by and multiplying in the body. At the intersection of life and death, stands the man – literally. Common to all the gibbet cages examined by Sarah Tarlow in her comprehensive study is that the gibbeted body was suspended in a standing position. This upright posture creates an unnatural impression of life even in the face of obvious death, and was uncanny and unnerving to those who passed by.

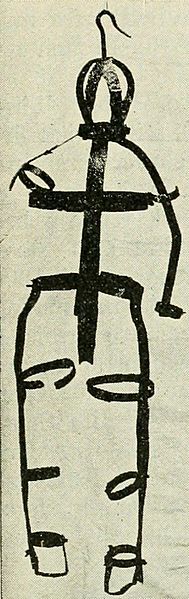

You may notice that I’m mixing my verb tenses today. Take it as a sign of my confusion about where past and present begin and end due to my current immersion in the life stories of three gibbets. Gibbet cages were part of the technology of a spectacular post-mortem punishment in the 18th and 19th centuries, but some have lived much longer (and some, more interesting) lives than the individuals whose corpses they were constructed to hold. Take, for example, the gibbet cage of Marie-Josephte Corriveau – an extraordinary case and the only one I know of in which a woman was gibbeted. Hanged for the murder of her husband in 1763 in Quebec just after the British conquest of Nouvelle-France, the corpse of Marie-Josephte was hung in chains for five weeks from April into May on orders handed down from the military governor at the time, James Murray. When the cage was brought down, it was buried in a nearby churchyard and rediscovered in the mid-19th century due to renovations to the church and churchyard. The gibbet cage of “La Corriveau”, as she came to be known, became an immediate object of interest and toured Montreal, New York, and Boston where people paid to see this ghoulish curiosity. In the 20th century, the cage ended up in a museum in Salem where it remained for decades, largely forgotten. In 2013, however, the cage again became an object of intense interest and in 2015 “la cage de la Corriveau” was confirmed to be authentic, and was repatriated to Quebec.

The gibbet cage of Marie-Josephte Corriveau. From the Visitor’s guide to Salem, Salem, Essex Institute, 1916.

In many ways, the gibbet is still with us today. Depicted in popular films and games, part of historical “edutainment” in local museums and displays, and emphatically present in stories, poems, and objects associated with hanging in chains, rain or shine, there’s always the gibbet.

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Recent Comments