Eighteenth-century London has, with good reason, been called “the city of the gallows”. Gibbets lined the approach to London in every direction, not least of which at various points along the Thames, where offenders sentenced to death by the High Court of Admiralty for crimes committed on the seas were hung in chains after being “launched into eternity” at Execution Dock in Wapping.

William Clift’s drawing of hanging at Execution Dock. Archives of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, MS0283/3. Permission granted by RCS. http://publishing.rcseng.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1308/147363507X193993

Indeed, the judges of the Admiralty court made prolific use of hanging in chains, both for killers sentenced under the 1752 Murder Act, and for those executed for a range of other crimes, including piracy, mutiny, sinking ships and serving on enemy privateers. The Admiralty court gibbeted a greater proportion — some 46% — of its convicted murderers in the years 1752–1832, more than any other court with equivalent numbers of convictions. And the 23 offenders gibbeted by the Admiralty court for non-killing offences in the same period dwarfed the 8 cases ordered at the Old Bailey.

Why did the judges of the Admiralty court make such frequent use of hanging in chains? In the case of executed murderers, it might have been in part due to the difficulties of carting the corpse along the 3 mile journey back from Execution Dock to Surgeons’ Hall in the Old Bailey for dissection, surrounded by the crowd of thousands that regularly turned up to the event. Gibbeting in this sense was easier, since the bodies were transported instead up-river by boat.

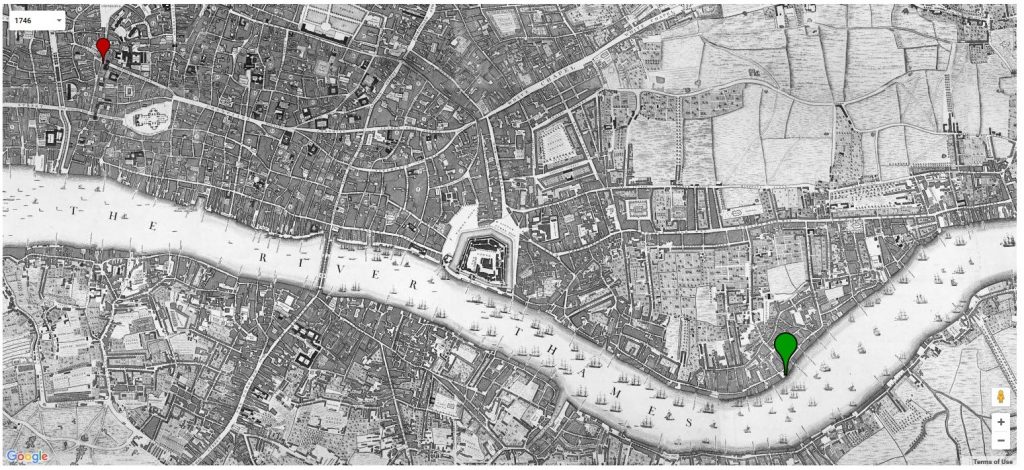

1746 map of London, showing the location of Newgate (red) and Execution Dock (green). Locating London’s Past, http://www.locatinglondon.org/ (version 1.0, accessed 13 April 2016), mapping “Newgate” and “Execution Dock” onto Rocque’s 1746 map of London.

But more importantly it seems was the cold, brutal “logic” of the Admiralty judges in their desire to make terrifying, visible examples of offenders in order to maintain the British state’s order and authority over its rapidly expanding overseas empire, particularly at moments of apparent crisis. In 1814, for instance, four Malayans convicted of murder at the High Court of Admiralty were ordered — instead of dissection — to be hung in chains “near the place of their execution, as an example to others”.

This fearsome expression of power and authority seemed to be especially required in cases of piracy and mutiny. In 1781 the Admiralty board complied with the application of the mayor, corporation and merchants of Yarmouth for the corpse of William Payne to be transported from London and hung in chains there, so that “by his example others may be deterred from committing the like piratical depredations”. Payne’s gibbet remained on the coast at Yarmouth for some 23 years.

Depiction of a hanging at Execution Dock. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Executiondock.jpg?uselang=en-gb

It was a policy of severity that the authorities followed in spite of criticisms and overt opposition from some quarters. A number of gibbets were pulled down, a scene that was caught in a fascinating sketch of 1827.

For William Dykes, writing to the Home Secretary, Robert Peel, in 1824, the skeletons hanging in chains along the Thames were a nuisance and a disgrace:

“I am sure you will overlook the intrusion of a letter from a private individual calling your notice to the continuance of the revolting spectacle exhibited on the bank of the Thames, and which excites feelings of disgust in the hearts of numerous voyagers to Ramsgate, Margate, France, the Netherlands, etc etc. I allude to the scare-crow remains of the poor wretches who long since expiated by death their crimes, now hanging upon gibbets. It is said that “persecution ceases in the grave” let these poor remains find a grave, and the remembrance of their offences pass away. I have heard many ladies anxiously enquire if the boats had passed the gibbets, and not until then would they come upon deck. I have heard seamen say “what honest man would like to have a halter held up to him in menace, and why should they (following their lawful and honest employ) have the hint thus injuriously prolonged to them?.. The offences were not, if I remember rightly, peculiar to [the port of London], but merely the Admiralty jurisdiction is here held. The remains of mortality is a sad sight under any circumstances, under such circumstances it is revolting, disgusting, pitiable, dishonourable to the Law’s omnipotence, and discreditable to the administrators of the Law.”

Such was the “Thames scenery” in the city of the gallows.

Richard Ward is currently a Research Associate at the University of Sheffield, working on a major, interdisciplinary project, The Digital Panopticon: The Global Impact of London Punishments, 1780–1925 (http://www.digitalpanopticon.org/), funded as part of the AHRC’s ‘Digital Transformations’ programme. Richard’s first monograph, Print Culture, Crime and Justice in Eighteenth-Century London (Bloomsbury, 2014), provides the first detailed study of crime reporting across a range of eighteenth-century publications (including newspapers, the Old Bailey Proceedings, Ordinary’s Accounts and graphic prints) to explore the influence of print upon contemporary perceptions of crime and upon the making of the law and its administration in the metropolis.

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Recent Comments