Last year I visited a fine old building nestled incongruously close to the skyscrapers and busy financial offices of Market Street in downtown Philadelphia. The building houses the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the oldest private medical organisation in the United States (founded in 1787). Today, Philadelphia’s heyday as the centre of medical and scientific education in North America has passed, but the College of Physicians remains a draw for those interested in the history of medicine through its historical library, medicinal herb garden, and its medical museum. This museum was founded by a College Fellow, Thomas Dent Mütter (1811-59), in 1858 and its remarkable collection of skulls provides me with an opportunity to briefly reflect on some of the themes that we have raised in the Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse project at Leicester.

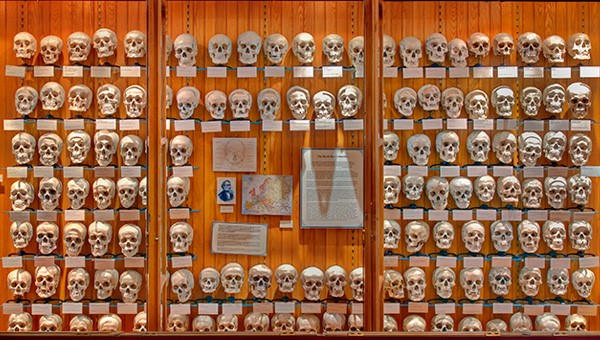

Thanks to a travel grant from the Wood Institute I was able to spend a week at the College of Physicians where its Mütter Museum houses many famous bodies and specimens. These include the “Soap Lady” (a preserved body exhumed in 1875), a slide collection of sections of Albert Einstein’s brain, and a cast (and the livers) of Chang and Eng Bunker, Siamese twins who settled as farmers in North Carolina in the 1840s. However, the museum is perhaps best known for the Hyrtl Skull Collection, made up of 139 human skulls acquired from the Viennese anatomist Josef Hyrtl (1810-94) in 1874. This exhibit – nicknamed the “Grinning Wall” – is a stunning example of how the display of bodies and body parts can enthral as well as disgust. It raises issues about the ethics of collecting, displaying, and contextualising the criminal dead.

Hyrtl’s collection was made up of the skulls of named suicides, executed criminals, and people who died in asylums and other institutions – but many were of unknown origin. They came mostly from graves and anatomy rooms in Central and Eastern Europe and Hyrtl was upfront about the fact that many skulls were obtained through theft and sourced from his former medical students who worked in Ottoman-controlled lands. So why bother collecting skulls? Hyrtl practised anatomy in an era of “cranioklepty”, when medical professionals, and those on the fringes of medical orthodoxy, obsessively collected the skulls of the dead in order to determine if racial, ethnic, or social characteristics were cranial in origin.

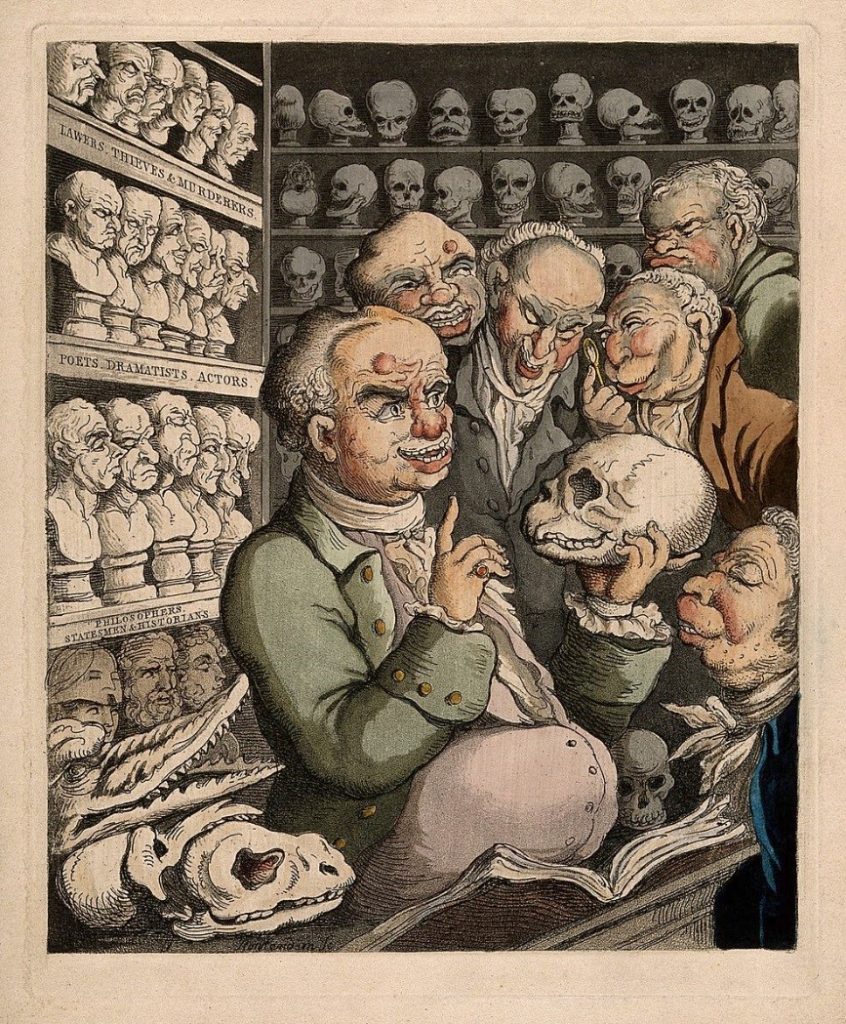

The most infamous iteration of this quest came from Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828), a German physiologist who argued that human characteristics were revealed in the size and shape of the skull. Although Gall is still celebrated as a pioneer of brain science, he and his followers – known as phrenologists – were particularly interested in “deviations from the norm”, that is, the skull types of geniuses, celebrities, madmen, and criminals. In order to determine baselines for “normality”, phrenologists needed a large amount of measurements from a wide variety of human skulls and this led to the commercialisation of skull and cast collections, and the grave-robbing and theft which underpinned them. Between 1790 and 1850, almost no celebrated criminal or genius in Europe was safe from the attentions of phrenologists, eager to make a death mask, pilfer a skull, or take cranial measurements before burial.

While the skulls of creative “types” such as Hadyn, Beethoven, Swedenborg, and Mozart were notoriously stolen and traded during this period, the fate of the skulls of criminals is interesting for what it tells us about the particular ideas about criminal bodies that were circulating during the period. Gall’s own collection of skulls and casts, now mostly at the Musée de L’Homme, Paris, contained specimens of over one hundred criminals. The catalogue listing gives us an idea of what they were intended to demonstrate:

Skull 5600-4-2-3. A soldier who was executed for having killed a prison guard. The organisation which produces proud, unmanageable personalities who cannot bear authority, is very noticeable here.

Cast 5624-35-3-8. A young Prussian boy of fifteen who had an irrepressible tendency toward stealing. He died in a reformatory where he was to spend all his life. Seen before last condemnation by Gall, who considered him incurable.

Skull cap 5756-35-4-2. A very shrewd thief. A lunatic?

Phrenologists constructed hierarchies of cranial types and the criminal was an important piece in the jigsaw of their unscientific and prejudiced system. As one phrenologist wrote:

The crimes that disturb society, and people our jails and penitentiaries with culprits, are murder, theft, assault and battery, fraud, treason, arson, and rape; and these are the product of five unrestrained animal propensities; Destructiveness, Combativeness, Acquisitiveness, Secretiveness, and Amativeness. Let these propensities be held in due subordination, by the higher faculties…and the crimes referred to will cease to exist.

Hyrtl – a Roman Catholic – was opposed to phrenology, and he collected skulls in order to demonstrate the variety of cranial shapes within ethnic groups, as well as the plasticity of the skull in response to circumstances. However, although his work originated out of an anti-phrenological impetus, Hyrtl engaged in the exact same unscrupulous collection methods as the phrenologists. He had no sense of the ethical implications of his practice and sold his collection to the Mütter Museum for the large sum of 6,410 Prussian Thalers.

In our work as individuals and as a collective, the Criminal Corpse team at Leicester have picked at the thorny issues surrounding the collection of body parts of the criminal dead. We realised that body parts were inherently mobile objects, moving swiftly between legitimate and illegitimate spaces in a manner analogous to the organ theft business today. We also argued that the curation and possession of criminal body parts had a particular value (or a lustre, a glamour, or an aura) for the owner, possibly due to cross-cultural ideas about the transference of power at the moment of an untimely death.

And so, my visit to the Grinning Wall was an uncanny experience because I read that it has its origins in anti-phrenology and yet it raised the very same ethical problems that haunt collections like Gall’s. One feels that parts of so many people have been neatly put together on shelves with little in common, apart from their collective designation as “abnormal”. Hyrtl did not provide much information on the skulls beyond that which he inscribed on the skulls. Here are some examples of the sparse details of the criminal dead:

Kasimir Ostrowsczynski, aged 30, Russian, for the crime of grave insubordination, died under the most cruel scourging.

Veronica Huber, Salzburg, aged 18, executed for murder of her child.

Giulio Tombolani, age 28, died in prison of Gaeta, brigand.

Ladislaus Pal, reformist, guerrilla, and deserter from Transylvania, executed by hanging

Constantin Jacic, age 24, Serb, executed by hanging, robber and murderer.

There is a huge amount of scholarship on the ethics of displaying human remains, much of it emerging in the context of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act in the USA (1990), the Gunther von Hagens’s Body Worlds exhibitions (1995 – ), and the Human Tissue Act in the UK (2004). Museums that display body parts of the criminal dead today must therefore deal with issues of consent and context. Where did the remains come from and how? In what way should they be presented, if at all?

It was good to see the Mütter Museum attempting to subjectify their skulls. They did this through a well-publicised “Save our Skulls” campaign that asked visitors to donate $200 to adopt a skull and pay repairs and new mounts. This succeeded in raising funds for the museum, but also allowed members of the public to cultivate intimate attachments to “their” skulls, based around repeat visits. It seems to me that their attempt to generate new narratives around the skulls echoes the work that we have done in providing historical and philosophical context to debates about the criminal dead. We have looked at how remains were objectified, commercialised, and fetishised. We have looked at the timings of death and the ways in which criminals lived on medically, socially, and politically after they were executed. We have also looked into the folk, legal, and social histories of criminal punishment and dismemberment in a manner that is – to use the slogan of the Mütter Museum – “disturbingly informative”. People are attracted to the criminal dead and it would be disingenuous to deny that researchers, funders, and museum curators do not also trade in this glamorous currency. It is hoped that the outputs from the Criminal Corpse project help other researchers make sense of why this attraction is disturbing, but also why careful historical research on the subject is so necessary.

Shane McCorristine is an interdisciplinary historian with interests in the ‘night side’ of modern experience – social attitudes towards dreams, death, hallucinations, and the supernatural. Shane was a Wellcome postdoctoral fellow on the ‘Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse’ project at Leicester and is the author of William Corder and the Red Barn Murder: Journeys of the Criminal Body (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Recent Comments