The main objective of the ‘Carceral Archipelago’ project has been to write the history of convicts and penal colonies into global history, by synthesizing existing research on some geographical contexts with new work on others. My edited volume, A Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies, published in May 2018 , represents an important step in achieving this goal.

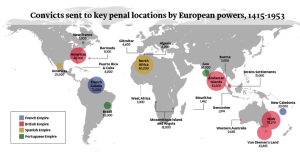

The book presents a series of chapters, which cover the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, Scandinavian, French, British and Russian Empires, as well as Japan, Europe, the USSR and the post-colonial nations of Latin America, and, together, the essays span the period 1100 to the present day. Each is written by an expert in the field. The volume is richly illustrated, including with maps commissioned out of the research findings of the ‘Carceral Archipelago’ project. These maps can be read alongside the ‘Infographic’ below, or the ‘pins’ on the project’s interactive online map, which is freely available on our public-facing website, http://www.convictvoyages.org/

When I conceptualised the scope and form of the volume, and commissioned the essays, I had in mind one aim. That aim was that scholars interested in issues such as imperial expansion, the extension of national frontiers, migration, coerced labour and the history of punishment would not be able to write without taking the history of convicts and penal colonies into consideration. The first stage in this endeavour was mapping convict flows, and connecting them to key events in world history. The second was offering a first attempt to enumerate globally convict mobility. The third was suggesting that the scale, volume, character and timeframe of transportation flows was such that the key narrative in the history of punishment is not the rise of the prison, as is usually claimed, but the mass relocation of criminalised populations for labour purposes (even when small, convicts could form majority populations). In regards to this argument, the fourth was arguing that convicts built – literally – the infrastructures of connection that made the modern world. With many ex-convicts settling in colonies and frontiers, penal transportation was a form of coerced migration that has left profound demographic, cultural and environmental legacies.

Within this grand historical narrative, the volume has endeavoured also to read the often-fragmentary sources on penal transportation for evidence of convict agency, resistance and creativity. In some cases (e.g. Portuguese Empire, Meiji Japan), there exist remarkable contemporary memoirs, authored by convicts. In others (e.g. British and French empires), detailed and meticulous record-keeping practices reveal glimpses of convict perspective. This has enabled the authors of the volume to discuss inter alia convict escape and mutiny, cultural formation, and alliances between convicts and other kinds of workers, including soldiers and the enslaved. In this regard, the chapters represent a collective effort to combine analysis of large-scale global transformation with an approach rooted in history from below. It is important to recognize that convicts were not solely subjects of systems of transportation and penal labour, but shaped them in important ways. Our contention is that the global history of convicts and penal colonies can only be written as a global history from below.

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Recent Comments