By Anna McKay, AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Partnership Student, National Maritime Museum & University of Leicester.

In 1775 the outbreak of the American Revolution halted the transportation of felons to the colonies. One year later, with gaols overflowing, the Criminal Law Act -also known as the ‘Hulks Act’- was passed. Convicts awaiting transportation were put to hard labour on the shores of the Thames and stationed on floating prisons knows as hulks. Prison hulks were decommissioned warships, stripped of their masts, rigging and sails. The subject of my own doctoral research, hulks occupy an interesting position in the history of the nineteenth century British prison system. They were both social and restrictive spaces, and are famed for their reputation as ‘hell on water’ epitomised.

Hulks were moored up along the Thames and Medway estuaries, as well as at Portsmouth, Bermuda and Gibraltar. In these locations, the work of convicts increased the efficiency of dockyards. Yards were in a constant state of evolution and needed to keep up to date with the latest technologies, such as the advent of steam power and iron-hulled ships. Convicts provided a cheap and efficient workforce, and rather than build new barracks to house men, prison hulks could be acquired at little cost and towed from site to site. A day in the life of convicts on board hulks differed from their counterparts in land prisons due to the nature of their confinement. Daily routines were more naval than penal. However, over the eighty-year period of their operation, discipline and routine on board the hulks began to reflect reforms which took place on land.

Morning

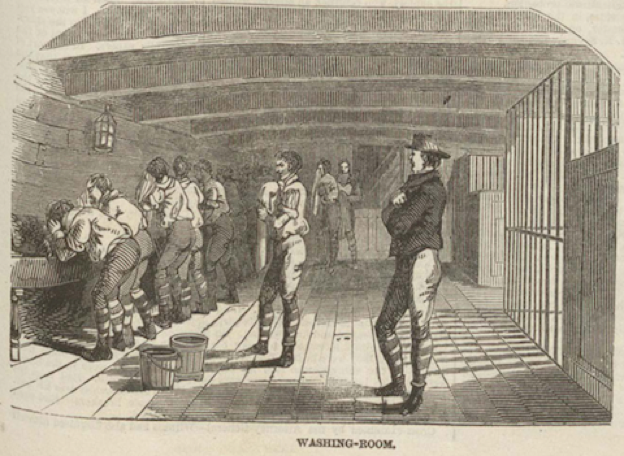

Up at five in the morning, convicts rolled up and stored their hammocks. The wards were then unlocked and the men washed themselves in water troughs and dressed. Uniforms were important as they distinguished convicts from common labourers in the dockyards. Breakfast consisted of 12 ounces of bread and one pint of cocoa. Eating was a silent affair: in 1862, Henry Mayhew visited the Defence hulk. He remarked, “The men were all ranged at their tables with a tin can full of cocoa before them, and a piece of dry bread beside them, the messmen having just poured out the cocoa from the huge tin vessel in which he received it from the cooks; and the men then proceed to eat their breakfast in silence, the munching of the dry bread by the hundreds of jaws being the only sound heard” [i]. After breakfast, the men were employed in a thorough cleaning of all decks of the ship until 7.30am.

With the ship in good order, men were mustered out of the hulks in gangs and rowed out to work in the dockyards. They were received on shore by officers, quartermasters and guards. Old and infirm convicts stayed behind to cook, clean and repair worn out shoes and clothes. Across the water in the dockyards, the work of healthy men varied. Generally, convicts were put to work unloading ballast and timber from ships. They moved cables, dredged channels and shifted rubble. All men were required to wear a heavy chain on one or both ankles at all time. If they misbehaved, the weight of their leg irons would be increased.

Afternoon

At lunchtime, all convicts returned to the hulks to eat. After one hour they were ferried back to the yards to continue their work. The process of loading, unloading, and marching convicts to work twice a day generated criticism. An 1831 Select Committee report pointed out that so much time was lost in the process that convicts actually worked two hours less than free labourers every day [ii]. Unlike their counterparts in land prisons, convicts moored on hulks and stationed in the dockyards were able to converse with free labourers. Efforts were made to separate convicts from fellow workers but interaction was near impossible to avoid due to the nature of labour. Without communication, work could not be carried out effectively, and many men suffered terrible injuries when safety was compromised. The falling of stone and timber resulted in broken arms, legs and amputations. Death was not uncommon, and was often covered up by officials.

Prisoners were prevented from working in bad weather as it was thought unsafe to send them onshore on dark and foggy days. Escape attempts were feared, and men were routinely searched by overseers. Mayhew observed, “Here the officers proceeded to search under the men’s waistcoats, and to examine their neckcloths, so as to prevent the secretion of clothes about their persons, which would enable them to disguise themselves, and to escape among the free labourers. No less than seventeen such attempts to escape had taken place among the “DEFENCE” convicts in one year, though out of these only three got off.” [iii].

View near Woolwich in Kent shewing [sic] the employment of the convicts from the hulks, c. 1800. Printed for Bowles & Carver. Call No. V*/Conv/1. State Library New South Wales.

Evening

Work finished at 5.30pm. Convicts were rowed back to the hulks and were permitted to wash before supper was served. The average dinner allowance of each convict on the Defence hulk at Woolwich in the 1860s was listed as “6 ounces of meat, 1 pound of potatoes, 9 ounces of bread” [iv]. Convicts regularly complained of bad provisions; contractors were often corrupt, and general mismanagement meant that complaints could go unheeded for many months. After dinner, convicts were expected to participate in evening prayers and schoolwork. Men could leave the hulks with more skills than they had arrived with. In 1817, William Tate, the Chaplain on board the Captivity and Laurel hulks at Portsmouth, wrote to superintendent of the hulks, John Henry Capper, that the schools in both his hulks were flourishing. Tate declared that many prisoners under his care were now writing “a good hand, who were unable to read when they first gave their attendance” [v]. The drive for education came from the belief that it could prevent reoffending, but learning to read and write after a day of back-breaking labour in the dockyards was hardly relished. By eight o’clock, the weary men were mustered one last time before bed. Lamps were extinguished and hatches locked at nine. Until the later years of the convict hulk establishment, ships were not divided into cells. Prisoners could therefore roam the deck freely at night, engaging in conversations, sexual relations and arguments, as well as buying and selling illicit goods such as alcohol and tobacco.

Conclusion

Unpacking the image of prison hulks as ‘hell on water’ is a complex task. Convicts faced many hardships; living and working environments came with their own risks, the threat of transportation loomed large, and separation from friends and families was reinforced by isolation from land. However, Irish political prisoner John Mitchel believed that some Englishmen purposefully committed crimes in order to exploit the hulk system, declaring that “hulking, as a profession, is as yet confined to England; [and] it will become a more favourite line of business there, as the poverty of the English poor shall grow more inveterate” [vi]. When men grew destitute and faced the workhouse, life as a convict was measured out against the negatives of offending. After all, prisoners were provided with three meals a day. They mastered trades and learnt to read and write. When released, they were even given a little money. Nevertheless, government officials made every attempt to make life on board as punitive as possible. After a series of scandals, the prison hulk system wound down and was officially disbanded in 1857. It was an eighty-year tenure, but their legacy as dark, dangerous spaces has far outlived them.

Footnotes:

[i] Henry Mayhew and John Binny, The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of London Life, (London: 1862), 215.

[ii] House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, Select Committee on Secondary Punishments, 1831-32. Paper No. 547, Vol.7.

[iii] Mayhew, Criminal Prisons of London, 217.

[iv] Mayhew, Criminal Prisons of London, 215.

[v] House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, Reports Relating to Convict Establishments, 1817. William Tate to John Henry Capper, 10.

[vi] John Mitchel, Jail Journal; or, Five years in British Prisons. (New York, Published at the Office of the Citizen, 1854), 141.

__________________________________________________________________________

Anna McKay is a third-year collaborative doctoral researcher based at the University of Leicester and the National Maritime Museum. Her Arts and Humanities Research Council funded project is entitled, “The History of British Prison Hulks, 1776-1864”. Anna intends to produce a new reading into the history of British prison hulks, with a particular emphasis on the social and cultural lives of prisoners, both convicts and prisoners of war.

@AnnaLoisMcKay.

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

Recent Comments