The Iglesia de la Merced, in Quito, was built in 1737 on the remains of the original church that dated from 1538 – four years after the foundation of the city.

The church is situated in the city centre, at less than one kilometre distance from all other main sites of the colonial period: the Cathedral, the churches of the main religious orders (the Franciscans, the Augustinians and the Jesuits), and the main governmental site: the Palacio de Carondelet, once the headquarter of the Audiencia de Quito and today’s official residence of the President of the Republic of Ecuador.

The foundation of the Iglesia de la Merced was connected to the missionary activities of the Order of Mercy (and the Mercedarians), created in 1218 by Pierre or Pere Nolasco “to redeem Christian captives from their Muslims captors” (http://orderofmercy.org/the-mercedarians.html). From Catalonia, both the Order and the devotion of the Virgen de la Merced (Virgin of Mercy) spread out to the rest of the Spanish peninsula, France and Italy during the late Middle Ages; during the colonial conquest, it reached Central and South America and in the Philippines, and acquired a special importance in the Andean region.

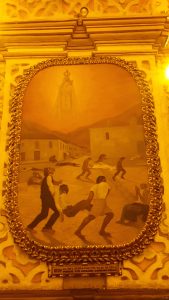

A series of paintings made in the early 1930s hang on the pillars of the Iglesia de la Merced.

This collection tells the story of the relationship between the Virgin and the city, and the country at large. Honestly, their artistic quality is not striking (and the quality of my pictures is not any better). However, their interest lies in the fact that they include two levels of narrative. On the one hand, through the Virgen de la Merced – Patroness of the city of Quito, Guayaquil, and of the Ecuadorian army – we are reminded of some founding moments in the institutional history of this region:

On the other hand, the paintings explore the popularity of the Virgen among the city’s population, and particularly its most humble milieu. In this way, they provide us with some snapshots from the social life of the city. Unsurprisingly for anyone acquainted with devotional paintings, this part of the story is dominated by catastrophic events and the providential interventions of the Virgen.

The caption of the last painting of this series reads: “1760 Leaving Cadiz, one ship burns in flames, which were put out using Your image”.

This clearly called my attention, since Cadiz in the second half of the eighteenth century was not only a primary commercial hub in the Spanish empire, but also the single most important node of transoceanic convict transportation. Moreover, thinking about how Quito was connected with the far-away Andalusian port, I was immediately reminded of the two regional routes of convict (and trade) transportation of that period: once the sailing ships arrived in the port of Cartagena de Indias – in present-day Colombia – the convicts were either transported by land across the Viceroyalty of New Granada, or by sea and land via Portobelo (or Chagres), Panama and Guayaquil. There regional voyages were equally dangerous, and therefore multiplied risks such as the one described in the painting.

There can be little doubt that the anonymous painter did not think about convicts while producing these pieces of art. He (or she?) did, however, implicitly point to that feeling of powerlessness that is so often reflected in the humble petitions of the convicts to the King and the Viceroys. That kind of feeling and fatalism which produced the quest for protection: from the Virgen and from authorities that were often referred to by means of religious expression.

However, there is another part of the story that is totally excluded from the narrative of these paintings, revealing their implicit “pedagogic” goal towards the subaltern classes. For the petitions, as well as court cases and other historical sources, make us aware of the agency of those subaltern groups, including the convicts. They tell us that convicts sentenced to transportation did influence the decisions regarding their destinations through those humble petitions. And they reveal how they manipulated and subverted the religious messages aimed at their control and repression, in order to empower themselves and understand and change their (often incredibly difficult) lives. In other words, whereas the paintings in the Iglesia de la Merced were certainly designed to transmit a top-down and over-simplified idea of the (Catholic) religion, we as scholars need to be aware of the multiple and contradictory ways religion was transmitted and experienced. Indeed, this is what I thought this morning, visiting some of the magnificent churches of Quito, as I heard two priests giving opposite interpretations of the parable of the Good Samaritan – one conservative and the other almost revolutionary – and observed the devotional acts of some of the inhabitants of this fascinating city.

Subscribe to Christian De Vito's posts

Subscribe to Christian De Vito's posts

I would have liked to have heard what the two priests were saying. It’s a shame you didn’t repeat it here. Your article was very interesting.

Dear Nigel, thank you. I will pass this on to Christian. Best wishes, Clare

Dear Nigel, many thanks for your comments, and please accept my apologies for this late reply.

You are right, more details about the preaches would have been appropriate in the blog post. The main differences regarded the interpretation of the figure of the Samaritan. For the first priest – the “progressive” one – he symbolised all migrants and refugees, and highlighted not just compassion, but active solidarity. Solidarity then had come from a stigmatised migrant, rather than by the other elite passers-by, including a clergyman. What made it his preaches especially radical were also the series of contemporary examples he gave regarding both practices of solidarity and cases of exclusion and repression. He drew them not only from the context of Ecuador, but also from cases of Latin American exiles from Argentina and Brazil during the dictatorships of the 1960s-1980s, and of the refugees who died in the Mediterranean sea during their recent voyages. In all cases he foregrounded not only the solidarity towards migrants and exiles, but also among them.

The “conservative” priest limited himself to a strictly philological analysis, with some explanations of the historical background but absolutely no reference to present-day circumstances.

Best wishes,

Christian