At the end of last week, thirteen Nobel prize-winning scientists wrote a letter to the right leaning newspaper The Daily Telegraph, urging Britain to vote ‘remain’ in the forthcoming European Union (EU) referendum. The scientists warned of the consequences of a British exit (or ‘Brexit’) from the EU, drawing attention to the fact that it allocates billions of Euros of funding to researchers in the EU every year (via an organisation called the European Research Council, or ERC). This, they argued, enables British researchers to stand at the forefront of health, innovation and economic growth. It promotes the movement of people and ideas, facilitating exchange and collaboration. They concluded: ‘The prospect of losing EU research funding is a key risk to UK science.’

The research funding of which they write is, of course, allocated out of the tens of millions of pounds that Britain and other member states pay into the EU each week. (The exact sum that Britain contributes is disputed by the ‘remain’ and ‘leave’ campaigns.) ‘Leave’ campaigners seized upon this, arguing that Britain has little say in the allocation of this money, and pointing to the success of non-member nations (notably Norway, Iceland and Israel) in securing a share of it. Notwithstanding disagreements about Britain’s financial contribution to the EU, and the relative success of member/ non-member states in funding allocations, it is the case that researchers are successful or otherwise at the end of a rigorous application, peer review and (sometimes) interview process. It is highly competitive; researchers from all over the world assess the merits of each application, and it is not unusual for less than less than 5% of applicants to be successful. Note also that the non-member states that secure a portion of this resource contribute financially to this (and other) EU programmes.

I write this blog as the director (or in research-speak ‘principal investigator’) of a large European funded project: The Carceral Archipelago. In 2012, on a second attempt, and after months and months of preparation, I submitted an application to the ERC. It was assessed, favourably, by some of the most eminent historians in the world; and I was called to Brussels to appear in front of and answer questions from a panel of 15 top researchers from across Europe and North America. Gruelling it most certainly was, but the rewards have been great. I was allocated €1.5 million of research funding to spend over a five year period to do the research required to construct the first ever global history of convicts and penal colonies, from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries, in locations all over the world.

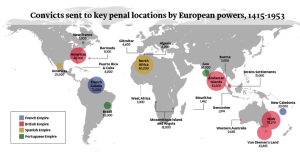

Our work is mapping the global scale of penal transportation – including by European powers

Our work is comparing the use of convicts for colonisation purposes – including in the British Empire (black line) and British Asia (grey line)

My work is not science; and I will never win a Nobel Prize. However, it will change fundamentally the way in which we view the history of the world since the 1400s (notably by stressing that violence and forced labour extraction underpinned globalization), and it will enable us to understand better some of its legacies and continuities in the present day (for instance, Indigenous dispossession.) Judging by the volume of invitations that I get to speak about my findings in universities in Europe, Africa, North America and Australasia, and from the scale of public engagement with the project’s website and blog, and my Twitter feed, this work has been of huge interest not just to professional historians and their students, but to the general public. The ERC has funded my salary and the cost of research in archives and former penal colony locations. It has paid the salaries and travel costs of a team of researchers working in various languages and on a range of global locations; collectively, we read, speak and write in English, French, Russian, Spanish, Dutch, Italian, and Japanese. It has paid the costs associated with our offices and access to university facilities. It has paid the cost of setting up and resourcing the project website, www.convictvoyages.org, which is freely available to lecturers, students, and others. It is paying the cost of publishing our research in ‘open access’ format. This means that anybody can read and engage with our work – not just those with access to university libraries, or subscriptions to academic journals.

Our work is studying penal colony locations all over the world – including in Moulmein, Burma (pictured here)

Additionally, the ERC has enabled me to oversee the training of the next generation of History research students and researchers, as they forge their own careers in learning, teaching and public engagement. History remains a hugely popular choice for university study by some of the brightest and best young people in Britain today, and the fact that students get to interact with cutting-edge researchers in universities is what makes them such different learning environments to schools. Judging by the diet of radio and television alone, the burgeoning of online resources designed for family historians, and the popularity of magazines like History Today (in which I published All The World’s A Prison), the general public too is enamoured with History.

Our work is training the next generation of research students and researchers – PhD student Katy Roscoe presenting her work

It is interesting that buried a little deeper in the weekend’s news, at the same time that the scientists’ letter to The Daily Telegraph was grabbing the headlines, was a fascinating story about research that had discovered the existence of a vast network of cities, concealed beneath the jungles of modern Cambodia. Incredibly, these cities would have made up the world’s largest empire in the twelfth century. This truly amazing work, we learned, has been funded by the ERC.

I do not believe that in the event of a Brexit the British government would use any of the savings from what it currently pays into the EU to resource the funding currently won from the ERC by researchers in British universities. Neither do I believe that we can count on EU members’ generosity in enabling a nation that has voted ‘leave’ to sign the kind of reciprocal agreement that has allowed some non-member states to access ERC funding.

But the purpose of this blog is not to scare voters concerned about universities and the intellectual life of the nation into ticking the ‘remain’ box on June 23rd. The purpose of this blog is to remind us all of the enormously positive benefits of EU membership. Britain’s membership of the EU has been and will remain vital to securing the vibrancy of the arts and humanities in British universities, to educating and training our young people, to understanding the past, and to enriching cultural life – and in securing our influence across Europe and all over the world.

![019PHO000001099U00026000[SVC2]](https://staffblogs.le.ac.uk/carchipelago/files/2016/06/019PHO000001099U00026000SVC2-300x201.jpg)

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Recent Comments