By Mikhail Nakonechny.

The late Imperial Russian prison and exile system is almost unequivocally considered to be the traditional embodiment of brutality, institutional inhumanity and injustice. The popular image of endless convict suffering in vastness of Siberia, supported in the English speaking world by the influential George Kennan’s work on Siberian exile[i] and enhanced by classic Soviet historiography on the matter (M.Gernet[ii], B.Utevskiy[iii] etc.) persists in the public Western and Russian mind to this very day. Countless narrative sources written by the political prisoners of the tsarist regime in 1880-1917 and popularised during the Soviet period, seem to prove that such sentiments are justified[iv].

What is often overlooked in the literature on late Russian Imperial prisons is the fact that the most anachronistic rudiments of XVIII-century inhuman practices were slowly discarded step by step throughout the XIX century (closely following western humanitarian efforts in the penal sphere), although the tendency was often non-linear and Russia sometimes lagged behind. Furthermore, global penal reform of 1879 and its consequences is generally underestimated or even simply overlooked by contemporary historians, who tend to make generalizations and value judgments based exclusively on memoirs, without analysis of statistics. That nuance leads to a situation in historiography when assertions, which are valid and justified for Russian prisons of the 1880s, are mechanically imposed on later chronological periods. Such incorrect methodology distorts the actual development of late Imperial penitentiaries over a longer period of time.

As B. Adams effectively put it in his monograph: ‘Russia’s penal system has an extremely negative reputation . . . For most of the tsarist period there were good reasons for this . . . For the last forty or fifty years of the tsarist regime, however, [this reputation] is undeserved….Long after Russia had abolished most of these “anachronisms”, the reputation for backwardness remained’.[v]

In this blog I am not arguing with the undeniable fact that the Russian penitentiary and Siberian exile system (especially in the 1880s and the earlier period) was, as a whole, sometimes extremely brutal and deadly, but I would like to add a little bit of differentiation to that enduring stereotype.

To illustrate the existence of a trend of comparatively lenient modernization and to capture the essence of gradual change for the better, I intend to draw attention to the quantitative side of an almost forgotten but at the same time one of the most impressive achievements in the sanitary reform of the Russian exile system. It concerns the dramatic decline of relative mortality in the deadliest segment of Russian penal transportation – the so-called ‘transfer system’ of forced exile marches from the European part of Russia to Siberia and the Far East.

Jakobi V.I. ‘Prival arestantov’. (Convicts’ rest), 1861.

To contextualize, it is necessary to briefly describe the archaic Russian Imperial transportation system and its unique role in the correctional policy of the state[vi]. Being the largest country in the world and a huge landlocked Empire, Russia, in drastic contrast to other Imperial powers who often transported their delinquents to overseas colonies, sent convicted criminals and administrative exiles from the European part of the country to remote areas of the Siberian wilderness. The journey was conducted via a sophisticated system of so-called ‘transfer prisons’ and hundreds of temporary barracks (called etap and poluetap), built along the infamous Main Exile Path, where exile parties and their guard stayed for the night.

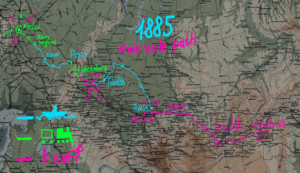

For example, in 1885 the Main Exile Path began in the Moscow transfer prison, where all convicted and administrative exiles were concentrated. Then the parties of inmates went through Nizhniy Novgorod to Perm, Kazan , Tyumen, Tobolsk, Tomsk, Achinsk, Irkutsk and, finally, Transbaikal region – where the Nerchinskaya katorga (hard-labor) complex was located.

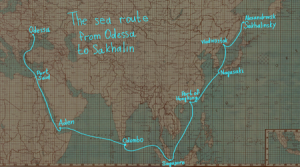

The transportation procedure itself was complicated and expensive- an average of 11,200 people (almost half of them women and children) were sent annually over the Ural Mountains to the inhospitable lands of Eastern and Western Siberia in 1880s, while some convicts from 1879 onwards were transported via the steamships of the Voluntary Fleet from Odessa to Sakhalin penal island on a long and often dangerous voyage.

In the first half of the XIX century, penal transportation in Russia was conducted exclusively on foot (occasionally on carts for the ill, elderly, political prisoners, women and children).

This circumstance provoked almost never-ending suffering for the chained parties of emaciated convicts, who quickly turned into a symbol of depravation in the social consciousness. To ameliorate the situation, in 1858 a first party of convicts was officially allowed to travel by a newly built railroad. Additionally, infamous prison barges were employed to sail the great Siberian rivers. But the Russian railroad infrastructure was still rudimentary, so it changed little at the time. In the early 1800s transportation itself was poorly administered, and although some measures were taken by the officials and society in 1820-1870 to improve penal logistics it remained in deplorable condition right into 1880s, when westernized penal reform finally began to take place in Russian Empire. Travelling convict parties consisted of various categories of exiles but not exclusively. The law allowed, under specific circumstances, that the wives and children of the inmates had the right to travel with them to their place of confinement and penal settlement in Siberia and the Far East – an attempt to colonize the vast and underpopulated frontiers of the Empire.

Lack of proper medical care, insufficient food, exposure , unsanitary conditions in filthy and poorly kept facilities on the way and, last but not least, typically extreme overcrowding in transfer prisons provoked the rampaging epidemics of incurable infectious diseases, such as typhus.

The journey was painstakingly hard, took almost a year in the first half the XIX century and was especially detrimental for children, who constituted the majority of deaths along the way[vii].

For all these reasons there were staggering sickness and mortality rates in the transportation system during the 1820s-1880s. As a matter of fact, it was just 5 or 6 transfer prisons (including the infamous Tomskaya Peresylnaya Tyurma and several others) that demonstrated the highest relative death rates in the entire system of approximately 800 prisons. They were the deadliest prisons in the whole Russian Empire for many years.

It is interesting to point out that in the West and in Russia itself the image of the katorga (hard-labor prison) is traditionally associated with elevated death rates and misery of the convict life.

But careful statistical analysis of mortality data inside different parts of the late Imperial penal system shows a completely different pattern. Although it may seem counter-intuitive to a superficial observer, figures of sickness and mortality convincingly demonstrate that forced foot marches from one filthy and overcrowded etap to another were, on the average, much more dangerous for the health and welfare of a Russian exile than incarceration itself (with a few notable exceptions of so-called katorga centrals of the 1870s and 1880s , located in the European part of Russia, which were also extremely deadly).

Mortality comparison proves that conditions in Siberian, Sakhalin or European katorga hard-labor prisons, however bad in 1880-1917, with a few isolated exceptions, were never as deadly as in the ‘transfer system’ of the 1880s and early 1890s.

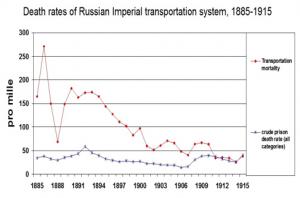

To illustrate the argument, let us look at Graph 1.

Sources: Wheatcroft S.G. The crisis of the late Tsarist penal system // Challenging traditional views of Russian history. 2002. PP. 27 – 54. See also Otcheti po glavnomu tyuremnomu upravleniyu 1885-1915. Spb-PG.

We can see that the death rate inside the 5-6 transfer prisons (out of nearly 800 correctional institutions of all types in the entire Empire) was hovering around extreme 15-20% per annum in the 1880s. That index of excess mortality was much higher than system average crude death rate. Of course, it is necessary to point out that, judging by the sex-and-age distribution data, almost half of the dead inside the penal transportation system were comprised of children under the age of 5 (voluntarily following their parents to exile), so direct comparisons of ordinary prisons and transportation system data, without adjustment to sex and age, are misleading. But still, these figures were one of the most gruesome and dark sides of penal exile under the Russian Old Regime, criticized by contemporaries.

On the other hand, during the second half of the 1880s, with implementation of modernized penal reform, significant positive developments began to slowly commence. The death-index experienced a radical decline in the 1890s (correlated with the opening of the Trans-Siberian railway), until it reached a record low of 2-3% per annum for the entire existence of prison system in Russian Empire in 1912-1914, while at the same time all the other prison types experiences a very serious crisis during 1908-1912. This does not mean, of course, that even after the lowering of mortality, the conditions inside the transportation system had become truly humane, but still the change for the better was unique in historical context.

As for the main reasons behind this fundamental improvement, S.G. Wheatrcroft explained them in his valuable paper:

‘The decline in mortality in the tsarist transportation system is undoubtedly related to the discontinuation of forced marches to the place of exile, of the incarceration of prisoners in the unsanitary conditions of the transportation forts (etap and poluetap) and the concentration and holding points, and on the infamous prison barges. Although transportation by rail in what came to be known as ‘Stolypin wagons’ had a very bad reputation, it replaced something that was very much worse. The main factor in reducing mortality here is probably the reduction of time spent in the gruelling and unsanitary conditions of this transportation system. The material indications of reduced mortality indicate the great improvement in health and welfare that was taking place at this time.’[viii]

All in all, the death rate in the 1910s transportation system was approximately 6-10 times lower then it was in 1880s (depending on the year). That major amelioration of the archaic transfer system was truly unprecedented in the whole history of Russian exile and needs to be emphasized as an important achievement of Russian penal modernization, which is not really well-known in the specialized literature or public mind. Static popular images of the late Russian Imperial transportation system of 1880s, described by G. Kennan and many other contemporary witnesses are still very influential.

Again, quoting Bruce Adams: ‘Our minds, colored by the knowledge of very real horrors, move from Kennan to Solzhenitsyn, and it seems as though thing only went from bad to worse. The brief period in which, for better or worse, reformers did modernize Russia’s prisons is buried in the much greater mass of information about the ills of the system over a much longer period’.[ix]

Although Imperial Russian prisons never had the chance to become effective and completely humane correctional institutions, the level of their inhumanity fluctuated dramatically in time and space and from one type of incarceration to another. It is always useful to differentiate and analyze statistical data to reach more nuanced conclusions.

[i] George Kennan, Siberia and the Exile System, 2 vols (New York: Century Company, 1891).

[ii] Gernet M. N. Istorija carskoj tjur’my. V 5 t. / Izd. 3-e. T. 1 (1762–1825). M., 1960; T. 2 (1825–1870). M., 1961; T. 3 (1870–1900). M., 1961; T. 4. Petropavlovskaja krepost’ (1900–1917). M., 1962; T. 5. Shlissel’burgskaja katorzhnaja tjur’ma i Orlovskij katorzhnyj central (1907–1917). M., 1963.

[iii] Utevskij B.S. Sovetskoe ispravitel’no-trudovoe pravo: Tjuremnaja politika carizma i vremennogo pravitel’stva.. M., 1957.

[iv] They are very numerous. See, for example, Katorga i ssylka periodical journal.

[v] Adams B. The Politics of Punishment: Prison Reform in Russia 1863-1917.DeKalb: North Illinois University Press, 1996.P.3.

[vi] For a more detailed account of Russian transportation system in XIX century see : Tagancev N. S. Russkoe ugolovnoe pravo. Chast’ obshhaja. Tom 2. – S.-Peterburg, 1902; Obzor dejatel’nosti Glavnogo tjuremnogo upravlenija za 1879 – 1889 gg. S-Peterburg, 1889.; Ssylka v Sibir, ocherk ee istorii i sovremennogo polozhenia. Dlya Visochayshe utverzhdennoy komissii o meropriyatiyah po otmene ssylki. Spb.1900.; Materialy dlja ugolovnoj statistiki Rossii. Issledovanija o procente ssyl’nyh v Sibir’ E. Anuchina. Ch. 1. Tobol’sk, 1866; Jadrincev N. M. Statisticheskie materialy k istorii ssylki v Sibiri // Zapiski IRGO po otdelu statistiki. 1889. T. 6. — S. 309 — 395.

[vii] Otcheti po glavnomu tyuremnomu upravleniyu, 1882-1900, SPB.

[viii] Wheatcroft S.G. The crisis of the late Tsarist penal system // Challenging traditional views of Russian history. 2002.P.39.

[ix] Adams B. The Politics.P.7.

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

hello i am researching my family tree and one story we have is an ancestor of ours went to russia to work on the trans siberian railway and was wondering if you could point me in the direction as to where i might find records etc best wishes elaine clayton

Dear Elaine, I am so sorry I really do not know where these records would be. Best wishes, Clare