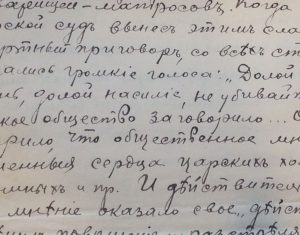

Last year I came across a rare archival find: multiple editions of a 19th century prison newspaper covertly produced by Russian inmates between 1890 and 1905. The newspaper editions, now brittle paper manuscripts fraying brown along their edges, were archived along with a note of introduction by the editor-in-chief. The editor describes the way in which the secret newspaper had covertly circulated via sympathetic guards from cell to cell, allowing numerous prisoners to add their own thoughts as well as read those of others. The prisoner-editor had carried, upon his release, the concealed manuscripts through Europe before sending them to a colleague abroad. Fifty years after his death, he wrote, the newspaper could be made available, again, to readers.

The experience of slowly paging through the leaves of curling, pre-revolutionary script, of translating the fading lin es of political commentary and poetry—remnants of those incarcerated by a regime long gone—leads me to reflect on the enduring importance of individual literary expression to those in prison, on the luxury that words represent for those temporarily silenced from society. I have discovered, in the course of my research, that even when confined criminals had little hope of their words reaching outside readers, many nevertheless took pleasure—and saw value in—creating a record of their lived penal experiences. Letters home were censored, incoming mail was delivered sporadically, and reading and writing materials scarce and often regulated. Still, despite the constraints of space and politics, prisoners often still managed to record their experiences in the written word.

es of political commentary and poetry—remnants of those incarcerated by a regime long gone—leads me to reflect on the enduring importance of individual literary expression to those in prison, on the luxury that words represent for those temporarily silenced from society. I have discovered, in the course of my research, that even when confined criminals had little hope of their words reaching outside readers, many nevertheless took pleasure—and saw value in—creating a record of their lived penal experiences. Letters home were censored, incoming mail was delivered sporadically, and reading and writing materials scarce and often regulated. Still, despite the constraints of space and politics, prisoners often still managed to record their experiences in the written word.

Prisoners’ poetry

Consider the case of the Russian prisoner today known simply by his bandit name, Pashchenko. Pashchenko was sent to Sakhalin island from the Odessa region on a life sentence for having committed thirty-two murders. Housed in Aleksandrovsk prison, he and his cellmate were chained to wheelbarrows to prevent their escape.

Despite their fetters and wheelbarrows, Pashchenko and his cellmate did escape from the prison: they dismantled their stove, used its components to break their chains, and left their cell through a hole in the roof. The two then fled across the island, hiding in coal mines during the day.

During the ensuing search, Pashchenko was shot and killed by a prison official. His life, however, is preserved in the notebooks of poetry he kept while in prison. One of these small volumes was found, bloodstained, in the pocket of the coat he was wearing when shot.

Pashchenko loved trivia and craved knowledge; subsequently, parts of his notebook are simply collections of random facts: “there are 497 people in Russian monasteries (269 men, 228 women);” “Sweden and Norway—two states under one crown; five million residents occupy the Scandinavian peninsula.”[1] Other pages, however, are full of poetry, much of it composed by Pashchenko himself.

Where were you,

when in confusion

I set upon a new path,

When this heart needed encouragement

Like a beggar needs bread?

Where were you,

when enemies punished me by degrees

And I, finally, lost belief in spiritual, brotherly love?[2]

In 1899, the Russian journalist Vlas Doroshevich was permitted to examine “the prison archive” on Sakhalin island, a collection of many convicts’ prison notebooks. Only after he had “earned the prison’s faith and complete trust” he wrote, was he allowed access. “A terrible lot of poems are written on Sakhalin,” he recorded in his travel notes, “immaculately handwritten and often with ornate illustrations drawn on the front pages [and are] archived as something very important, very valuable.”[3]

When Doroshevich asked one of the inmates, a man by the name of Lugovsky, why he wrote poetry, he was told, “when I lose heart, it’s my one consolation.” The prisoner, who did not trust himself with his own personal archive, had entrusted his best poems to a clerk for safekeeping. “I hid it from myself so I wouldn’t tear the notebook up during a drunk [sic]. During a drunk, I’m ready to destroy, tear up, or smash anything.”[4] One of his poems reads:

Regardless of deprivation,

Of the difficulty of heavy labors,

The villainous hard pitilessly oppresses

The people all the more.

I couldn’t endure . . . another moment . . .

I found a spare hour,

And in a moment of rage

Killed the guard out of sheer frustration.

So fell the victim of my revenge,

The blow was hard and true . . .

When word went round,

I confessed.

And there, friends, in a dark ward

I was sitting for six moths,

Languishing, as before, in dark thoughts

Unable to see God’s world.

Another prisoner’s poem, titled “Echoes of Hell,” in part described the desperate post-escape survival technique of cannibalism.

Many enter vagabondage

Having been lured by their comrades.

But when they fall asleep someone

Strikes them with eternal sleep.

They murder, and chop up the body,

Make a fire . . . and there’s kebabs . . .

They don’t remember him.

He’s not the only one who perished so.[5]

Illiteracy and prison study

Many 19th century Russian prisoners were illiterate and left no records at all. Yet, some untaught inmates sought literacy while incarcerated. Both of the two 19th century autobiographical monographs that describe the Russian katorga (hard labour) experience—Buried Alive by Feodor Dostoevsky, and In the Land of the Outcasts, by Phillip Iakubovich—emphasize that those in prison often turned to value writing in ways they may not have previously. In the prison described in Buried Alive (which Dostoevsky presents as the work of an exile, though the “thick pile of finely written manuscript”[6] is based on his own four years of confinement) writing materials are prohibited as well as all books aside from the Gospels. This environment, in which an absence of words pervades, seems to foster a craving for words in the inmates, for many who are incapable of signing their own names study the alphabet. In an endearing fashion, others suggest that they have more knowledge of the written word than might actually be the case. “I used to be able to write a little once; but I have forgotten now, since people have been writing with steel pens,” brags one.[7]

Iakobovich’s protagonist of Outcasts, Ivan Nikolaevich, is an educated political exile who undertakes a modest literacy campaign despite the prison’s ban on writing paper and pencils. He and his band of illiterate hard labourer-scholars use the grey paper, provided by the guards for cigarette rolling, as writing sheets. His students also hoard lists of letters that they attempt to memorize nightly. One, by the name of Pestrov, could hardly pronounce syllables when reading, yet “devoted every spare minute to studying; he’d sit on his sleeping platform[8] holding the alphabet I’d written and whisper to himself, exactly like a wizard doing the same with his incantations.”[9] Another inmate, Nikifor, would get up at night, after the guard had passed by the cell, and try to read and write by himself, “keenly listening for the guards footsteps, and, at each approach, dive into bed. Thus he sometimes sat up until daylight, without the slightest advantage in succeeding at his studies.”[10]

Yet, Iabokovich, who wrote In the World of the Outcasts as a memoir of the years he himself served in Siberian exile, remembers that despite their foibles when studying, “all [the prisoner students] cherished the dream of learning to write [. . .] Lord, with what suffering and diligence they scribbled on paper for entire days and nights; only you could hardly distinguish one letter from another.”[11] Those who desired to write letters to their wives came up against another obstacle: they had to create the missives in the orderly’s room where only ink was available as opposed to the bits of pencil and coal to which they had become accustomed. The same Nikifor, who studied at night while listened for the guard’s steps, declared after arduously writing to his wife that boring a hole (in a mine) seventeen inches deep was a far easier task than writing a letter, but nevertheless “sat tall and looked like a victor.”[12] Iukabovich notes that as time passed, the prisoner began to “unwittingly regard paper, pen, and book with respect, and the ideas attuned them to a higher tone and harmony,” such that eventually something “kind, blessed and warm” pervaded and edified the entire ward.[13]

Politicals in exile

During the 19th century political exiles were frequently exiled east of the Ural Mountains for opposition to the Tsar and hispolicies, or for having participated in populist, revolutionary movements such as the Narodnaya Volya, or People’s Will. Most of these individuals were highly literate, and had been guided to the revolutionary underground by their philosophical convictions. Many described the isolation of their exile experience in prison notebooks, which they also used as confessors, confidantes, and study logs. Although in general political prisoners constituted less than two percent of the Siberian exile population, they produced a large corpus of manuscripts while imprisoned.

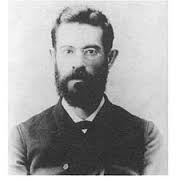

An example of this is Lev Shternberg, a political prisoner from Odessa. For serving as an editor of the revolutionary periodical

Vestnik Narodnoi Voli, (Herald of the People’s Will), Shternberg was arrested in 1886. He spent three years in an Odessan jail before boarding a transport ship to Sakhalin in order to serve a ten-year sentence. After his arrival, however, Shternberg alienated the island’s prison authorities, who subsequently assigned him to live in the isolated village of Viakhtu. Here the scholar’s loneliness caused him to turn to writing and study. Though separated from colleagues and libraries, he undertook a study the Gilyak, a group indigenous to the island. Shternberg later produced a three-volume ethnographic work on the social organization of the Gilyak, which was published after his death in the thirties.[14]

During his imprisonment in Odessa, Shternberg kept 14 prison notebooks. Some of his entries describe despair at his separation from society as well as reflections on his difficult childhood; other pages are exercises in foreign languages, such as French and Italian, or copied excerpts of the books he was reading, such as Robinson Crusoe, Shakespeare, and Milton.[15]

Lives in notebooks

Convict writing raises intriguing questions about authorship and intent. For what reasons did prisoners in exceedingly remote locations, many of whom had little facility with written language, go to such lengths to become literate or to leave written traces? Were they writing for themselves, to alleviate stress or boredom, or to simply pass the long years? Or, did they imagine that a future audience might find and read their words? Did the simple desire to not be forgotten underpin their efforts, or could the hope of “raising oneself to a higher station,” even if unacknowledged, cause the production of language and manuscripts in a way that free life did not? Was the need to have one’s sorrow acknowledged a guide for the convict writers?[16]

The authorial intentions behind 19th century prison writing remain for us, sadly, unknowable. All we do know is that the surviving body of prison writing indicates that prisoners seemed to cherish creating written records, regardless of their location or level of literacy. Wrote Doroshevich, on examining one of the prison notebooks of a Sakhalin prisoner, “there lay his entire life. Everything he saw and felt had been formed into consonances inside his head, often beggarly but always breathing sorrow and grief.”[17]

Notes:

[1] Vlas Doroshevich, Russia’s Penal Colony in the Far East. Trans. A. Gentes. Anthem: New York, 2011.

[2] Ibid p. 421-422

[3] Ibid p. 432

[4] Ibid p. 430

[5] qtd. in Doroshevich, p. 435

[6] Feodor Dostoevsky, Buried Alive: Or, Ten Years Penal Servitude in Siberia. Longmans Green and Company, 1881, p. 6

[7] Ibid p. 270.

[8] A bunk bed in a communal prison cell.

[9] Petr Filippovich Iabokovich, In the World of the Outcasts: Notes of a Former Penal Laborer, Volume 1. Ed. A. Gentes, New York: Anthem Press, p. 100.

[10] Ibid p. 103

[11] Ibid p. 107

[12] Ibid p. 109

[13] Ibid p. 108

[14] The Gilyak were renamed the Nivkh after 1917.

[15] Lev Iakovlevich Shternberg, The Social Organization of the Gilyak. Ed. Bruce Grant. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, 1999(82) p. xxiv-xxix. Shternberg’s notebooks are held today at the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg.

[16] As one of my professors once observed, “despite our best analyses, Richard Cory’s motivations remain as impenetrable to us as they must have been to those who found his body.”

[17] Doroshevich, p. 431

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

What an interesting and amazing find! The thought of them writing this poetry while imprisoned sends chills up my spine. I love history. So sad that Pashchenko was shot and only one volume was recovered. I imagine the full manuscripts from each of the prisoners were haunting.

I agree, if only more of such manuscripts has survived to the present day. In the World of the Outcasts treats this subject in great detail and is definitely a worthy read, especially as the whole volume was written by a prisoner. Thank you for your comment!

It certainly seems like a great read. I find clandestine writing to be exciting, as you know the prisoners’ true thoughts and struggles without any edits or varnishing of the truth. Thanks again for sharing. I had to come back to read it again. It’s rare to find something so raw and special. ~Gerri

~Gerri