In a previous blog, I wrote on the theme of the politics of comparison, of the connected history of circulation and mobility that underpins the CArchipelago project team’s approach to the historiography, theory and archive of penal colonies. Research associate Christian De Vito has since expanded the discussion, discussing the basis of various approaches to global history more generally, and suggesting ways that we might use them to enrich our historical analysis of the history of convict transportation (‘Comparisons & Connections.’) The generalised approaches that we have described are beguiling; they offer ways of making sense of the past, and of drawing out its relevance in a post-colonial world. But there remain real practical challenges for historians who wish to write connected, ‘crossed’ or comparative history. These challenges – of crossing place (travel), society (culture and language) and geographical or temporal spaces (expertise) – are in many ways the challenges of global history.

In the UK at least, team based approaches to the writing of history remain unusual. Though historians frequently meet, talk, discuss, present and peer review each other’s work, co-research and co-publication are far from the norm. Except in more social science oriented approaches – notably economic history, and large data gathering/ analysis projects – the stereotypical figure of the lone scholar to a large extent rings true. CArchipelago seeks to break new ground in this respect. We bring together a range of language skills (English, French, Spanish, Russian, Japanese) and expertise (labour history, history of punishment, subaltern studies, museum studies etc.), in order to write a different, more expansive kind of history than would be possible for any one of us, working alone. We lend our work coherence through our attention to what we call ‘comparative indicators.’ At a basic level, these speak to issues such as what kind of convicts went where, when and why; the nature of the penal and labour regime in different places; the significance of status, race and gender in shaping social and cultural hierarchies; the importance of individual and collective convict agency in defining experience; and the legacies of penal colonies in demography and heritage – the latter being the subject of previous blogs by myself (Bermuda), and Katy Roscoe and Eureka Henrich (Australia).

But as our work has progressed, the need for comparison has also draw our attention to the many crossings, or entanglements, of Empire, of the ways in which discussions and practices about and of convicts and penal colonies moved across imperial spaces. Here, I will give a short example of a current work-in-progress element of our work. One of our researchers, Takashi Miyamoto, who has previously blogged about Japanese prison tours in the British Indian Empire, has made a very careful study of late nineteenth-century penological journals published in Japan. These journals published many translations of the discussions about penal reform that were taking place at the time in the USA and Europe. Working together, and across our British, French and Russian sources, we have been able to locate what kind of work Japanese penologists were reading, and to trace how this influenced the nature and form of Japanese punishment – most especially the establishment of penal colonies in Hokkaido in the 1890s, and their devastating effect on the Indigenous Ainu, which Minako Sakata is examining in depth.

Another exciting avenue in our collective work has been research on convict escape. Indeed, Empires have a cartographic integrity and relevance that is challenged – forcefully – by convicts who moved illicitly and yet apparently seamlessly across political spaces. With respect to this theme, again we are working together across our contexts and sources; tracing convict experiences of evasion, piecing together complex narratives of inter-imperial responses, debates and disagreements, and foregrounding the deep political effects of their resistant mobility. In this way, as we trace Spanish convicts who crossed into British territory, British convicts who crossed into Spanish and French territory, French convicts who crossed into British and Dutch territory, and Russian convicts who escaped to Japan, we retain a focus on convict agency and experience, whilst through the often profound political effects of their evasion, we keep the global at the heart of our history of penal transportation.

This brings me to a wonderful week spent recently at the fabulous Archives Nationales d’Outre Mere, in Aix-En-Provence, the national repository for the archives of the French Empire. Extensive work with the excellent online catalogue, as well as lengthy consultations with one of our project advisors, Lorraine Paterson (Cornell), left us well prepared for a trip in which we sought to gather materials for one of the project case studies, on French Guiana. I say ‘us’ because in the spirit of the collaborative character of the project, I travelled with our project manager, Emma Battell Lowman, who like me reads and speaks French. The archives of French Guiana are vast, but before we left Leicester we had a very clear idea of what we were looking for: material on convicts that could draw out the intersections between the French and British Empires. Before we left, I had already read extensively accounts of French visits to Australian penal colonies, researched French participation in international meetings on prison reform, collected materials on French convict escapes into British territory, and worked on British campaigns against French Guiana – using material from the late eighteenth to mid-twentieth centuries. We decided to work on the first three of these themes, hoping in particular for further insights into French discussions on Australia and the French side of correspondence on convict escapes.

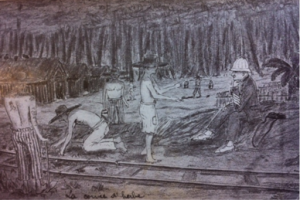

La corvée d’herbe [forced labour in the jungle]. René Belbenoit, Dry Guillotine: Fifteen Years among the Living Dead, illustrations by a fellow prisoner (New York, Blue Ribbon Books 1940).

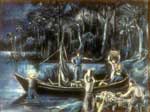

Francis LaGrange, A Well-Organised Escape on the Upper Maroni River, c. 1940-59.

It is difficult to convey in a short blog the richness of what we found. Archives included extensive nineteenth-century correspondence on British penal colonies in Australia (readers might like to consult Colin Forster’s wonderful book on this theme); and detailed accounts of convict evasion, including first-person convict accounts of how they left French Guiana, and many dozens of identification documents and convict photographs. Further still, and to our astonishment and delight, we found other kinds of records that will enable us to interrogate further penal colonies as spaces of imperial integration. Though we were familiar with the history of penal transportation from the French colonies of Algeria and Indochina to Guiana, we had not expected to find records of convict transportation from places like Madagascar and Guadeloupe. Resembling what we know to be true of the British imperial context (see my book Subaltern Lives), though to a degree that we are still trying to make sense of, African slaves and Indian indentured labourers were shipped to French Guiana as convicts, including for acts of resistance criminalised as, for example, arson on their masters’ estates. Here, we see the penal colony emerging as a site for the disciplining of unfree labour, as well as a site that created coerced labour. Both, of course, were inherently global in scope.

Readers might enjoy some of these resources:

http://www.archivesnationales.culture.gouv.fr/anom/fr/Action-culturelle/Dossiers-du-mois/1107-Evasions/Dossier-Evasions.html – online exhibition on convict escape, French Guiana

http://www.archivesnationales.culture.gouv.fr/anom/fr/Action-culturelle/Dossiers-du-mois/1004-Bagnes/Dossier-Bagnes-de-Guyane.html – online exhibition on the penal colony in French Guiana.

https://criminocorpus.org/en/ – a wonderful collection of resources and essays on French Guiana, as well as the history of punishment in France more generally, and the penal colony of New Caledonia.

http://digital.library.umsystem.edu/cgi/i/image/image-idx?page=index;c=devilic – paintings by C20th convict Francis LaGrange

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Recent Comments