The recent furore in France, over the wearing of Burkinis, has shone a new light on an age-old societal problem; the female body. Nowhere was the shock of a woman’s form greater than on the c18th and c19th anatomists’ slab.

The prospect of total exposure to the eyes of an uncaring crowd and the certainty of physical mutilation was a deeply unsettling prospect to both men and women of the era. Such scruples, were not simply concerned with avoiding being the object of ‘post-mortem porn’ but intimately connected to, however dimly understood, the importance of the integrity of the body in the prevailing Christian understanding of Resurrection and the possibility of life beyond the gallows. It is to such a case that I shall now turn.

On the morning of the 5th March, 1829, Newcastle’s Guildhall was full to bursting for the trial of Jane Jamieson, charged with the murder of her mother. Such was the public’s desire to witness the trial that many eager spectators were turned away. Amongst those unable to gain access was apprentice surgeon, Thomas Giordani Wright. His frustration at being denied a view of the proceedings was tempered slightly as, if Jamieson were found guilty, he would “most likely partake of the benefits accruing therefrom.” The benefits of which Wright spoke were, of course, the use of Jamieson’s body for dissection.

Under the terms of the 1752 Murder Act, Jamieson was found guilty and sentenced to be hung and then anatomised by Newcastle’s Barber Surgeons. In one fell swoop she became both the first woman hung on Newcastle’s Town Moor since 1758 and the last. However, it was her anatomisation that proved the most shocking element for herself and the wider public, dissection of a woman being remarkably rare owing to the low execution rates.

The anatomist’s slab was foremost in Jamieson’s thoughts. As with so many before her, she feared the surgeon’s knife more than the hangman’s noose. In her final moments on the morning of her execution, she asked the attendant Reverend Green a “question about her body.” The Reverend suggested she was “not to care about her body but about her soul.” She was not alone in placing the dread of dissection over the fear of hanging, as one ballad of the time makes clear.

“O pity my unhappy state,

And now take warning by my fate,

My lifeless body must be torn

By sad dissection’ss dreadful arm.”

Lamentation of Jane Jamieson, who was executed at Newcastle, on Saturday, the 7th day of March, 1829, for the murder of her own mother

http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/view/edition/7162

Jamieson’s case is remarkable for several reasons, but chief amongst them is the detail in which it is recorded. Thanks to a chance discovery in 1985 in a house in Nanaimo, British Columbia, Jamieson’s dissection is one of the very few, in much of the North East in this period, for which we have any sort of detailed record.

The record in question is the diary of the aforementioned apprentice surgeon Giordani Wright. Wright was apprenticed to one Mr McIntyre of Newcastle between 1824-1829 and kept a near daily diary, which gives a fascinating insight into local medical practice in the early c19th; not least post-execution dissection.

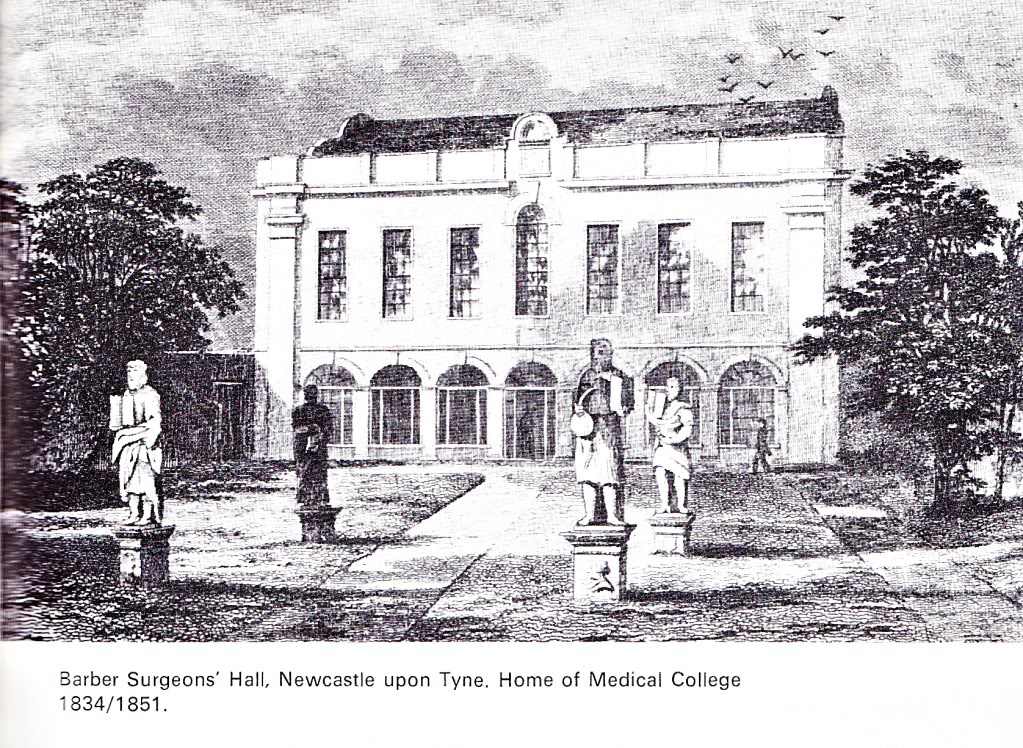

Dissections and their attendant lectures took place at Newcastle’s Barber Surgeon’s Hall. The Hall was just a stone’s throw from Carliol Street Gaol, completed the year of Jamieson’s execution and where she spent her last hours. It is first described in the early 1700’s in the marvellously titled Through England on a Side Saddle. The author, Celia Fiennes, details a dissection room with a round table at its centre and seats and benches railed round for the convenience of spectators. She also noted the presence of two anatomised bodies, one of whose bones had been fastened with wires and another whose flesh had been boiled off. Both of these are reported in a remarkably matter of fact manner for a sight that we as historians so often believe to have been deeply troubling to the general populace in the period. The building itself was later rebuilt in 1730, and according to a local historian of the time was a stylistic triumph but rather, “too great an ornament for such a dirty part of the town.” It was in this “great ornament” that Wright witnessed the dissection of Jamieson.

According to Wright, Jamieson’s body was used for instruction in a series of lectures that ran for just under two weeks, the first of which took place the Monday following her execution. The series was free to surgeons and open to the public on payment of half a crown per lecture or half a guinea for the full course. Records show that the fees were to cover the costs of the lectures and any additional profits were to go to the local Eye Infirmary. Wright gives a fascinating insight into the intended audience of these lectures. Of the few he attended, he found they offered very little information as anatomical lectures. Instead, he thought them far more appealing to the “tyros of the profession” and a more “general audience.”

Wright was not entirely dismissive of the lectures. Indeed, in one lecture on Jamieson’s brain, he noted how the freshness of the specimen allowed for far clearer instruction than was often the case. Newcastle’s surgeons were victim to the same shortage of bodies that hindered anatomical instruction up and down the country and Newcastle itself was no less immune to the attendant nefarious practices that so often accompanied such a shortage. Writing just two months before Jamieson’s trial the Newcastle Courant noted, of resurrectionists, “So much does every person…fear such men, that after dark everyone you meet in any bye place is sure to be taken for a resurrection-man.” These popular fears weren’t helped by medical men, like Wright, who relished the thought of his body terrifying others. In one entry he remarked, “I can indeed contemplate with perfect satisfaction the idea of being stuck in a glass case – the terror of young ladies and little boys – the admiration and study of professors.”

Patrick Low is an expert in the history of execution in the North-East of Britain. His research blog, http://wwww.lastdyingwords.wordpress.com/, is a must read (seriously, go now and read) and Patrick will shortly be completing his PhD at Sunderland University.

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

[…] It’s not strictly Canadian history, but the chance discovery of the dissection of Jane Jamieson in Nanaimo, BC in 1985 has allowed for the s…. […]