A few weeks ago the Carceral Archipelago team of postgraduates presented at the University of Leicester’s annual postgraduate conference. The theme of the Carceral Archipelago panel was “Convicts, Indigenous People and Labour”. The project’s three postgraduate students – Kellie Moss, Katy Roscoe and Carrie Crockett – presented three papers that ranged from Western Australia to the Aleutian Islands.

Kellie Moss spoke about the varied strategies Western Australia used to try and build a labour force capable of sustaining the colony between its establishment in 1828 and the arrival of convicts in 1849. She placed the decision to transport convicts into Western Australia within a longer history of labour exploitation of a number of different groups, including indentured servants, Aboriginal labourers and juvenile delinquents sent from Parkhurst Reformatory to work as apprentices at Swan River. This multifarious labour force blurs the boundaries between free and unfree labour. Frequently, the arrival of convicts is heralded as the arrival of unfree labour to the shores of Western Australia, but in fact coerced labour emerges as a key context of convict transportation policy. The limitations of using other forms of coerced labour – in particular the short terms of their contracts and their dispersed nature – eventually resulted in a preference for large scale convict transportation, who could be administered centrally and whose terms of sentence were longer. The first two decades of Western Australia’s history is relatively unexplored in existing scholarship but it is key to understanding the subsequent arrival of 10,000 convicts to Western Australia between 1850 and 1868.

This image shows the colony in its early years, with some farmed land and buildings, but in need of large scale infrastructure that convicts would ultimately provide.

Panorama of the Swan River Colony, by Eliza Jane Currie (1831), State Library of New South Wales.

Katy Roscoe talked about the role of Aboriginal prisoners as a labour force before and after the arrival of convicts in Western Australia from elsewhere in the British Empire. Rottnest Island was established as a prison in 1839 with the intention of training Aboriginal convicts in the skills of farming and the importance of discipline in order to become “useful to settlers” upon their release. The arrival of convict ships from Western Australia in 1850 shifted the focus towards labour as punishment, rather than labour as training. This resulted in Aboriginal convicts being incorporated into road gangs, building the roads to Albany and the public school at Perth. However, having Aboriginal convicts labouring on the mainland became unpopular with the public due to large numbers of escapes and the unpopularity of chains in the post-slavery era. As a result, Aboriginal prisoners were returned to Rottnest Island. As the restricted space on the island limited the utility of arable land, convicts were sent individually and in small groups to work for settlers or government departments, as pearl divers, trackers, mail couriers, telegraph operators and police constables. This shows how the Aboriginal convict labour force converged with wider penal policy, before diverging because of a perceived “threat” in the form of escaped convicts. It further suggests that despite the expectation that a prison island would be isolated, the drive to make convict labour useful resulted in a flexible and mobile labour force that contributed to the infrastructure and running of the wider colony.

The use of Aboriginal prisoners as trackers often resulted in bizarre situations in which they were escorting fellow prisoners or tracking down escaped convicts.

Aboriginal Prisoners in chains, posed with a policeman and Aboriginal trackers (1890), 7816B, State Library of Western Australia

Carrie Crockett discussed the unique Native-Russian cultural hybrid that resulted from fur-driven Russian colonization into the Aleutian Islands during the 17-19th. Instead of the Aleuts becoming marginalized by Russian concerns, and in juxtaposition to some academic scholarship on the subject, archival research reveals that the society that resulted was one in which both Native groups and Russian groups often flourished together. Carrie theorized that the character of the Russian colonists might have contributed to this result, as most of them were either of Native Siberian-Russian ancestry, or were exiles who had been sent to live east of the Urals–without provision for return–from European Russia. Carrie’s paper skilfully explored the complicated dynamics that underlay interactions between two groups that are frequently labelled as “marginal”. In many contexts the exiles and ex-convicts who made up the Promshleniki would be labelled “marginalised”, and to a greater extent so would the Indigenous Aleuts. However the interaction between the two in the procurement of otter pelts and seal skin demonstrates a mutually profitable business relationship between “marginalised people” that formed part of a lucrative global economy.

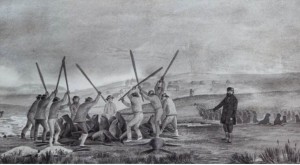

Russian Promyshlennik supervising Aleut hunters clubbing seals. The ranks of the Promyshlenniki included St Petersburg nobility, Siberian merchant families, assigned political exiles and criminals who had escaped from Siberian prisons.

The three papers presented by Kellie Moss, Katy Roscoe and Carrie Crockett demonstrated the highly distinctive character of Indigenous, convict and labour relations in different contexts. All papers demonstrated the flexibility of categories such as free and unfree labour and people considered to be marginalised. The papers also pointed to the ways in which even coerced labour fostered mobility, both regionally and across empire.

Subscribe to Katy Roscoe's posts

Subscribe to Katy Roscoe's posts

Recent Comments