One of the wonderful things about ‘blue skies’ research is the element of surprise that it can throw up. When I began work on ‘The Carceral Archipelago’ project, I had not planned to work on the British Caribbean. I had long been aware of early-modern British and Irish convict flows to islands like Barbados, and from the turn of the nineteenth century, convict transportation from Britain’s West Indian possessions to the Australian colonies. However, five years ago I knew nothing of debates about or the existence of penal settlements and colonies in the British Caribbean, and only recently have I come to understand their importance for Britain’s Atlantic world. This blog tells the story of one such place: Her Majesty’s Penal Settlement (HMPS) Mazaruni. It was established in British Guiana in 1842, remained open until 1930-9 when it closed briefly, reopened in 1940, and changed its name to Mazaruni Prison in 1950. Since Guyana’s independence in 1966 it has remained in use as a jail.

The prison ship in Bartica.

I started to work on British Guiana because of my interest in the escape of French convicts into British jurisdictions in the Caribbean and Pacific. Calling up various archival indexes and files, my eyes were immediately drawn not just to the testimonies of escaped convicts, and the diplomatic wrangling that they instigated, but to the mention of a kind of prison that I had not encountered before: not a ‘Prison’, ‘Gaol’, or ‘Jail’, but a ‘Penal Settlement’, located far upriver from the capital of Georgetown. In my work on British Asia, I have routinely used the term ‘penal settlement’ to describe sites of overseas convict transportation in places like Mauritius, Singapore or the Tenasserim Provinces of Burma. The term is suggestive, I think, of the shipment of convicts to already colonized territories. This is distinct from the use of convicts as a means for the occupation of land represented as terra nullius (nobody’s land), as in the Australian colonies or the Andaman Islands, which I call ‘penal colonies’. But, until I learned of the history of Mazaruni, I do not recall having ever seen the phrase ‘penal settlement’ being used by contemporaries in the official naming of carceral sites. Though I have been unable to locate the genealogy of the nineteenth-century use of the term in the British Caribbean, it seems to imply a relatively open penal location in a remote place within the colony of conviction.

The view of Mazaruni from the Parika to Bartica speedboat.

Last year I dedicated a great deal of time to piecing together the history of HMPS Mazaruni, using various archives in London, Edinburgh and Aix-en-Provence. I wanted to make sense of its significance both for the British governance of colonial Guiana and a larger imperial and global history of penal colonies. Then, through a serendipitous connection, via my membership of a Leicester-based British Academy funded UK/ Caribbean network that connects scholars of crime and punishment, University of Guyana (UG) historian Dr Mellissa Ifill extended an invitation to visit the country. And so last month, I found myself on a flight to the Caribbean.

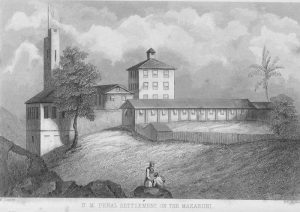

‘Oldest prison block’. Undated (19th century).

It was Governor Henry Light who established Mazaruni. He had been appointed to British Guiana in the year of the final emancipation of enslaved people (1838). He initially envisaged Mazaruni as a place for the reception of British convicts. He put forward his plans at the same time as anti-transportation rhetoric was gathering force in Britain and the Australian colonies, protesting against the continuing shipment of convicts to the Antipodes. The Court of Policy (Guiana’s legislative body) refused to accept Light’s proposals, though, and his plans went to ground. A couple of years later, he came up with an alternative idea: the establishment of a penal settlement for locally convicted prisoners. The Court of Policy was more enthusiastic, and building works began, initially by free labourers and later by convicts. Started at the end of 1841, the penal settlement opened in 1842, and the final stones in this first phase of development were laid in 1845. Though other British possessions in the Caribbean made repeated requests to send convicts to Mazaruni, Guiana always refused them, and the settlement only received convicts from within the colony itself. A second phase of construction came later in the 1870s, and included the building of a wall around the jail structures.

Light believed that Mazaruni was an ideal site for prisoner rehabilitation. Removed from the supposed bad influences of Georgetown, and taken to this extremely isolated spot, he believed that convicts could be kept apart from their peers, punished through work, and reformed through religious reflection, basic education and the learning of work skills that would prepare them for release. At the same time, Light believed that the penal settlement would open up better communications with Georgetown, and so catalyse settlement and development in the colony’s interior. Moreover, Mazaruni was close to a plentiful supply of granite. From the very first years, convicts were employed as hard labour in its extraction, with the stones taken upriver to the capital and used to pave the streets and build the seawall defences (much of Guyana is below sea level). This combination – of punishment, reform, labour and resource extraction – was characteristic of penal settlements and colonies all over the British imperial world, and Mazaruni was no exception.

The settlement was, however, from the earliest years, rocked by scandal. Though its isolated location seemed to render it an ideal carceral site, it also made it difficult to supervise overseers and warders. There were allegations of short rations, the overwork and ill treatment of prisoners, and horrific incidents of violence. These included one case in the second half of the nineteenth century when the governor issued a warrant for the arrest of a British medical officer, who had fled to England following neglect and cruelty of such magnitude that several inmates had died under his charge. But the prison remained in use, though the number of inmates gradually decreased over time – from a daily average of almost 250 in 1846 to around 100 in 1943, when it was the second largest jail in the colony, after Georgetown. This is still true in Guyana today.

During my visit to Guyana, the Ministry of Public Security (which oversees the Prison Service) and the University co-sponsored my delivery of a public lecture on Mazaruni Prison in the capital, Georgetown; which I gave to a room full of prison officers, prison cadets, university faculty, and other interested parties. The Honourable Minister Mr Ramjattan, Vice-Chancellor Professor Griffith, and Head of History Ms Estherine Adams presided. The audience’s engagement with the history of Mazaruni genuinely took me aback. As we discussed some of the issues that my talk had raised, the audience told me two things. The first was that many of the nineteenth-century jail structures that I had shown in historic pictures and photographs still stand today. Second, the problem of how best to manage the prison today resonates profoundly with debates that took place some 170 years ago. What is the best use for this peculiarly situated and isolated prison site? How best should we balance punitive measures with rehabilitation? What kind of work could or should prisoners do? What are the alternatives to imprisonment? Are jails attractive to those in desperate poverty, rather than a deterrent against crime?

Just one week later, following a fascinating visit to the country’s female prison in New Amsterdam, and a wonderful stint in the prison history collections of Guyana’s National Archives, in a trip organised by acting director of the Prison Service Mr Samuels, and accompanied by chief officer of Georgetown Jail Mr Pilgrim, official photographer Mr James, and Dr Charleen Wilkinson of UG, I set out for Mazaruni Prison itself.

The now disused bathing pool.

Though not an island, Mazaruni is located on a littoral of the western shore just south of where the great Mazaruni River flows into the Essequibo. From the river, the site looks like an island (many Guyanese today are surprised when they are told that it is not an island), and it is only possible to reach it from the water (there is no road.) Visitors travel either on one of the large, slow steamboats that plies the waters from Georgetown, or like us drive to Parika, and take a one hour speedboat ride from there. In parts, the river is 15 miles wide. The stopping point from Parika is Bartica, on the opposite shore to Mazaruni, and from there the prison service ship takes passengers on the short hop across the water.

The author recording audio for the use of the prison service.

Historically, from the early nineteenth century, the town of Bartica was the site of a mission station. Just north of Mazaruni is Kaow Island, which was once a leper colony. For this reason, I think of its general location as a ‘carceral junction’. Today, Bartica is a thriving place, though Kaow Island lies in ruins. Mazaruni is still a working jail, and incorporates prisoner barracks, cells, workshops, refectory, boundary walls and an exercise yard; as well as staff offices, accommodation and an officers’ club. There is a ruined chapel, clock tower, colonial-era graveyards (one for officers, one for prisoners), a disused seawater bathing pool and flat grounds once levelled for tennis courts. The prison faces onto the water, and thick jungles border it to the rear. Beyond the prison buildings is a working farm, where inmates grow vegetables and rear pigs for consumption in the jail. The site is huge – over 6 acres – relatively open, and in parts the ground is rough. From one of the high points of the settlement it is possible to see the new luxury resort of Banganara, downriver to the south.

One of the vegetable gardens on the prison farm.

It is difficult to describe the intensity of the experience of walking the grounds of a place that one has researched for so many months. I have, of course, in the past 20 years researched and visited numerous penal settlement and colony sites, often repeatedly: for instance in the Andaman Islands, Australia, Bermuda, Japan and Singapore. As a graduate student in the mid-1990s, I lived for a year in Mauritius, returning for a further 6 months in 2004. In each of these locations, there is to a greater or lesser degree some form of memorialisation, commemoration, or convict-related heritage. Indeed, the way in which convict history is remembered has been one of the key concerns of researchers on ‘The Carceral Archipelago’ project, and we have blogged about this theme on these pages.

Prisoners going to bathe, Illustrated London News, 1888

Warders’ cottages. Undated.

Postcard. Undated.

The prison buildings. Undated (19th century).

However, to visit a former British penal settlement, still a working jail with so many historic resonances: this was something entirely new to me, and entirely different to my past experiences. A staggering number of the original structures still stand, in some cases in ruins (the chapel) or repurposed (cellular accommodation). There are several plaques noting dates of construction (e.g. on the clock tower). Moreover, Mazaruni Prison has retained its character as a semi-open penal settlement rather than a closed prison, in which inmates work outdoors by day, and are confined in their wards at night. And so, for the first time, I felt like the research that I have been doing on penal settlements and colonies has the potential not just to provide an historical background to contemporary debates about incarceration, but to actively connect history and the present, and in so doing to make an important intervention in current policy debates.

The ruined chapel.

The clocktower.

For example, in the 1850s as also today, government administrators and jail officers were/are keen to know how best to employ inmates, how to render jails more self-sufficient and productive, and how to cut re-offending rates. Knowledge of what has been piloted or implemented in the past can help inform these debates. For instance, with respect to the prison farm of Mazaruni specifically, how to train inmates in agriculture? Which crops grow best in Mazaruni soil? What kind of rotation works? How much livestock can it sustain? These are concerns that preoccupy Guyana’s prison service as much as they did the colonial administration of British Guiana. Could past experience deliver relevant knowledge now? This is a concern that, in partnership with my new colleagues at the University of Guyana and in the Guyana Prison Service, I will continue to explore in the coming months.

For their generous hospitality in Guyana, I would like to thank Dr Mellissa Ifill, Maiya Francois-Ifill, Marcia Ifill, Myrna Ifill, Karen de Souza, the Honourable Minister Ramjattan, Vice-Chancellor Professor Griffith, Deputy Vice-Chancellor Dr Scott, Estherine Adams, the staff at the Sir Walter Rodney Archives, photographer Mr James, and Mr Samuels, Mr Pilgrim, Ms Cox and Mr Hopkinson of the Guyana Prison Service. I also thank the prison warders who showed us around New Amsterdam and Mazaruni, and answered our many questions, and the inmates of Mazaruni who cut our path to a remote area of the site.

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

I enjoyed your research on the Mazaruni prison.

I went there in late 1980’s. I was part of an expedition called “operation Raleigh”

We were supposed to do a community project at the jail, but was deemed too dangerous.

I did repair their boats outboard and have drinks in the officers mess.

It still strikes me today, the worn out uniforms and shoes of the prison officers, but their attempts to continue to run the prison as the British had done.

It was a freightening place!

Thankyou for this interesting article. My Great Grandfather worked @ Mazaruni penal settlement. We have family stories passed down from him about his experiences. Do you know if there is any historic staff records available?

That’s so interesting! Most of the Mazaruni records are in the UK National Archives at Kew. There would surely be some trace of him in those, but it would require quite a bit of digging.

Really informative