By Kellie Moss

Fremantle Prison, Western Australia (authors own image).

The history of convict confinement in Western Australia has been dominated by one towering limestone structure: Fremantle prison. However, convicts were incredibly mobile as they built public works beyond the walls of the prison, and received nominal freedom as probationers and ticket-of-leave holders. In this blog, I assess the multiple functions of the regional convict depots which acted as places of reintegration and control.

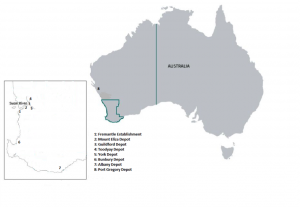

9,925 male convicts were sent to Western Australia between the years 1850-1868, after a successful campaign by the colonists to convert Australia’s first free settlement into a penal colony. (1) The growing movement towards the abolition of transportation to New South Wales and Tasmania in the 1840s placed Western Australia in a unique position to dictate the terms of the convict system they hoped to implement. In a bid to alleviate their labour deficiency the colony requested young male convicts, who were primarily from rural backgrounds, and had already completed most of the penal phase of their sentence back in England. To ensure public works were completed across the colony a regional hiring depot scheme was introduced. Thus, regional convict depots were set-up in the towns of Albany, Bunbury, York, Toodyay, Lynton (Port Gregory), Geraldton and Guildford.

Map of Regional Convict Depots in Western Australia.

These depots were usually located within or close to towns and served as a base for the local administration of the convicts. After demonstrating good behaviour, a ticket-of leave was issued to probationers after a specified period had been spent labouring on public works. Following their discharge the men were free to select an employer and the region they wished to work in. Upon selecting their employer ticket holders were then bound to the restrictions of the Master and Servants act. If a ticket-of-leaver could not find private employment they remained at the hiring depot to work with the probationers in road parties. Adherence to the rules by the convicts ensured their progression through varying stages to freedom, whilst misconduct saw them return to a lower stage, or even to Fremantle prison.

The depot system ensured the convicts were evenly distributed rather than concentrated in one area, ensuring that settlers on the peripheries of the colony had access to this vital source of labour. This in turn ensured high rates of employment for the ticket of leave holders, helping to ease their transition from bond to free society. The need for labourers not only ensured that their past crimes were overlooked, but that they were welcomed by the colonists. (2) This welcome not only extended to their employment, but also the formation of relationships with free settlers. It is difficult to gauge how many of the convicts went on to marry, as those with conditional pardons or certificates of freedom did not need to request permission to do so. However, records for ticket holders are more readily available. On average around 20 ticket-of-leavers requested permission to marry each year, between the years 1852-1860. Though this only amounts to 2% of the ticket of leave population, given the imbalance of the sexes within the colony, and the lack of single marriageable women, it demonstrates the willingness of the colonists to accept these men into their community. Furthermore, during the years 1850-1860, another 10 ticket-of-leavers on average per year made applications for their wives and families to join them in Western Australia. A move which the British and colonial government made financially possible to ensure the continued good behaviour and settlement of ticket holders in the colony after their term expired.

As well as encouraging the integration of convicts into society the regional depot system was recognised as a viable method for a colony with limited means to manage the men. The spatial characteristic of the hiring depots meant the system relied heavily on the convicts to adhere to a strict set of regulations designed to ensure the men’s mobility, labour and control. (3) These included always carrying their ticket of leave, being indoors after 10.00pm, and refraining from drinking alcohol. Ticket holders were also required to report to the resident magistrate bi-annually, reflecting the determination of the convict system to control their location. The threat that any breach of the rules would incur a loss of their ticket, and a return to Fremantle prison remained the key incentive in ensuring their adherence to the regulations. (4)

However, whilst the depots provided the ticket-of-leave men with the opportunity to become part of the communities in which they worked, for many the process of integration remained elusive. A fact which is highlighted by the high number of ticket-of-leavers who went on to commit minor crimes after their sentence had expired. Although, a high number of these offences appear to be due to the stringency with which breaches of regulations were enforced. (5) The system of awarding gratuities to the convicts on their release from public works was another factor in the high rate of reconvictions as the money was frequently used to purchase alcohol. (6) Offences deemed more serious, such as minor larcenies, assault and absconding from service remained relatively low. Therefore, the acceptance and control of the convicts appears to have been limited to those deemed ‘useful’ by the colonists.

In an attempt to further regulate the ticket-of-leave holders and ensure they remained in their designated districts additional forms of control were also enacted by the colonial government. In 1851 police officers were recruited to combat the problems created by the ticket holders in the main districts, connecting the extension of settled areas to the ticket of leave system. The pensioners guard (retired veterans) was a resource utilised in the control of the convicts during their transportation to the colony, and retained to quell any future uprisings. The depots therefore performed another function housing the pensioner guards and the local police force in small villages to ensure they were on hand if needed. Whilst these forces of coercion were created to provide protection for the settlers from the colony’s increasing convict population, they were also frequently utilised in the control of the indigenous population.

The Aboriginal peoples remained a source of concern for many colonists in Western Australia as early attempts to educate and use the Aboriginal population as a labour force had proved unsuccessful. Although incidents involving the indigenous population were rarely experienced within the more established areas of the colony by 1850, settlers living on the outskirts of the colony remained fearful of their presence. The increased number of labourers that the ticket of leave system brought dramatically increased the leasing of Aboriginal land to European pastoralists leading to the dispossession of whole populations of indigenous peoples. By establishing hiring depots at the far reaches of the colony the colonial government were not only ensuring access to a continual supply of labourers, they were also making known and securing the colonial spaces of Western Australia.

1: http://www.sro.wa.gov.au/archive-collection/collection/convict-records

2: HCPP, Convict discipline and transportation. Further correspondence on the subject of convict discipline and transportation 1851, (1361, 1418), Vol. 45. Copy of a despatch from Governor Fitzgerald to Earl Grey, July 17, 1850, pg. 221

3: Trinca, Mathew. The control and coercion of convicts: in Building a Colony: The Convict Legacy. Sherriff, Jacqui and Brake, Anne (eds.) Studies in Western Australian History, No. 24, 2006: 26-36.

4: HCPP, Convict discipline and transportation. Further correspondence on the subject of convict discipline and transportation, 1851, (1361 1418), Vol.45, Enclosure from Comptroller General’s Office, July 1850, pg. 232

5: HCPP, Convict discipline and transportation. Further correspondence on the subject of convict discipline and transportation, 1862, (2981), Vol.45, Enclosure from Comptroller General’s Office, January 31st 1862, pg. 35

6: HCPP, Annual Reports on Convict Establishments at W. Australia and Tasmania 1867, (3851), Vol.49, Enclosure from Comptroller General’s Office, January 31st 1867, pg. 5

Kellie Moss is a PhD candidate in the School of History, Politics and IR, University of Leicester.

Subscribe to abarker's posts

Subscribe to abarker's posts

Recent Comments