A few years ago, the eminent scholar of the Russian Gulag, Professor Judith Pallot, challenged me to consider the relevance of the sociology of incarceration as a means of understanding convict experiences in penal colonies. She advised me to think in particular about Gresham M. Sykes’ classic 1958 text, The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison. In this blog I will consider whether Sykes’ work on ‘the pains of imprisonment’ in the mid-twentieth century is a useful means of thinking about how – historically – convicts experienced penal transportation and/ or penal settlements and colonies. Can we detect historical patterns, or distinct changes over time towards these pains? Have they always featured in historical forms of carceral mobility and confinement? Or did they not feature at all?

Sykes’ analysis was grounded in research in the New Jersey State Prison. He argued that although ‘modern’ prisons had displaced past practices of bodily suffering as punishment, prisoners in penitentiaries still experienced equivalent pain. ‘The inmates are agreed,’ he wrote, ‘that life in the maximum security prison is depriving or frustrating in the extreme.’ These deprivations and frustrations, he went on, threatened inmates psychologically in profound ways.

New Jersey State Prison (http://www.prisonpro.com/content/new-jersey-state-prison)

Sykes detailed the ‘pains of imprisonment’ as follows.

First comes ‘the deprivation of liberty’, through confinement in an institution cut off from family and kin. Over time, he noted, prisoners lose their connection to free society outside the prison walls, and become lonely and bored. Their ego is threatened both by their moral rejection from legitimate society and by the many forms of degradation that incarceration produces (shaving of head, wearing of uniform, issuing of a number instead of a name etc.)

Second is ‘the deprivation of goods and services’. Prisoners do not have the right of ownership (even of a blanket), and despite the fact that their basic needs are met they are forced to live in what Sykes describes as ‘a harshly Spartan environment which they define as painfully depriving.’ Because of the social value attached to the ownership of material possessions in modern culture, this represents an attack ‘at the deepest layers of personality’.

‘The deprivation of heterosexual relationships’ is the third of Sykes’ pains of imprisonment. This ‘involuntary celibacy’ represents, he argues, a figurative castration, which is both physically and psychologically serious.

Next, we come to ‘the deprivation of autonomy’. This means the ways in which inmates are denied self-determination, or the ability to make choices, with respect for instance to when they eat and sleep, or the work that they do. Prisoners, Sykes argues, feel this as ‘irritating, pointless gesture[s] of authoritarianism.’ This is augmented by the prison authorities’ deliberate withholding of information and refusal to explain their decisions.

The final of Skyes’ ‘deprivations’ is that of ‘security’. By this he means the infliction of ‘prolonged intimacy’ with violent and aggressive men: ‘… the constant companionship of thieves, rapists, murderers … is far from reassuring.’ They are also at risk of sexual abuse. All of this makes inmates acutely anxious, because the need to stand up to threats against them is a test of their ‘manhood.’

To what extent are Sykes’ insights relevant to understanding the experience of penal confinement historically? And do they help us to generate a convict perspective on transportation or penal colonies?

During the early modern period (to roughly speaking the last quarter of the eighteenth century) many European convicts travelled and worked with other coerced labourers – including in the British, Spanish, Portuguese and Danish empires impressed soldiers, enslaved Africans and Asians, and European indentured servants. Their destinations, including military forts and plantations, did not spatially confine them in the way that the built structures of prisons did. There was plenty of opportunity for them to mingle with other workers, and neighbouring migrants or settlers. Nevertheless, the families of convicts did not usually accompany them (though in some contexts a few were co-convicted, or followed them), and they suffered considerable degradations as they journeyed into transportation. This degradation continued into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and could include lengthy forced marches to port (Russia), confinement beneath ship decks (most who went by sea routes), and subjection to particular shipboard routines including enforced ‘exercise’ or common messing (British India). There is an argument that convicts’ voyages created particular forms of sociability and a commonality of experience that produced separate identity forms, like Indian bhais (brothers), or the ‘shipmates’ of the Australian colonies. Further, and significantly with respect to our examination of ‘loss of liberty’, convicts had little choice in their onward mobility – for they were often moved around from place to place from their initial destination, according to labour or other desires (Spanish Empire, Straits Settlements).

Later on, in the nineteenth century, all over the world, including in post-independence Latin America, the American Philippines as well as the French colonies of Guiana and New Caledonia, places designated as ‘penal settlements’ or ‘penal colonies’ developed, incorporating barracks and prisons as well as more open villages and settlements. Here, convicts were made to wear uniforms, be fingerprinted and anthropometrically measured, have their heads shaved, and appear at regular head counts, or musters. In each of these respects, they had more in common with Sykes’ prisoners than did earlier convict flows. However, they still enjoyed more freedom of movement than prison inmates, as they travelled daily from their barracks, cells or huts to work, to a degree that often surprised visitors from outside.

The Anthropometry Studio, St-Laurent-du-Maroni, French Guiana. Photographs: Clare Anderson (2015)

‘The deprivation of goods and services’ is interesting, for in the contexts that I have been exploring (even in the twentieth century), many convicts were both allowed and actively encouraged to have possessions. This could range from ‘bundles’ that they took into transportation with them, to the ownership of livestock (Bencoolen, Andamans). The key point here seems to be the near-constant shortage of funds for convict shipment and maintenance, and the desire to reduce the cost of transportation and/or penal colonies. In effect, this meant that numerous regimes encouraged the kind of (convict) entrepreneurialism that scholars have previously shown were a feature of slave societies. Convicts in numerous contexts – from Bermuda to French Guiana, Russia and Japan – engaged in the manufacture of crafts, as well as bartering and trade. This in turn was strongly related to the absence of the total deprivation of liberty discussed above – though note that officials and guards routinely confiscated or demanded bribes to turn a blind eye to convict possession of forbidden articles (notably stimulants like opium, liquor etc.)

Top: Toothpick holder, made by a convict, c. 1881-1926. Left: In 1909, prison pharmacist Tanabe arranged to give umeboshi (pickled plums) to a sick prisoner. He was deeply moved and made this rosary with the plums’ seeds to give to Tanabe as an expression of his grateful feelings, c. 1909. Tsukigata Kabato Museum, Hokkaido, Japan. Photograph: Clare Anderson (2015). Translations: Minako Sakata.

Left to Right: Mini Shamisen (musical instrument), Mini Geta (shoes), Mini Waraji (sandals) and Mini Bottle Gourd. Products made by convicts of the Kabato Shuchikan Prison. Tsukigata Kabato Museum, Hokkaido, Japan. Photograph: Clare Anderson (2015). Translations: Minako Sakata.

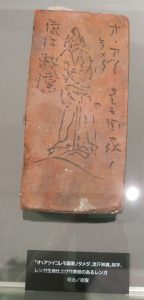

Convict inscribed brick. Left: ‘A profuse perspiration’. Right: ‘Oh it’s hot, but this is for the sake of our country’, c. 1881-1912 (replica). Abashiri Prison Museum, Hokkaido, Japan. Photograph: Clare Anderson (2015). Translations: Minako Sakata.

It is difficult to access the history of sexuality in archives, particularly of marginalised peoples such as convicts. What we do know, with respect to Skyes’ ideas about the deprivation of heterosexual relationships, is that in many contexts, convict flows and penal settlements and colonies were overwhelmingly homosocial. However, in contrast to the confinement of male and female prisoners in separate institutions, convict men and women were not always kept apart. Indeed, there was a close relationship between penal transportation and the desire to colonize, or settle, the frontiers of states and empires (Russian Far East, littoral Bay of Bengal). In this respect, the authorities often actively encouraged the importation of convict women, or free women, of convicts’ wives, mothers and children (Andamans, French Guiana), though not always with success. Of course, same-sex intimacy was a feature of convict settlement, and convicts forged loving relationships with each other – as well as those of claimed abuse, which more commonly feature in archives of regulation and investigation.

It is in the deprivation of autonomy and security – as well as the degradations mentioned above – that perhaps historic experience resonates most closely with contemporary imprisonment. Indeed, the former (loss of autonomy) might be seen as an early expression of what Michel Foucault later described in his detailed accounts of the routines and rhythms of hospitals, jails, and schools. There are also resonances with Erving Goffman’s description of ‘total institutions’ a decade later. For all that convicts enjoyed relative freedom of movement and sociability, most were subject to regimes of life and work in which they had limited choice. We must recognise this, even as we recognise the contemporary legacies of convicts’ remarkable creativity in global transformations – including via the clearing of land, and the building of forts, villages, towns and dockyards – and their impacts on neighbouring free and Indigenous communities. It is also clear that sub-cultures in penal settlements and colonies developed, in which some convicts colluded with each other, and with soldiers and guards, at the expense of the safety of others. This could include the trafficking of food, alcohol and tobacco; and the exchange of money, provisions or sexual favours for the removal of fetters or the enforcement of light work. Violence lay at the heart of convict transportation, and was embedded in the operation and everyday culture of penal settlements and colonies.

All quotes are from the chapter ‘The Pains of Imprisonment’, in Gresham M. Sykes, The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison (Princeton University Press, 1958). On the ‘total institution’, see Erving Goffman, Asylums: essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates (Anchor Books, 1961).

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Recent Comments