In the 1840s, campaigners for the abolition of convict transportation engaged in a campaign of scare-mongering about the prevalence of sexual acts between male convicts (dubbed “unnatural acts”). This strand of anti-transportation rheotirc was particularly effective because it suggested that a system that was supposed to engender moral reform actually produced moral degradation.[1] Panic about rampant homosexual activity was all the more pronounced in male-only penal stations, due to their demography and supposedly entrenched criminality of convicts, as well as the invisibility of the institutions from the general public. Norfolk Island was the locus of these fears, but similar concerns were voiced about Darlington Probation Station (Maria Island), Hyde Park Barracks and my case-study Cockatoo Island.[2]

Instead of focusing on the mythmaking of Abolitionist discourses (as Tim Causer discusses here) , or the general prevalence of homosexual acts in convict establishments (as Ben Bethell dicusses here), this blog looks at some ‘archival fragments’ that survive about an intimate encounter between two inmates – both named Frederick – on Cockatoo Island Penal Establishment.[3] Two short depositions for a court-case that was not prosecuted survive – and can tell us surprising amounts about the search for intimacy (or even love?) within the convict establishment. Frederick B. was transported to New South Wales in 1837 for stealing lead.[4] He ended up on Cockatoo Island after receiving a 12-month sentence at Hyde Park Barracks in 1845. [5] Frederick W. was transported for 10 years for stealing shirts in 1839.[6] In 1843 he was sentenced at Hyde Park Barracks, to complete ‘the residue of his sentence’ at Cockatoo Island.[7]

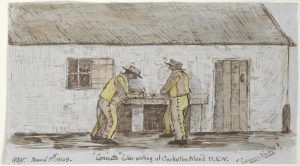

Philip Doyne Vigors, “Convicts” letter writing at Cockatoo Island, 1 March 1849, State Library of New South Wales

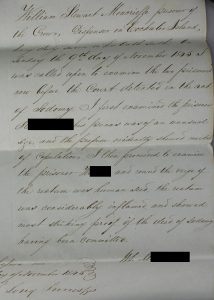

The two Fredericks were caught in the act of sexual intercourse within the prison by an unnamed witness (probably the convict guard James C.) on the 13th November 1845. They were examined by the convict medical dispenser (William M.): an intimate form of surveillance to re-assert control as soon as possible after the moment of transgression.[1] Homosexual acts can be viewed as a resistant act in the carceral context: it directly contravenes both prison rules, and wider anti-sodomy laws.[2] William M.’s examination was not only invasive, but immediate: and described in detail the physical signs of anal intercourse on both prisoners (including swellings, abrasion and secretion). In the first half of the nineteenth century, medical expert testimony became an established part of legal proceedings, a development reflected in the court records in this case.[3] Yet, medical ‘markers’ of sodomy were barely theorised until the 1850s (with writings of Ambroise Tardieu, Johann Casper and William Acton).[4] Most cases of homosexual activity were prosecuted by a witness to the act: though in this case it states only that the prisoners were ‘detected in the act of sodomy’, without naming or providing testimony by the witness. Historian Harry Cocks notes that the ‘unspeakable’ nature of the crime led to the destruction of much of the court-record of these cases in England.[5] It is possible that part of the record was expunged; though this sits uneasily with the graphic detail of the medical dispenser’s testimony. It may have been this lack of eyewitness that led the case to be dropped by the attorney general.

Deposition of the Medical Dispenser (William S.M.), 9/6332, 13 Nov. 1845, State Records New South Wales

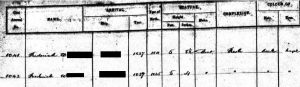

Despite having had their bodies rendered ‘objects’ for medical examination, one of the Fredericks’ voice emerges towards the end of the court depositions. While escorting the prisoners to the solitary sells (to punish and isolate them from each other) convict overseer James C. testified that Frederick B. said to Frederick W. ‘ “This is a purty [pretty] job you have led me into I shall get lagged now” ’. Frederick B’s statement implies that Frederick W. initiated the sexual encounter. Without this testimony, the physical evidence implied an power dynamic in the favour of the former: B. towered over W. (standing at 174 cm to W. below-average height of 162 cm), was 14 years his senior (W. was just 18 years old) and was in the dominant position during intercourse.[1] Consensual male-on-male sex acts could function as a means of seeking intimacy within the depersonalizing and violent regimes of the prison – and it seems that this was the case here.[2] It is worth remembering that convicts did seek solace through physical intimacy, in contrast to the ‘moral degradation’ narratives that prevailed in the abolitionist imaginary.

Register of Darlinghurst Gaol, shows joint arrival of Frederick “B” and “W”, 14 Nov. 1845, State Records Office of NSW, roll 857

The two Fredericks were sent to Darlinghurst Gaol to await trial the very next day (14th November).[1] The depositions of the convict guard and medical dispenser were sent to the Attorney General by the visiting magistrate for further advice. I have not been able to find archival evidence showing that Frederick B. and Frederick W. were brought to trial (I am 17,000 kilometres away from the archives at present). But Cockatoo Island’s registers show that the Fredericks were received back on Cockatoo Island together on 12 Jan 1847 (2 years and 2 months after leaving). They served another eight months on the island, and were both discharged back to Hyde Park Barracks, only a few days apart, in September 1847. Though I have not/cannot find the evidence in the archives I can’t help but imagine that their parallel paths to different carceral sites might meant that they continued to find intimacy or love with the other ‘Frederick’.

[1] SRNSW, microfilm roll. 857, Gaol Description and Entrance Books, 1818-1930, available via Ancestry.com. On analysing height data see: H. Maxwell, M. Cracknell and K. Inwood, ‘Height, Crime and Colonial History’, Law, Crime and History, 1 (2015) , pp. 32-33.

[2] M. Bosworth and E. Carrabine, ‘Reassessing Resistance: Race, gender and sexuality in prison’, Punishment & Society, 3:4 (2001), p. 512

[1] SRNSW, 9/6332, Clerk of the Peace Depositions, Cockatoo Island “12” & “13, Regina vs. Frederick B. and Frederick W., 13 Nov. 1845

[2] A.D. Harvey,. ‘Prosecutions for Sodomy in England at the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century’, The Historical Journal, 21:4 (1978), p. 941; B. Kercher, ‘Perish or Prosper: The Law and Convict Transportation in the British Empire, 1700-1850’, Law and History Review, 21:3 (2003), p. 539.

[3] C. Crawford ‘A Scientific Profession: Medical reform and forensic medicine in British periodicals of early nineteenth century’, in R. French and A. Wear (eds), British Medicine in the Age of Reform (Abingdon: Routledge, 1991), p. 205

[4] I. Crozier and G. Rees, ‘Making a Space for Medical Expertise: Medical Knowledge of Sexual Assault and the Construction of Boundaries between Forensic Medicine and the Law in Late Nineteenth-Century England’, Law, Culture and the Humanities, 8: 2 (2012), p. 297

[5] H.G. Cocks, Nameless Offences: Homosexual Desire in Nineteenth-Century England (London & New York: I.B. Tauris, 2003)

[1]; K. Reid, Gender, crime and empire: convicts, settlers and the state in early colonial Australia (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), p. 21; K. Mckenzie, Scandal in the Colonies: Sydney and Cape Town, 1820-1850 pp. 148-149

[2] T. Causer, ‘Anti-Transportation, “unnatural crime” and the “horrors” of Norfolk Island’, Journal of Australian Colonial History, vol. 14 (2012), pp.230-40; Gilchrist, C. ‘Space, Sexuality and Convict Resistance in Van Diemen’s Land: The Limits of Repression?’, Eras, no. 6 (2004), n.p.

[3] Due to the sensitive nature of this material, the full names and biographical details of the parties involved have been censored, but are accessible in the original archival document: State Records New South Wales (SRNSW), 9/6332, Clerk of the Peace Depositions, Cockatoo Island “12” & “13”, Regina vs. Frederick B. and Frederick W., 13 Nov. 1845

[4] Old Bailey Online. Further details not released for privacy reasons.

[5] SRNSW, 2/8285, Cockatoo Island Penal Establishment, Entrance Book, pp. 7-2; 11-12.

[6] Old Bailey Online. Further details not released for privacy reasons.

[7] SRNSW, 2/8285, Cockatoo Island Penal Establishment, Entrance Book, pp. 163-64, 167-68.

Subscribe to Katy Roscoe's posts

Subscribe to Katy Roscoe's posts

Recent Comments