By Anna McKay, AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Partnership Student, National Maritime Museum & University of Leicester.

As a relatively new addition to the University of Leicester’s School of History and the Carceral Archipelago project, over the last few months I feel as if I’ve undergone a thorough “academic baptism”. Since beginning my PhD studies in September, I’ve attended some really excellent and thought-provoking lectures, conferences and workshops both at the University of Leicester and further afield. My project, The History of British Prison Hulks, 1776-1864, forms a collaboration between the University of Leicester and the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. My primary research goal will be to fill the (many) gaps in academic literature on the subject and at this early stage I’m now ready to acknowledge that three years of PhD study will not constitute enough time to cover the broad history of the hulks.

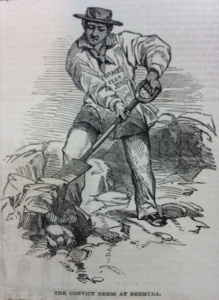

Prison hulks were decommissioned and dismantled warships, stripped of their masts, rigging and sails, and converted into makeshift prisons which could hold well over 500 prisoners at any one time. Originally conceived as a short-term solution to the prison housing crisis in the aftermath of the American Revolution, these floating prisons were moored up in estuaries neighbouring the Royal Naval Dockyards of Portsmouth, Plymouth and the Thames, even as far afield as Britain’s strategic outposts in Bermuda and Gibraltar. The hulks formed part of the British carceral landscape for eighty years, with prisoners providing a source of labour for dockyard repairs. The hulks themselves have gone down in history (thanks to Great Expectations) as “hell on water”; I’ll be investigating the truth behind this image, drawing on a varied range of source materials, from private letters and journals to administrative records and newspaper reports.

However, with a date range so vast, and a history so varied thanks to changes in hulk administration and purpose, I don’t feel any embarrassment in admitting that I’m feeling a little swamped with information! I want to document as much as I possibly can, and each new piece of secondary reading is bringing up new questions that I’m looking forward to investigating over the next few years. One such avenue for future exploration came thanks to the “Conceptualising Islands in History: A Postgraduate and Early Career Research Workshop”, which took place at the University of Leicester on the 23rd February, organised by Reshaad Durgahee at the University of Nottingham and the Carceral Archipelago’s own Katy Roscoe.

We started the day with words from the workshop’s keynote speakers, University of Leicester’s Clare Anderson, Ilan Kelman from the UCL Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction, University College London, and Sarah Longair from the British Museum, before launching into a mammoth set of twenty individual research introductions from attendees, ending with a roundtable discussion. Over the course of the day, we considered the geographies of islands, their objects, their government, connectedness and their isolation. Preparation for the event gave me the opportunity to engage with a discipline and authors which were new to me (selected works of Godfrey Baldacchino, Pete Hay, Epeli Hau’ofa and Stephen A. Royle). However, the marked individuality of each researcher’s projects on the day brought the work alive and most importantly, showed me that through collaboration and exchange of ideas, it is possible for researchers to create an interlocking and complimentary map of island biographies.

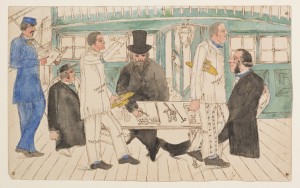

Taking part in the workshop provided me with an excellent opportunity to begin exploring a particularly overlooked chapter in the history of hulk administration; that of Bermuda and Gibraltar. With prisons overcrowding and no stable solution on the horizon, in 1823, an Act of George IV authorised transportation to any British colony. Prisoners began to arrive in Bermuda from 1824, with Gibraltar following some time later, in 1842 [1]. There is unfortunately very little literature on the British hulks moored in Gibraltar; further archival trips are set to uncover their precise role, but we do know that convicts were shipped from Britain to both outposts in their thousands and were mainly men in their early twenties, with varying degrees of literacy. In the years of the Great Famine, a considerable portion of prisoners based in Bermuda were Irish, leading to the instalment of Catholic priests who required their own boats in order to travel between the hulks moored off Bermuda’s dockyard basin [2]. As documented in Clare Anderson’s previous blog post, The Convict Hulks of Bermuda, prisoners levelled the land, constructed roads and carried out major restructuring of the dockyards themselves.

Illustrated London News, 17 June 1848.

Illustrated London News, 29 July 1848.

Island-specific issues with the prison hulks that occur in my reading are primarily linked to the climate; there were constant outbreaks of disease, complaints of poor ventilation, and the dilapidated ships themselves began to rot in the water. I find myself beginning to ask questions related to identity and connectedness; did the prisoners still feel “British” in this shocking new climate, so far removed from home? Was the threat of being sent to Bermuda or Gibraltar enough to act as a deterrent? Most importantly, how connected to the Metropole did the government view these “outpost” islands? Epeli Hau’ofa’s “Our Sea of Islands” (1994) makes the point that nineteenth-century imperialism erected boundaries; islands were often reduced simply to territories which became places of confinement for all residents as colonial lines were drawn across the ocean [3]. But in terms of my research, these lines supported colonial communication and the hulk establishment’s network; a trip to the National Archives at Kew was enough to prove that at least in terms of Home Office and Admiralty administration, the hulks in Bermuda weren’t classified as different to those moored up in the Thames. This information prompts me to delve deeper and view island hulks as forming part of a global British administrative superstructure that was not constrained by the ocean.

State Library of New South Wales, PXA280, Sketches of convicts: Comptrol[l]er and convicts, Bermuda, 1860.

The “Conceptualising Islands in History” workshop provided a great opportunity to meet island scholars and exchange ideas. It was a pleasure to hear about everyone’s research and personally, I found it very encouraging that though our research topics were vastly different; Island Studies does not seem to discriminate between a theoretical, practice-based, or case-study approach. The flexibility of the field is its strength; this diversity opened my eyes to a perspective entirely new to me but which struck a chord with my own research and I hope that there will be the scope to consider the “Islandness” of hulks over the course of my PhD. Perhaps I can even come to view the hulks themselves as virtual “floating islands”; they are, after all, carceral spaces surrounded by water. Whatever the outcome of my research, I hope that there will be the opportunity to attend similar events in the future; this is a network of scholars which still has such a lot to discuss.

[1] Constantine, S. (1958) Community and Identity: The making of modern Gibraltar since 1704. Manchester University Press.

[2] Hollis Hallett, C.F.E., (1999) Forty years of convict labour: Bermuda 1823-1863. Bermuda: Juniperhill Press.

[3] Hau’ofa, E. (1994) ‘Our Sea of Islands’, The Contemporary Pacific, 6(1), pp. 148-161.

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Recent Comments