In the early 1990s I had the privilege of studying with David Garland, then teaching and researching in Edinburgh University’s Law School. He had recently published a wonderful book – Punishment and Modern Society: a study in social theory – which remains as relevant and important today as it was then. Week by week, Professor Garland took his undergraduate class through the sociology of punishment. Together we explored themes of social solidarity, authority, political economy, power and culture; engaging with the work of Michel Foucault, Georg Rusche and Otto Kirchheimer, Émile Durkheim and Norbert Elias. We discussed and critiqued their thinking, bringing their insights to bear on each other, and arguing for the importance of an historically grounded appreciation of the state of punishment in the last decade of the twentieth century.

At the time I was in the last year of my History-Sociology degree, and in the other half of my studies I was most interested in the history of the British Empire. My honours year studies centred on work with the inspirational Ian Duffield, and the forced migration of convicts from the British metropole to the penal colonies of Australia. As I moved from class and class (and across the three disciplines of law, sociology and history) I was perplexed. How were Empire and penal colonies so absent from the penological cannon? How would the historical sociology of punishment look if we gazed outwards towards – or even first opened our eyes beyond – Europe and North America? How did imperial powers use punishment to manage populations? Where would the power relations born out of the rapaciousness of imperialism fit theoretically? In what ways would different modes of production and culture matter? Where do race, gender, enslavement and Indigeneity fit? What about the relationship between metropole and colony – or what Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler later theorised as the ‘Tensions of Empire’? And, how about non-European imperial polities like Japan? It is these very simple to ask, but very difficult to answer questions that have developed and engaged me in the years since. Where, in sum, does the history of convict transportation and penal colonies fit in sociological theories of punishment and society?

It is well known that Foucault never engaged with France’s history of penal transportation – or at least its history of attempted penal colonization – through the use of what the state called transportés-colons (transportation-colonists), or convicts. For Foucault, it was the opening of the French juvenile reformatory of Mettray, north of Tours in the Loire, in 1839, that marked the most important change in the development of what he understood to be the modern prison. This shift was, he argued, underpinned by a shift from the punishment of the body to the punishment of the soul; from the infliction of pain to carceral regulation.

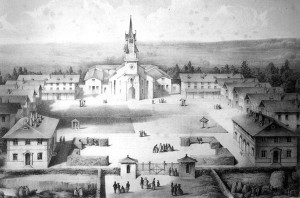

Mettray Juvenile Reformatory, France

It is a little known fact, however, that amongst Mettray’s juvenile inmates were a few children born of convict parents in the French penal colony of Guyane. And their presence in a carceral space far distant from their birthplace was by no means exceptional, for prisoners and convicts moved multi-dimensionally and in a state of near constant mobility through houses of correction, penitentiaries, hulks (penitenciers-flottants), reformatories and agricultural colonies, as well as the penal colonies of Guyane and Nouvelle-Calédonie.

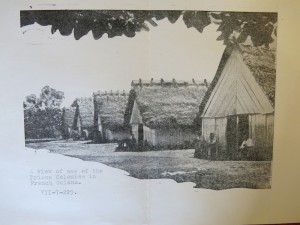

Camp de la Transportation, Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, Guyane

However, the penal colonies themselves incorporated diverse architectures of confinement, and convicts were kept in all kinds of carceral spaces. They included barracks, prisons, and convict villages; as well as solitary cells and agricultural colonies. They were not always subject to the minute observation and regimented penal rhythms that Foucault described so brilliantly in Discipline and Punish (1977). In Guyane, some convicts could undertake wage labour for local inhabitants and free settlers. They could marry each other, set up households, and have children. They were sometimes given concessions of land. The complexities of convict legal status left many destitute in the years after they had served their sentence but in practice could not leave the colony. By the 1930s about half of these ‘liberated’ men had disappeared from the purview of the French colonial state.

Source: Salvation Army Heritage Centre, London

If elements of the penal regime of Guyane challenge us sociologically, it is also important to note that transportation to penal colonies did not signal the end of physical chastisement. Convicts were under sentences of hard labour and they were employed in backbreaking work in ateliers and forests, and on roads and railroads, through which it was believed that attachment to the soil would be forged, colonization effected, and moral redemption achieved. They could be made to wear heavy fetters (irons), or be subject to solitary confinement in dark cells, reduced rations or flogging. In extreme cases of post-transportation murder, convicts were guillotined. Guyane was not exceptional in any of these respects; such regimes were typical of penal colonies from the late eighteenth century on, including for the British Empire the Australian colonies, the Straits Settlements and the Andaman Islands, and for Japan at the turn of the twentieth century, the penal colonies of Hokkaido.

If we understand the history of punishment in modern France (and Britain and Japan) as a connected history in which metropole and empire, as well as the carceral spaces that he articulated, were interlinked, what happens to Foucault’s thinking on discipline and punishment? How does it change when we incorporate penal colonies? Fundamentally, it is important that we do not claim universality for any theoretical work that is generated in the global north without due attention to the empires once claimed by that geopolitical zone – or without due attention to non-European empires and polities tout court. Moreover, penal colonies – the carceral spaces that confront us when we take a connected history approach and look beyond European metropoles – do not seem to fit into his vision of penal modernity. There was no smooth transition from the corporal to the carceral; penal colonies retained the legal right to punish convict bodies and held on to it with remarkable tenacity. Can we interpret penal colonies as part of this penal stage, components of an overall penal transition, for ultimately in the European empires at least incarceration did replace penal transportation? Portugal retained penal transportation to and between its African colonies of Mozambique and Angola until 1932. Guyane only closed in 1952. Convicts were sent to the Andaman Islands right up to the Second World War. Until then, as I noted above, penal colonies coexisted with and incorporated other archaeologies of confinement, including the penitentiary. Other forms of confinement did not replace them. A key element of convict punishment remained the exaction of physical pain through work.

I mentioned above the relative absence of Empire in the sociology of punishment, and described how this has been the theoretical starting point for much of my research. Unlike the classics of penology, scholars working in other fields such as historical geography, anthropology, subaltern studies and new imperial history are now critically engaged with bringing together – with bringing into the same frame of analysis – metropoles and colonies. It is no longer feasible to disaggregate Europe from its empires, to understand domestic and imperial economic, social and cultural formations as somehow unconnected. For example, within the history of punishment in Britain and its Empire, it is clear that innovations in prison design and convict management, and changes in practices of execution (notably the shift to private hangings), emerged in the colonies. The largest cellular prison in the world in the 1830s was not in Europe or the USA, but in Agra, India. It was the Australian states of New South Wales, Victoria and Van Diemen’s Land, as well as the colony of Mauritius, that first abolished public hangings, in the 1850s, pre-dating the 1868 abolition in Britain.

There were other clear terrains of metropolitan/ colonial distinction too, and these have a bearing on explaining punishment and experience of punishment beyond Europe. As my in-progress quantification of the peaks and troughs in Asian convict flows is showing, during the long period 1787-1939 the British in India used penal transportation for repressive purposes after rebellions and uprisings, and against politically active nationalists, to a much greater extent than did the metropolitan authorities in the first half of the nineteenth century. Quantitative data also shows that this was also the case in the Caribbean, during the period from the late eighteenth century to the prohibition of penal transportation to the Australian colonies in 1837, when transportation was used as a means of managing enslaved and formerly enslaved men and women, including after revolts. In this sense, of course, transportation can be interpreted as a means of population management, or governmentality. Foucault’s writings on power – and in particular bio-power – are truly insightful.

I next turn to Marxian ideas about punishment, and the relationship between penal transportation and political economy. It is now widely accepted that convicts were used for the outward expansion of Empire, for instance from Britain to Australia in the context of imperial rivalry with the French. Our work on the Carceral Archipelago project is also showing its value in offering a highly mobile and circulatory workforce in numerous other contexts, including early-modern Spanish America, in pushing back imperial frontiers, and in creating means of settling borderlands – as well as its use as a tool of political repression. If we think with a broad range of theories of imperialism – of gentlemanly capitalism, the drain of wealth and so on – as well as postcolonial thought that has turned our attention to important issues of race and gender; if we accept that penal transportation had an economic function too, might a penology derived from Marxian principles work for us?

The foundational Marxist text on punishment is Georg Rusche and Otto Kirchheimer’s Punishment and Social Structure (1939). They conceptualised punishment as a social phenomena shaped by political economy. Their influence on Foucault is evident, for they earlier described stages of penal transitions from the early to late Middle Ages (the latter characterised by corporal barbarity), to capitalism (where convict labour was exploited), and the post-Enlightenment rise of the prison. And, yet, as we have seen, once we take empire into account, we see that the exploitation of convict labour remained a key feature of the punishment of transportation, and this labour exploitation endured in the post-Enlightenment age. In recent published work, the carceral archipelago team has written not of the triumphant age of the prison in the nineteenth century, but of the triumphant rise of penal labour relocation. It is only by incorporating the global into the sociology of punishment that we are able to make this connection.

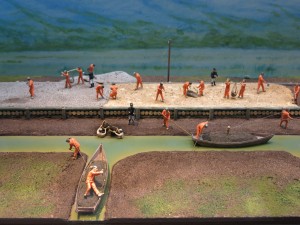

Model of convicts at work: Tsukigata Prison Museum, Hokkaido, Japan

In connecting convict transportation to labour mobility more broadly, we can see that there were massive differences across contexts. In some places, including Saint-Laurent in Guyane as well as the Australian colonies, convict transportation co-existed with extensive free migration. In others, convicts presented a form of labour competition with the people already living in what became penal sites. Thus a global approach to the history of punishment encourages us to link theories of punishment to theories of labour. The key point, here I think, is to appreciate the particularity of local circumstance; to remain attentive to diverse contexts – as well as changes over time in them – within the global story of forced convict migration that we are trying to tell. It is in this respect, perhaps, that sociology and history can most fruitfully come together, to generate a theory of punishment since the late eighteenth century that takes account of penal colonies and coerced labour mobility. By necessity, this involves global connections, to appreciate fully the relationship between Europe and its empires, and between labour flows – as well as convict transportation by other national and imperial powers.

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Recent Comments