In modern day Australia there are two key heritage ‘issues’ that are addressed in completely different ways – firstly, convict heritage; secondly, histories of aboriginal contact and conflict with European settlers. I will explore the tensions between the two narratives that emerge in the heritage of Rottnest Island, which held convicted Aboriginals between 1839 and 1931. I argue that to negotiate the guilt felt by local visitors, the Rottnest Island board has chosen to sideline and largely negate the island’s carceral history, replacing it instead with a generic narrative of Aboriginal land rights.

Rottnest Island is a very popular tourist destination

Rottnest Island is a very popular tourist destination

Convict Heritage

Convict heritage has enjoyed a resurgence in recent times. Thanks largely to the efforts of family historians, the Australian public has shed what Babette Smith called ‘the convict birthstain’. This changing attitude was marked by UNESCO granting 11 convict sites ‘world heritage’ status in 2010. UNESCO places particular emphasis on connecting these respective locations to a wider history of penal, political and colonial policy. Other convict heritage sites are equally popular, if less sensitively drawn, with increasing numbers going on prison ‘ghost tours’ or ‘tales of escape’ talks which risk overstating the grisly repression of the state and as a result exaggerate the convicts as working class heroes. Nevertheless the convict legacies of Australia have become a huge industry, drawing local, national and international tourists away from the beaches and towards Australia’s history.

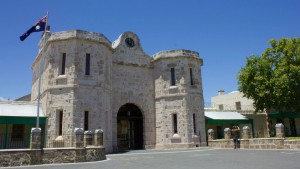

Fremantle Prison has UNESCO heritage status

Fremantle Prison has UNESCO heritage status

Aboriginal History

The negation of Aboriginals within Australian historiography was challenged by W.H. Stanner in his 1967 Boyer Lecture entitled “The Great Australian Silence”. From the 1980s the violence suffered by Aboriginal communities at the hands of settler colonists was brought to the forefront by historians like Henry Reynolds and Lyndall Ryan. In the public sphere the verdict of Mabo in 1992 saw ‘terra nullius’ overturned in favour of indigenous land rights. The 1990s witnessed a backlash against what Blainey termed ‘black armband’ history. Prime Minister John Howard refused to apologise for the ‘stolen generations’ when the Bringing them Home report was published in 1997. More recently, Keith Windschuttle’s The Fabrication of Aboriginal History (2002) claimed that ‘liberal’ historians had exaggerated the scale of violence in the colonisation modern-day Tasmania. His claims sparked the “History Wars” as Henry Reynolds bit back at Windschuttle’s ‘white blindfold’ view of history. Today, the dispossession of Aborigines is frequently recognised by the inclusion of a statement recognising Aboriginal communities as the true owners of ‘this land’ as a preface to speeches. However, specific sites of massacre are often bereft of physical features (at least to a non-Aboriginal eye) and are too rarely commemorated. The contemporary international visitor to Australia will mostly encounter Aboriginal art, in museums and tourist shops, or Aboriginal culture, through tours and dance. Though much of this art is overtly political, many tourists are searching for an ahistoric ‘authenticity’ which help them elide fraught histories of dispossession.

Material Histories

As I walked around the buildings that made up the colonial settlement of Rottnest Island – an Aboriginal prison – there were interpretation boards in front of many of the buildings that dated from its time as a prison island. The majority of these interpretation boards focused on the role of Europeans. For example the board by the store house emphasised Superintendent’s Vincent’s design aesthetic rather than those convicts who built it brick by painstaking brick. The key building – the prison ‘Quod’ had no plaque or interpretation board at all to acknowledge its former role. Instead, the walls, and with it the history, has been literally whitewashed, transforming it from Aboriginal prison to ‘luxury accommodation’.

The old prison building is now Rottnest Lodge

The old prison building is now Rottnest Lodge

Few would realise while in the ‘Governors Sports Bar’ that Governors used to holiday there thanks to the team of six Aboriginal prisoners who waited on them hand on foot. Just as the governors sipped drinks in willing blindness to the illegal chaining and bouts of disease that ravaged the prison population, tourists sip drinks in willing blindness to the history of Aboriginal injustice to which their ancestors are party.

Gov’s sports bar plays up Rottnest’s history as a leisure resort

Gov’s sports bar plays up Rottnest’s history as a leisure resort

Burial Ground

We visited the only burial ground for Aboriginal convicts, out of three, that is marked as a site of remembrance. For more than twenty years battles raged between Indigenous activists and the Rottnest Island Board about commemorating the area. The area is now marked off by a barrier warning trespassers and informing visitors that this area will be left ‘natural’. Rather than using gravestones and plaques that are familiar to most visitors, it asks tourists to take part in a commemorative ceremony that connects them to the land by picking up the soil and speaking to the Aboriginal ownership of this land. Myself and my other half did so, but I had to wonder how many were interested in connecting with commemoration when it took place in peripheral spaces so easy to bypass for the majority of visitors. This voluntary act does not divest the Rottnest Island Board from their responsibility to put Rottnest carceral history in places visitors will encounter it.

One of three burial sites for Aboriginal convicts

One of three burial sites for Aboriginal convicts

‘Welcome to Wadjemup’?

As I exited the island towards the boat that would take me home I saw the sign that had welcomed me there in a new light. The sign said ‘Welcome to Wadjemup’- as the island is known to the Noongar. As I left I was troubled by it in a way I had not been when I arrived. Its tenuous acknowledgement of Aboriginal land rights rested on a disconnection to the particular history of the island. Calling the island Wadjemup may recognise the island as a key place within the cultural geography of the Noongar. What it does not do is recognise the island as a penal institution – a place where Aboriginal people actually lived, worked, and died. All of Australia was owned by the Indigenous, but this site is the only colonial prison designed specifically for the mass incarceration of Aboriginal people. On other sites the material history of injustice towards Indigenous communities is harder to see, but here it is hard to ignore – and yet it somehow is ignored. To properly remember the island we must remember Wadjemup (as Aboriginal land) and Rottnest (as the site of colonial injustice) equally.

‘Welcoming you toWadjemup’ sign

‘Welcoming you toWadjemup’ sign

Subscribe to Katy Roscoe's posts

Subscribe to Katy Roscoe's posts

[…] posts in this blog – Bermuda and Cape Town, Eureka Henrich on Sydney and Katherine Roscoe on Rottnest Island. However, I repeatedly, and somehow irritatingly, bumped into the ubiquitous presence of one issue […]