During a recent trip to Portugal I took the chance to visit the fortress of Peniche, situated on the rocky coast in the homonymous village, approximately one hundred kilometres north of Lisbon.

The imposing fortress was built between the sixteenth and the early seventeenth centuries as part of a system of coastal defense against foreign invaders and maintained its military function until 1897. Since then, its penal function emerged: it was used as a shelter to Boer refugees transported from the Portuguese colony of Mozambique on the eve of the British seize of South Africa; it became a forced residence for the German and Austrian POWs during WWI; and was then turned into an infamous maximum security prison for political dissenters during the dictatorship of the Estado Novo (1934-1974).

An interesting exhibition focuses on this latest period. The perspective is explicitly political: a coherent story is told across multiple locations within the fortress that constitutes the site as a lieu de mémoire of the repression and resistance of the 2,487 political prisoners held during those decades. A placard just to the right side of the entrance of the castle serves the same purpose.

Most of the convicts were communist, with some socialists, anarchists and members of other anti-fascist organizations also being represented. The repressive mechanisms that led them to the fortress-prison are evocated in the first part of the exhibition, located in two relatively large rooms of what must have been the administrative wing of the prison. Besides providing basic information on the dictatorship and the antifascist movement in Portugal, sources are shown that point the role of special courts and various police and military corps, including the ubiquitous Policia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado (PIDE, the secret political police).

One document also sets the place of Fort Peniche in the broader network of punishment created by dictatorship Salazar and his successors, and alerts on the entanglements of imprisonment and overseas transportation. Out of a total of 1,417 political prisoners existing on 30 December 1937, 1,055 were held on various locations within Portugal (Peniche, Angra do Heroísmo, Porto, Lisbon and minor sites), while the rest were transported to Timor, Guinea, Mozambique and Cape Verde (the latter location referred to the so-called “Camp of the Slow Death” of Tarrafal, active between 1936 and 1954 and then again between 1961 and 1974 in order to host anti-colonial fighters).

As we proceed into the fort, selected aspects of the prison regime are highlighted. The visit slots, with glasses dividing the prisoner from their relatives, are a powerful symbol of the inside-outside separation imposed by imprisonment, reinforced by pictures of visiting children and wives in the late 1960s and late 1970s hanging on the walls in a nearby room.

The isolation cells testimony of the spatial differentiation within the fortress and its architectonic symbolism. They were placed in a separate block on the other side of a vast patio, exposed to the highest level of humidity as the building is located on the cliff face over the ocean and the seven cells doors are in the open air.

At some fifty meters distance from the isolation cells, behind an internal wall, the prison courtyard lies between the chapel and two three-stored buildings that hosted the cells.

The internal division of the punitive spaces reflects the changes introduced in 1956, when a shift occurred from imprisonment in collective cells, modelled on the previous army barracks, to a more articulated regime that featured 2-3 beds cells in the two lower wings and solitary confinement in the third floor. At present, the former are used for parallel exhibitions on local folklore and sea-related practices, while the latter are preserved and included in the prison exhibition.

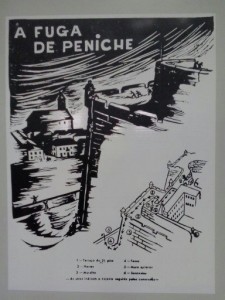

Traces of resistance are superimposed to those of repression in literally all the locations of the exhibition, reinforcing the central political narrative of continuous conflict between two clear-cut forces. While this approach considerably over-simplifies the multifaceted relationships that went on in the prison, and flattens their chronological development, it does foreground multiple forms of prisoners agency: from the hand-made wooden games that broke the monotony of the time in custody, to “kites” (illegal correspondence), clandestine journals, protests and famous escapes. Of the latter, the one occurred in 3 January 1960 is certainly the most famous, not the least because it included the future Secretary general of the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP), Álvaro Cunhal.

Attention is also paid to the broader networks of resistance that centred around the Peniche fortress: from the self-help associations founded by the prisoners’ relatives to political mobilization outside the walls of the prison, and numerous testimonies of international solidarity.

Unsurprisingly, the climax of the exhibition lies in the moment of the collective liberation of the political prisoners, that took place three days after the “Carnation Revolution” of 25 April 1974 that overthrew the dictatorship after forty years.

Distance, imprisonment, resistance,: these words repeatedly pop up in the exhibition.

The fado entitled Abandono, interpreted in 1962 by the “queen of fado”, Amália Rodriguez, immerged the listeners in a similar atmosphere:

Por teu livre pensamento / Foram-te longe encerrar / Tão longe que o meu lamento / Não te consegue alcançar… [For your free thinking / They imprisoned you far away / So far that my lament / Is unable to reach you]…

Soon forbidden by the dictatorship for its evident references to the prisoners in the infamous coastal fortress, it became popular as Fado de Peniche, and a symbol of resistance.

I invite you to listen to the Fado de Peniche while taking a short visual tour of the fortress:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0-_7BqY7e-8

Bibliographical suggestions:

Fernando Miguel Bernardes, Uma Fortaleza da Resistência, Lisbon, Ediçôes Avánte, 1991.

J.M. Soarez Tavarez, O campo de concentração do Tarrafal (1936-1954). A origem e o quotidiano, Lisbon, 2007.

Subscribe to Christian De Vito's posts

Subscribe to Christian De Vito's posts

Hi. I have just visited the prison and I was wondering what the room with pillars under the courtyard was used for? There was no one to ask, and no information in English. Hope you can help!

I’m impressed, I must say. Really rarely

do I experience a website that’s both educative and entertaining, and I’d like to tell you,

you have hit the nail on the head.

I discovered your blog site on google and examine a number of your early articles.

Always keep up the good function. I simply extra

up your RSS feed. Seeking forward to reading more from you later on!

I’m impressed, I must say. Truly rarely do I experience a website that’s

both educative and interesting, and I want to let you know, you’ve struck the nail on the head.

You have a great website here! Do you want to produce some

invite articles on my blog?

Awesome blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.