In 1871, a group of men – hereditary chiefs of the Six Nations of the Grand River – met with anthropologist Horatio Hale in the town of Brantford, Ontario. The people of the Six Nations community are Haudenosaunee – the People of the Longhouse, a confederacy of nations that predates European contact with Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island (North America).[i] Many Haudenosaunee people had fought alongside the British against the American rebellion in the 18th century, and for their loyalty to the Crown, the Americans under General George Washington sacked and burned many Haudenosaunee settlements in what is now New York State. While many Haudenosaunee endured these depredations, some communities and families relocated north and west to a tract of land – called the Haldimand Tract – set aside for them by the Crown in return for their support. A century later, Hale met with the chiefs to learn about their systems of treaty making through the creation of beaded belts. Called ‘wampum belts’, these intricate and complex belts serve as the physical representation of complex treaty agreements and international relationships. However, while Hale was mostly interested in what the belts were, the chiefs of the Six Nations were trying to tell him a different story: a story about what the belts guaranteed, and how the Crown was failing to live up to its obligations.

Six Nations chiefs meet with Horatio Hale (second from left) at Brantford, Ontario, 1871.

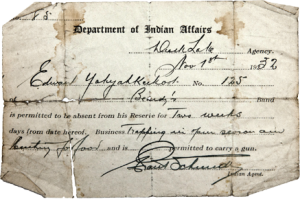

Almost from the moment that the Crown agreed to the Haldimand Tract, it began to erode this land base.[ii] Beginning in 1798 with the appearance of illegal settlements on the Tract, the space of this territory was reduced, at first in small parcels and later in large chunks, through shady business purchases, military and governmental appropriation, or simply theft by homesteaders and other settlers. Hale was learning about culture, but chiefs wanted to explain what they held was illegal loss of land – their landbase was being eroded and their own mobilities in their home territories restricted. While the Six Nations leadership could not know this for certain, some of their worst fears would be realized in 1885 with the imposition of ‘the pass system’ – a policy whereby ‘Indians’ could not leave reserve lands without express permission of an ‘Indian Agent’[iii] – and increasingly militarised and antagonistic government and police interventions into Confederacy affairs. In short order, the Six Nations of the Grand River had been turned from one part of a much larger sovereign confederacy of nations into a virtual prison, disconnected and isolated from the political, cultural, and economic life of both their own people in the United States or elsewhere in Canada, and from that of Canadian society as well.

A map showing the original Haldimand Tract (grey) and current Six Nations reserve (red) via sixnations.ca. The original grant was 950 000 acres, of which only 48 000 remain.

The story of the transformation of the Haldimand Tract is not unique in North American history. The establishment of the reserve (Canadian) and reservation (American) systems frequently involved forced relocations – such as the removals of the Tsalagi (Cherokee) and other nations to the Oklahoma territories in the early 1800s – and other acts of violent, illegal appropriation. But as I consider this meeting between Hale and the Six Nations chiefs, what strikes me is that while colonial governments stole from Indigenous nations, it has traditionally been Indigenous communities who are pathologised and treated as inherently criminal. And if Indigenous peoples viewed their lands as sovereign, then the same reversal of logic is at play when settler governments and communities began treating reserves as spaces of incarceration.

While often originally established through treaty and negotiation, settler colonial governments have rarely seen these places as other than a dumping ground for unwanted Indigenous bodies, representing the existential threat of persistent Indigenous nationhood in the lands claimed by colonial societies. Like the Haldimand Tract, the original boundaries of many reserve lands or treaty territories were frequently only respected until the land became too valuable for voracious settler economies to ignore. When this occurred, the borders of reserves were often arbitrarily shrunk even as corresponding borders between Indigenous and settler spaces were hardened by police, soldiers, and bureaucrats. During the Allotment era of American Indian Policy,[iv] for example, the US government assigned reserve land on a per-family basis, which when totalled usually fell far short of the original tribal land base recognized by the state. These ‘surplus’ lands were then severed from the reserve and sold for a profit. Unsurprisingly, these shrunken reserves became too small to support viable economies and social activities, and as years have passed, the initial economic impossibility has predictably spiralled, contributing to the massive economic deprivation that affects many Indigenous communities today. Or, for a more egregious example, consider that the entire province of British Columbia was simply annexed by the Crown in 1866, beginning the process of displacing and dispossessing dozens of Indigenous nations. Indigenous communities had to petition after the fact to even be left with a too-small-to-survive parcel of reserve land. Reserve lands, in this view, must be understood as rump territories in which Indigenous peoples have managed to maintain direct relationships to land despite centuries of genocidal displacement. But they are also, I argue, invisible prisons that betray the carceral logics at the core of settler colonialism.

An example of a ‘pass’ issued by Indian Agents (Duck Lake, 1932) – the pass system was used to prevent Indigenous peoples from leaving reserves, effectively incarcerating them. Photo via Dr. Shauneen Pete, University of Regina.

While Indigenous peoples have repeatedly articulated reserve spaces as homelands and as signifiers of the much larger territories stolen by the settler states around them, on the other side of the coin, settler people clearly think of reserves as carceral: places to constrain and store indigeneity and Indigenous peoples until they are inevitably ‘corrected’ by civilisation. That is to say, in the mind of the settler, the reserve is intended as a bare space of containment and punishment, and so Indigenous peoples on reserves are criminalised precisely because, by “settler common sense,”[v] only the criminal would choose to live in a prison. Reserve lands continue to be appropriated, polluted, or drained of economic possibility, and so more and more Indigenous people are forced to leave reserves. Yet, because settler colonialism still informs Canadian and American societies, and because an Indigenous person does not stop being Indigenous just because they are beyond the boundaries of the reserve, settler people still see these Indigenous bodies as being out of place and time, and as a threat to settler claims and belonging – in short, in need of storage and correction, if not outright elimination. And thus there is a direct, chilling line from the grievances that the Haudenosaunee chiefs raised with Hale in the 1870s, and the massive over-representation of Indigenous peoples in the Canadian and American prison systems today: carceral tactics that demobilize Indigenous communities, drain them of resources to resist encroachment, and the use of violent force to police the boundaries of ‘civilized’ space.

[i] For an accessible history of the Haudenosaunee, see digitalwampum.org.

[ii] Good accounts of the history of the Haldimand Tract can be found in: Rick Monture, We Share Our Matters: Two Centuries of Writing and Resistance at Six Nations of the Grand River, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2015; Theresa McCarthy, Divided Unity: Haudenosaunee Reclamation at Grand River, Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2016.

[iii] The Pass System remained a policy rather than a law, so never faced court challenges over its legality. While it was primarily applied in the Canadian west, it clearly indicated a nation-wide determination on the part of the state to keep ‘Indians’ on reserves and out of spaces of settlement.

[iv] Following the passage of the Dawes Act in 1887 and establishment of tribal membership rolls by the federal government – see: Frederick Hoxie, A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880-1920, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984; Jeff Corntassel and Richard Witmer, Forced Federalism: Contemporary Challenges to Indigenous Nationhood, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008; Kevin Bruyneel, The Third Space of Sovereignty: The Postcolonial Politics of U.S.-Indigenous Relations, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

[v] Mark Rifkin, Settler Common Sense: Queerness and Everyday Colonialism in the American Renaissance, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Subscribe to abarker's posts

Subscribe to abarker's posts

[…] The always amazing Adam Barker has a new blog post this week all about the relationship between Indi…. He looks specifically at how reserves and prisons acted in similar ways to contain Indigenous peoples in the service of settler colonialism. […]