As the Independence Day fireworks erupt over the Rosebowl Stadium near Los Angeles, just across the highway from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, fireworks of a very different kind should be going off at Jupiter. For 35 minutes, NASA’s Juno spacecraft will fire its main engine to apply the brakes and ease into orbit around Jupiter. This will all be happening early in the morning in the UK (around 3 am on July 5th, see detailed timings here), although I’m sure Leicester scientists will be regularly checking the internet for updates (astronomers are used to the nights, after all). This ‘Jupiter Orbital Insertion (JOI)’ will be the culmination of a five-year interplanetary cruise since the launch in August 2011, a cruise that saw the 20-metre diameter spinning spacecraft swing by the Earth in October 2013. If everything goes to plan, the spacecraft will be injected into the first of two wide, elliptical orbits around Jupiter, lasting around 100 days in total, before further manoeuvres settle Juno into a regular fortnightly polar orbit that will give Juno a unique perspective on the giant planet from mid-November onwards.

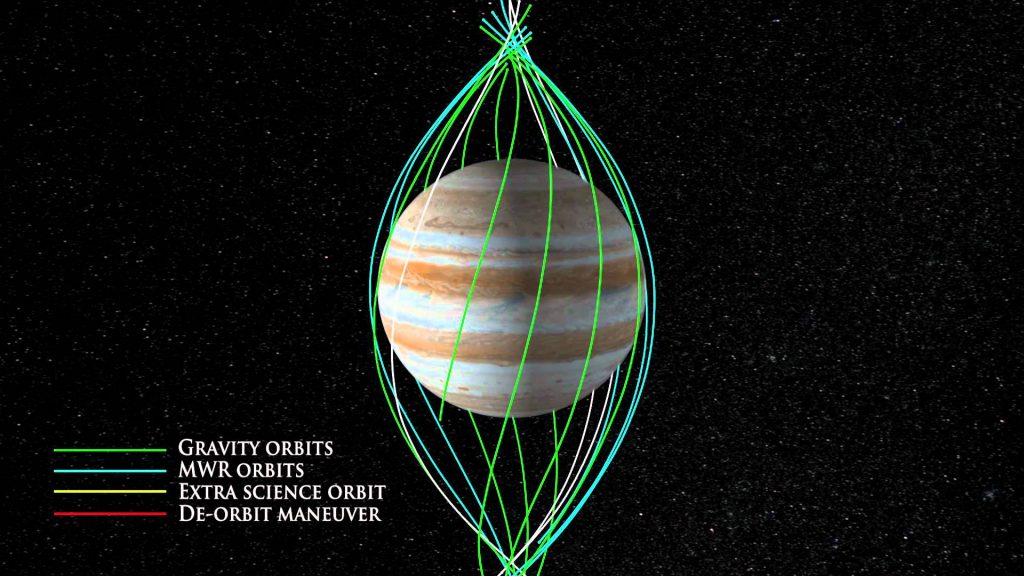

Orbit diagram for Juno showing the distribution of perijoves. An animation of this orbit can found here. Credit: NASA/JPL

This fortnightly orbit is special for a number of reasons. Firstly, with the exception of Pioneer 11 (1974), no modern spacecraft has ever been able to look down over Jupiter’s poles before. Earth-based imaging struggles to see the very highest latitudes because, unlike Saturn, Jupiter exhibits hardly any tilt. That means that Juno’s remote sensing instruments will provide our first proper glimpses of Jupiter’s polar atmosphere, and stunning new views of the auroral processes at work. Secondly, Juno’s trajectory brings it closer to the planet than any previous spacecraft mission, skimming just 5000 km (around 3100 miles) above the cloud tops at its closest approach (known as the perijoves). If Jupiter were a basket ball, its closest approach would be only a fingers-width away. That close polar orbit will give us high-resolution views of Jupiter’s atmosphere, but was essential from the perspective of mission planning, as it allows Juno to avoid most of the harsh radiation environments that sit around the planet’s equator.

Even so, Juno will be taking a pummelling from all the high-energy particles (ions and electrons) that zip around Jupiter. It will be entering one of the most extreme radiation environments that we know of, suffering the equivalent radiation dose in a single year as 100 million Xrays from your friendly dentist. That radiation will ultimately cause severe damage to Juno’s sensitive equipment, even with the electronics shielded within a vault with 1-cm thick walls of Titanium. No one can tell exactly when the spacecraft will start to suffer, but all the instruments have been designed to ensure that they can deliver their core science and possibly last a little longer. The current mission plan is to finally say goodbye to this long-suffering spacecraft in February 2018, as it burns up in Jupiter’s atmosphere like a human-made shooting star.

This polar orbit makes Juno different from previous giant planet missions like Galileo or Cassini, which have mostly stayed in the equatorial plane with some brief excursions to higher latitudes. The close proximity is also a challenge for global mapping of the planet – although polar views will be excellent, maps of the rest of the planet will be built up slowly over many months, as Juno’s successive perijoves cover different regions of the planet. That also makes it hard to track atmospheric features that evolve with time. Here’s where the ground-based support campaign steps in, providing regular global maps to provide spatial context for Juno’s observations, and also temporal context for evolving features. There’ll be more on that in later blog posts, but one tricky aspect of Juno’s arrival is the timing. Jupiter is now disappearing from our night skies as an evening object, getting closer and closer to the Sun. Conjunction is in mid-September (when we cannot view the planet at all), so imaging from Earth will be rather difficult over the next few months. Even when Jupiter returns as a dawn object in November, it’ll still be hard to get good views of what’s going on.

At the time of writing, we’re still 18 days out from arrival and waiting with baited breath. Emily Lakdawalla’s excellent post about Juno’s imaging observations (http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2016/06090600-what-to-expect-from-junocam.html) describes some of the ongoing science before arrival – at the moment, Juno is acquiring images 2-4 times per hour as Jupiter gets larger and larger out the window. We should be able to see Jupiter and the dance of its moons over 17 days, finishing on June 29th in preparation for the JOI. Juno has also been sampling the solar wind and magnetic field information as it approaches Jupiter. All fingers, toes and solar panels are crossed for Juno ahead of its arrival!

In the next blog post, we’ll look at the science case for a mission to Jupiter in more detail.

More Details:

An animation of Juno’s orbit from NASA/JPL:

Subscribe to Physics & Astronomy's posts

Subscribe to Physics & Astronomy's posts

Recent Comments