The prison of the wolvenplein (Wolves Square), located in the city centre of Utrecht (The Netherlands), closed down in June 2014 as part of the budget cuts that have also affected the prison administration. By the time of the closure, 124 persons (men and women) were imprisoned there.

The prison was built in 1856 as the second penitentiary in the country, after that of Amsterdam (1850). Expanded in 1877, its architecture witnessed the long-standing fortune enjoyed in the Netherlands by the cellular (“Pennsylvania”) regime of detention, based on the strict isolation of prisoners both at night and during the day. During that period, one of the founders of the socialist movement, Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis, was incarcerated there for seven months for lese majesty. Other inmates included less known individuals sentenced for “vagrancy”, later transferred to the “reforming house colony” of Veenhuizen, in the eastern region Drenthe (http://www.gevangenismuseum.nl/). The cellular regime lasted until 1914, and the establishment of the nationally relevant Criminologisch Instituut (Institute of Criminology) within the institution in 1934 – during a seven-year period of closure of the penitentiary – symbolises the subsequent impact of positivistic-minded criminology.

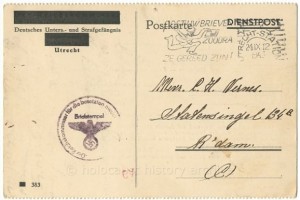

In the period of the Nazi occupation of The Netherlands (1940-1945) the penitentiary was the theatre of harsh repression and prisoner resistance.

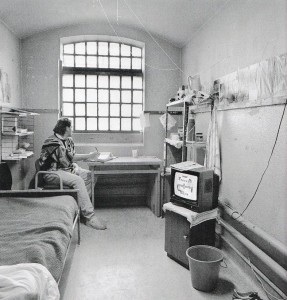

The intense history of the prison of the wolvenplein after WWII features multiple changes of the internal regime and a major refurbishment in 2000, which included the introduction of electronic surveillance and the substitution of the prison bars with security windows in each cell.

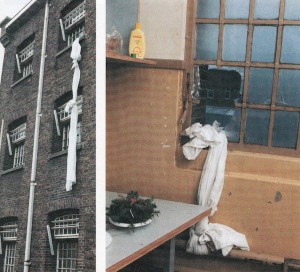

At the same time that technological changes reshaped the prison security apparatus, episodes of resistance took place, both inside and outside the prison wall.

Since the closure of the prison, and while waiting to be sold to private buyers, the building has been run by a local group, Stadsdorp Wolvenburg (http://www.wolvenburgutrecht.nl/). This has organised numerous events, including regular guided tours and exhibitions. The building presently hosts the international event Hacking Habitat – Art of Control (https://www.hackinghabitat.com/nl/), dedicated to the “rise of a remote control society colonizing and infiltrating increasing realms of daily life for the sake of safety and risk-management” (from the Concept – https://www.hackinghabitat.com/en/concept-2/). The exhibition includes the works of around eighty artists from different countries, and literally spans the globe. Imprisoned within the cells on the ground floor of the main block, the installations transmit memories of marginalisation, social control and political repression, from Francoist Spain to South Africa at the end of the apartheid and Sarajevo during the Jugoslav war, to urban areas in transition like those of Sulukule (Istanbul) and in the Chinese region of Shenzen.

Other art works convey powerful and provocative messages: one cell hosts the portraits of leaders of the financial world, whom the artist considers “responsible for the economic crisis”; in another cell, an Austrian project for a bridge between Tunisia and Sicily is presented as a way to avoid the deaths of refugees in the Mediterranean sea.

The overlapping geographies of poverty, race and imprisonment, and the exposure of what has been called the “hyper incarceration” in the USA, are the key topics of the installation by Laura Kurgan and Eric Cadora; this hangs on the opposite wall of the portrait of a “Rebel soldier committing suicide. Congo 2012”.

Virtually all art works are thought provoking, and the exhibition as a whole provides a powerful and articulated visualisation of past and present experiences of control and repression world-wide. However, as I walked from one installation to the other, I asked myself why the prison building itself, and its multiple stories, has been silenced. Indeed, there is not a single reference to the memory and history of that prison of the wolvenplein within the exhibition. Why have those walls, cells and metal doors been used as such a neutral, white screen to project “distant” stories of suffering and repression? And why did none of those stories relate to the country where that prison lies, i.e. The Netherlands?

Are the Dutch prisons and the Dutch society so “civilised” and “humane” that they can host an exhibition on social control and political repression world-wide, and call themselves out of the picture?

References:

- Herman Franke, Twee eeuwen gevangen, Het Spectrum, 1990.

- Bettina van Santen, De gevangenis aan het wolvenplein, Stichting De Plantage, 2001.

- Miranda Boone and Martin Moerings eds., Dutch Prisons, Bju Legal Publisher, 2007.

- Hans Smits, Strafrechthervormers en hemelbestormers. Opkomst en teloorgang van de Coornhert-Liga, Aksant, 2008.

- TV programme on the prison of the wolvenplein: http://www.rtvutrecht.nl/nieuws/1012198

- http://www.wolvenburgutrecht.nl/content/gevangenis-wolvenplein-historie

![Zentrum fur politische Schonheit, Die Brucke [The Bridge], 2015](https://staffblogs.le.ac.uk/carchipelago/files/2016/03/20160319_142029-300x169.jpg)

Subscribe to Christian De Vito's posts

Subscribe to Christian De Vito's posts

Recent Comments