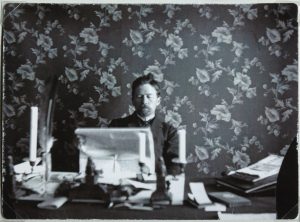

Chekhov’s contribution to the cultural landscape of the Sakhalin penal colony (1868-1905), the establishment of several school libraries containing more than 2,200 volumes for the island’s children and their convict parents, has received little attention compared with the acclaim accorded his prodigious 1890 demographic census of prisoners. “I visited every settlement and went into every hut,” he wrote.”I don’t know what will come of it, but I did a considerable amount. Enough for three dissertations. I got up at five each morning, and retired late at night, and all day I was driven by the thought that I was not doing enough . . .”

While interviewing the adult convict population for his census, Chekhov was also observing the quality of their children’s lives. His notes reflect a particular emphasis on their intellectual needs, needs that he considered were being ill met. Overwhelmed by the task of administering a fledgling, underfunded exile colony, government officials had sidelined improving the island’s educational system. Since his visit occurred during the summertime, Chekhov was not able to observe schools in session. He did notice the quality of the material educational environment, however, studied the reports of the school inspector, and interviewed the prisoners who had been tasked with teaching the children. Primary among his observations was the fact that none of the schools contained libraries.

To be fair, the fact that a system of schooling functioned at all on Sakhalin might be considered a minor miracle, regardless of its quality, considering the difficulties inherent to colonizing a region as remote from the metropole as was Sakhalin. The first colonists–convicts, soldiers, and voluntary settlers–who arrived in the 1860s had to clear land, fell timber, build homes, breed livestock, cultivate crops, mine coal, lay roads, and hunt for food despite a significant lack of equipment and manpower. Regional metric books reveal that many of the earliest families in the area had numerous young children, most of whom were too young to perform heavy labour. The families were also frequently headed by a single parent; they were, in the words of Sakhalin historian M.I Ishchenko, “indigent”.[1] Administrative officials, who were also newcomers to the island, in similar fashion had to build from the ground up both the penal colony and also the economic structures necessary for its survival.

Sakhalin’s first schools

The first school on Sakhalin was established in 1870 for the children of the soldiers in the five Russian military posts: Douai, Ilyinsk, Naybuti, Manuyski, and Korsakov. However, this school had to close its doors within a few year, the casualty of “numerous failures”. Later, in 1875, the officers of the 4th Siberian battalion at Korsakov voted to establish a school “in honor of His Majesty Prince Alexei Alexandrovich”[2] for the benefit of the children of soldiers and peasants. The first teachers were the local priest, Father Simeon, and Lieutenant Michael Kostevich, and the main subjects taught were the alphabet and the Word of God.[3] This might explain why, when Chekhov checked the schoolrooms for books in 1890, he found mostly evangelical pamphlets and a few volumes of grammar.

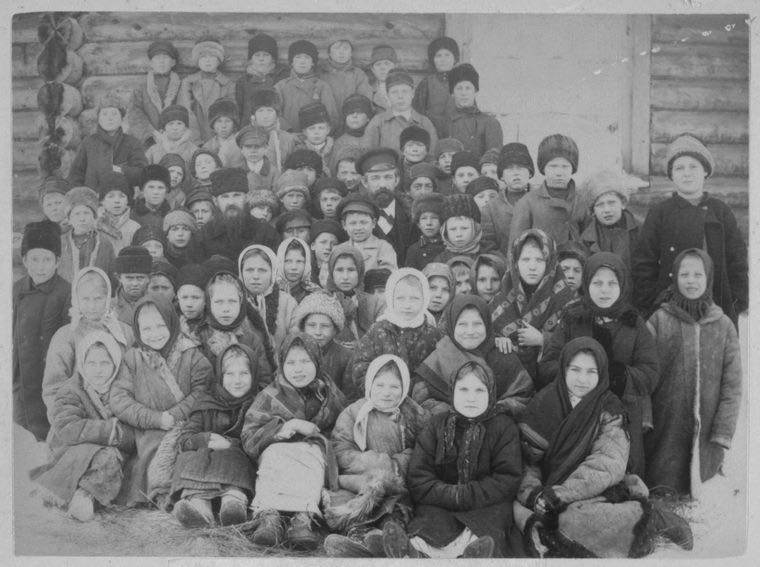

During the 1899-1890 school year, 222 children (144 boys and 78 girls) out of a total population of 700, attended the schools at an average rate of 44 students per day. Reports written by the school inspector indicate that the schools were considered to be “poor, furnished in a beggarly fashion, that their existence is only due to chance and not obligatory [ . . . ] nobody knows whether they are going to continue to exist or not.” [4]

With a few notable exceptions, most of the teachers were themselves prisoners who the penal the administration had assigned to instruct the students despite their lack of pedagogical experience and sometimes questionable “moral standing” (Chekhov summed them up as “ill-equipped for the work”).[5] N.N. Maltsev, who was the teacher in the city of Birch, taught 23 of a possible 67 children in the local school. He was also an alcoholic who, on religious holidays, would “practically ruin himself with drink”. Fedorov, school teacher in Vladimirka, was known for his inability to solve a mathematical equation.[6] Although more educated individuals could have been hired from among the population of free settlers, the penal administration would have had to pay them 25 rubles per month as opposed to the 10 rubles per month exile teachers earned.[7] In 1890, the literacy rate for both the general population and school-aged children stood at nine percent.

Overall, the development of the schools on Sakhalin mirrored the poverty of the island in general. Some of the most precise information in this regard can be read in the letters of D. A. Bulgarevich to Chekhov. “I can say with certainty that one quarter of our children do not have the basics: food, clothing, shoes, light by which to study, warmth [ . . . ] Even those children who are already enrolled in school often skip, citing the fact that they do not have coats to wear nor the necessary supplies, or that [their families needed them] to go into the forest to search for food.” Other reports describe the conditions within the schools themselves: most schoolrooms were unfurnished save for a few benches and a portrait of the tsar. Others were unheated. Almost always, Chekhov’s description of a school site concludes with the words, “a library does not exist, with the exception of a few religious books”. [8]

Assembling the library

After returning to European Russia from Sakhalin, Chekhov undertook to assemble and send to Sakhalin a high quality library. He asked his close friends for book donations, many of whom were highly educated or were also writers. Some of the first contributors to Chekhov’s “convict library” included Miziovnii, the famous Moscow lawyer, the writer A.I. Urusova, the artist I.I. Levitan, and publisher F.F. Pavelenkov. He also appealed to the Literacy Committee for assistance. When requesting donated texts, Chekhov considered not only the island’s children, but also their parents and of the luxury of thought that such volumes might afford them. As it turned out, the collection of books consisted not only of textbooks, readers, adventure stories for children, and fables, but also was rich in the work of the world’s great writers: Shakespeare, Lomonosov, Mark Twain, Tolstoi, Korolenko, Dickens, Byron, Pushkin, and many others. To these, Chekhov added numerous volumes of his own short stories. Then, he petitioned the director of the Volunteer Fleet, requesting free passage for the collection from Odessa to Sakhalin. His request was granted. March 13 Chekhov wrote to a friend, “more than 2,200 volumes were sent to Sakhalin.”[9]

Some residents of Sakhalin wrote notes of gratitude to Chekhov after the books’ arrival. One penned, “A sincere thank you for those books that were sent by you, for the good of the school here in Timovsk, and to the benefit of all those in our community.”[10]

Although such moments cannot be traced, one wonders: whether, during the years that followed, there were prisoners and students who, having taken a volume of Chekhov’s own short stories from the school shelves, and perhaps having begun to read his words . . . paused to think again about the days that the writer spent among them, and on the entirely unique nature of his visit to their penal island.

Notes:

- M.I. Ishchenko. Russkie starozhili Sakkalina: Vtoraia polovina XIX-XX vv. Iuzhno-Sakhalinsk: Sakhalinskoe Izdatel’stvo, 2007. str. 15-21.

- the brother of Alexander II.

- RSHA DV F. 1133, Op. 1, D. 142, L. 5

- M.V. Teplinskii. Sakhalinskie puteshestviia. Iuzhno-Sakhalinsk, 1962. str. 23

- Anton Chekhov. Sakhalin Island. p. 271.

- Istoriia shkoli: oli v sele Berezianki.

- Many of the clerks in the prison administration earned more than forty rubles per month, which speaks to the low regard in which school teachers were held.

- Teplinskii, p. 23

- Ibid, p. 26.

- Ibid. p. 27.

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

Recent Comments