By Kellie Moss

The sentence of transportation signified the physical removal, or banishment of convicts, from the wider social body to colonies overseas. In the case of transportation to Australia (1788-1868), convicts were not allowed to return to Britain, even after the expiration of their sentences. This permanent severance of their connections to friends, family and home has been called ‘a social death’. [1] The letters and life of Edward Langridge reveal the psychological and personal side of this punishment for convicts transported to Western Australia.

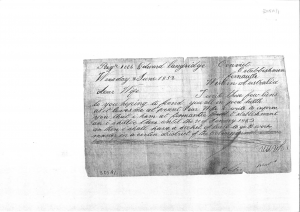

Figure 1: State Library of Western Australia MN 815, ACC 305A, an example of one of the letters that Edward Langridge wrote to his wife and daughter in Kent.

Born in Sussex in 1825, convict 1006, Edward Langridge was sentenced to 10 years at the Maidstone Assizes, Kent, on the 18th March 1850 for burglary with assault, and left Portland, England on November 2, 1851 aboard the Marion. [2] The voyage took 89 days and the Marion arrived in Fremantle on January 30, 1852 with 30 passengers and 279 convicts. [3]

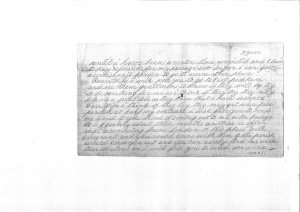

Figure 2: State Library of Western Australia MN 815, ACC 305A, Letters of Edward Langridge.

Like many convicts, Edward’s initial impulse after landing in Western Australia was to write to his wife, Susan Langridge and their daughter. Unfortunately for Edward prisoners tried at Assizes or under Summary Conviction were only permitted to write and receive letters once every three months. Furthermore, prison officers were authorised to destroy any letters which contained ‘public news, bad advice, and improper language’. Despite these limitations, Edward sent his first letter to his family in 1852 expressing his hope that they would soon be able to join him. Although families of ticket-of-leave prisoners were encouraged to apply to the government for half the cost of their passage to the colony, as Rica Erickson notes, only seven and a half percent of married couples were reunited. [4] Whilst some wives feared the long journey, or were financially unable to make the move, others were unwilling to suffer the social prejudice that convictism entailed. Although we can only speculate as to the reasons why Susan chose to ignore her husband’s requests, Edward’s letters provide insight into the struggles of convicts sentenced to transportation.

I have wrote three letters an have never had an answer… i thought that you would be the last person to turn your back on me… i wish you bouth (both) was with me an then i should be happy but now I have no won (one)…

Sadly, as Susan never replied to any of her husband’s letters, Edward’s final message to his family is a poignant reminder of the ongoing pain of familial separation that convicts endured.

Dear wife i hope that you will be sure an take care of poor little old Fanney i should like to see it so dear wife that you will answer this letter ore you may not expect to hear from me anymore if you do not so i must conclude with my love to you and all your affectionate and inesent (innocent) convicted husband.

Whilst Edward went on to marry Ann Ralph, an Irish immigrant from Tipperary, the scarcity of women in Western Australia prevented the marriages of many more expirees. [5] To appease the colonists for accepting convicts, the British government had agreed to assist by sending an equal number of free migrants to the colony. However, after 1855 the labour markets inability to absorb migrants led to a lag in emigration and a slowly increasing gender imbalance. This meant that despite their youth only twelve and a half per cent of ex-convicts went on to marry. [6] In addition to the lack of marriageable females the colonists also worked to limit the convict’s prospects by intentionally emphasising the social differences between those who were bond and free. As a result, only immigrant girls and those from the lower classes were willing to marry ex-convicts. Therefore, although some, like Edward managed to find solace and acceptance through marriage, life for many expirees remained a solitary existence as they continued to be shunned from respectable society.

[1] For more on the term ‘social death’ see: Hamish Maxwell Stewart, Lucy Frost, Chain Letters: Narrating Convict Lives (Melbourne University Press) 2001.

[2] Rica Erickson, Gillian O’Mara, Convicts in Western Australia, Dictionary of Western Australians Volume IX 1850-1887 (University of Western Australia Press) 1994, pg. 328.

[3] Charles Bateson, The Convict Ships, 1787-1868 (Brown, Son & Ferguson Ltd, Glasgow) 1969, pg. 374.

[4] Rica Erickson, The Brand on His Coat (Hesperian Press) 1983, pg. 12. Rica Erickson, The Bride Ships (Hesperian Press) 1992, pg. 177.

[5] Rica Erickson, The Bride Ships, pg. 178.

[6] Alexandra Hasluck, Unwilling Emigrants, A Study of the Convict Period in Western Australia (Oxford University Press) pg. 102.

Kellie Moss is a PhD Candidate at the University of Leicester and Affiliated Researcher with the Carceral Archipelago Project.

Subscribe to abarker's posts

Subscribe to abarker's posts

Минуту назад исследовал содержимое интернет, и к своему удивлению обнаружил познавательный ресурс. Вот посмотрите: также читайте . Для меня этот ресурс произвел радостное впечатление. Пока!