by Lorraine M. Paterson

In 1923 in the British colony of Trinidad, a young English woman returned from visiting her family in a suburb of the capital, Port of Spain, to find that her Chinese husband of six years, Lý Liễu, had packed up his possessions and left her and their two small children. A Chinese trader originally from Hong Kong, Lý had been working at a Chinese import/export company when this woman had met and married him. Now, without warning or explanation, he had vanished, presumably to return to Hong Kong. Indeed, he never returned to Trinidad or saw her, or their children, again.

In his later reminisces, Lý Liễu did not refer to his wife or children by name, but conveyed his terrible guilt at having abandoned them. In a less predictable regret, Lý expressed sadness that his wife would forever assume he was racially Chinese and would never know his real race and identity.[1] For despite his appearance, his fluency in Cantonese, his position at a Chinese company, and his years spent in Hong Kong, he was not the overseas Chinese businessman he pretended to be. In fact, he was an escaped Vietnamese political prisoner from the notoriously harsh penal colony of French Guiana, about seventeen days away from Port of Spain by boat.

Such a story goes against the stereotype of the penal colony of French Guiana, usually positioned as a hellish prison from which escape was nigh on impossible. Its horrific reputation was encapsulated by its name amongst prisoners: la guillotine seche, “the dry guillotine;” it killed slowly, but just as surely, as a guillotine.[2] Films like Papillion (1973) depict the extraordinary lengths to which prisoners had to go to escape; impersonating a Chinese businessman was not one of them.

The Society for the Encouragement of Learning

The leafy campus of St Joseph’s College, an elite Catholic secondary school in Hong Kong founded in 1875 and still enrolling students today, seems an unlikely place for a meeting that ultimately led to Lý Liễu’s double life in Trinidad. He was sent there in 1905 at the age of 12, by a forward-looking father determined he should benefit from a cosmopolitan education. At the time, Vietnam was a French colony and colonial rule was greatly resented by many colonial subjects who sought East Asian milieus in which to organize anti-colonial activities. Indeed, it was at St Joseph’s College that Lý met anti-French activists and by the time he was 15 had joined a group named the “Khuyến Du Học Hội” (“The Society for the Encouragement of Learning.”)

After leaving St Joseph’s School, Lý studied at a Centre for English Studies in Hong Kong while helping students clandestinely arriving from Vietnam and he also assisted in the broader anti-colonial effort directed by Vietnamese nationalists from various Southeast and East Asian locales.

However, all of these activities came to an end on June 16, 1913, when British authorities in Hong Kong received a tipoff and Lý and his Society associates were arrested at the house of a supporter of the movement. Some reports indicated that bomb making equipment was discovered in the house, which may be factual given British willingness to arrest them. (British reticence in arresting Vietnamese in Hong Kong without material evidence of criminal involvement often infuriated the French colonial administration of Indochina.)

This is the file of Đinh Hữu Thật from the French colonial archives – the only extant penal dossier on a member of the Society to Encourage Learning.

A criminal tribunal in Hanoi subsequently sentenced four of the group on September 5, 1913. Only one deportation dossier still exists in the French colonial archives, (a member of the Society by the name of Đinh Hữu Thật) and it cites his crime as “criminal association.” Such lack of documentation makes it difficult to determine why the length of sentence varied dramatically between different people: all had exile to French Guiana but the sentences varied from perpetual hard labour to five years of hard labour (which was Lý Liễu’s sentence, perhaps on account of his youth?) These prisoners joined a stream of over 7000 prisoners – both common-law and political – from Indochina to various points within the French empire during the period of French colonization.

Dense Jungle Toil

When they arrived in French Guiana, the group of four was assigned to a work unit to cut wood in an inland region and Lý Liễu was placed as a guard in charge of his fellow prisoners. Placing Vietnamese prisoners in charge of other Vietnamese prisoners was also a feature of the prison system in Indochina where “caplans” who were half prisoner and half guard occupied this role. [3] His many years of education in Hong Kong meant that even though he was the youngest member of the four, Lý spoke English, Cantonese, and French fluently.

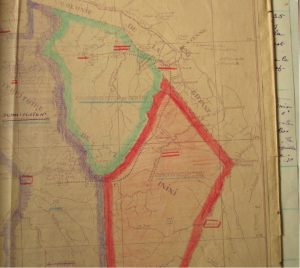

Map of French Guiana from the archives in Aix en Provence. The area encircled in green was where Lý Liễu and his fellow prisoners would have worked in their wood-cutting unit.

Due to this position, Lý could slip away from the camp and was able to go to Cayenne, the capital of French Guiana, at night to mix with the Chinese community. Indeed he was able to get medicine, non-prison clothing, and send and receive letters clandestinely.[4] Convicts were dressed in distinctive grey clothing that made escape harder; medicine was also vitally important because of the rampant diseases of the penal colony.

Tafia Dreams of Escape

Anecdotal accounts indicate that prisoners in French Guiana had two fixations to help them endure the penal colony: tafia (cheap homebrewed rum) and the hope of escape. However, escape was very difficult and dangerous. Even if the surveillance system was understaffed there were two guards always at their posts: the jungle and the sea. [5] Even if acquiring the necessities for escape was possible, trusting both your co-conspirators and a boat captain (if involved) was vital. Anthropologist Peter Redfield estimates non-returned escapees at between 2-3 percent of the prison population, but it is simply impossible to know how many prisoners successfully escaped. [6] Historian Stephen Toth simply states: “To flee was a truly remarkable feat.”[7] Or, to be more precise, “to flee successfully was a truly remarkable feat.” Maps of South America carried a huge premium. Lack of geographical knowledge made many prisoners dependent on prison rumor to understand what terrains lay around them.[8] Possible escape routes existed and “the most common was to head northeast into what was then Dutch Guiana, either through the jungle or floating on a raft.”[9] However, escaped prisoners carried a hundred franc capture award, an inducement for Amerindians in the area. Often attempts to reach Trinidad ended in death – the sea could be very rough and difficult to negotiate without skilled nautical expertise and once there it could just end in extradition by British authorities.[10]

The Chinese Connection in Cayenne

In colonial Cayenne, indeed throughout French Guiana, Chinese trading communities (many Cantonese-speaking) were intimately woven into the fabric of penal colony society. Indeed, the term “Le Chinois” came to mean “corner market” in Guyanese French. Even today in French Guiana Chinese shops are throughout the country. It was through one of these trading communities that Lý and his friends organized their escape in 1917 disguised as Chinese traders from Cayenne.[11] Racial masquerading was a skill perfected by all of them in their years traveling between Hong Kong and Vietnam. As for the British authorities in Trinidad, one Asian looked pretty much like the next Asian.

In Port of Spain, different Chinese companies employed the escapees. Lý met his English wife through his work and after they married, he was able to borrow money from his wife’s family and establish a small business. However, in 1923 he and his compatriots decided that patriotism shouldn’t be forgotten and Vietnam still needed their anti-colonial efforts. In his memoirs, Lý Liễu recalls how on that fateful day, when his wife and children were visiting her parents, he withdrew some of their joint savings and left Port of Spain.

Little is known of his precise activities over the next few years – in which he was based in southern China and Hong Kong – but in 1929, Lý Liễu decided to return to Vietnam. Ironically, this ultimately led to his re-arrest in the city of Vinh Long in southern Vietnam four years later. In 1933, a colonial tribunal found him guilty of fomenting rebellion and sentenced him to fifteen years hard labor. He died on the prison island of Poulo Condore (off the southern coast of Vietnam) shortly after his sentence, at the age of 40.

Narratives of prisoners within French penal flows can often be reconstructed from the extensive extant archives at the Centre des Archives d’Outre Mer in Aix en Provence. Lý Liễu’s is not one of them. He only makes three brief appearances in an official archive. He appears at his times of sentencing: 1913 and 1933 and he appears in the private papers of Gaston Liebert, the French consul in Hong Kong at the time of his arrest. (Liebert commented on his connections to that esteemed establishment: St Joseph’s School.) Although there are voluminous files in the French archives on French Guiana, Lý Liễu’s story also shows the lacunae of the archives and the need to read widely in different contexts in order to piece together a multi-national narrative of a very cosmopolitan prisoner.

To a Western reader, Lý Liễu’s decision to return to Hong Kong, and eventually Vietnam, marked a tragic turn in his tale that ended in his untimely death on the penal island of Poulo Condore. For the only Vietnamese historian who has written extensively about him, the real tragedy is Lý Liễu’s endlessly restless spirit. [12]The fact that his half-English, half-Vietnamese children of Trinidad were unable to place a grave in his natal village means a spirit who will never be at peace, and who will ceaselessly haunt the penal vestiges of Côn Đảo prison on the former prison island of Poulo Condore.

Notes

__________________________________________________________________

[1] Nguyễn Văn Hầu, “Lý Liễu và phong trào đại Đông Du,”[ Lý Liễu and the Study East movement] Bách Khoa CXXXXV, 39–49.

[2] This phrase is where the title of René Belenoit’s, Dry Guillotine: Fifteen Years Among the Living Dead (New York: E.P. Dutton and Company, 1938) comes from, one of the most famous memoirs of French Guiana.

[3] Peter Zinoman, The Colonial Bastille: A Social History of Imprisonment in Colonial Viet Nam 1862-1940. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001; 111, 112.

[4] Nguyễn Văn Hầu, Chí sĩ Nguyễn Quang Diệu: Một lãnh tụ trọng yếu trong phong trào Đông Du miền Nam [Revolutionary Nguyễn Quang Diệu: A Key Leader in the Đông Du Movement in Cochinchina]. Tựa của Nguyễn Hiển Lê [Preface by Nguyễn-Hiển Lê]. Sài Gòn: Xây dựng, 1964, 56.

[5] Belenoit, Dry Guillotine, 54.

[6] Peter Redfield, Space in the Tropics, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000, 80.

[7] Stephen A. Toth, Beyond Papillon: The French Overseas Penal Colonies 1854-1952, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006, 57.

[8] This comes up in various accounts of the penal colony. Belenoit, Dry Guillotine, 45 talks in detail about the difficulties of finding out geographical information.

[9] Redfield, Space in the Tropics, 80.

[10] This changed in 1931 when British authorities decided to no longer extradite prisoners from Trinidad on humanitarian grounds.

[11] Nguyễn Đình Đầu, “Nguyễn Quang Diêu: Một Kiếp Thề Ghi Với Nước Non, [Nguyễn Quang Diêu: A Lifetime of Dedication and Remembrance for the Country]”in Nhà Lao Annam ở Guyane.[The Vietnamese Prison in French Guiana.] T.P.Hồ Chí Mịnh: Nhà Xuât Bản Trẻ, 2008, 87.

[12] Nguyễn Văn Hầu, “Lý Liễu,” 49. Poulo Condore is now known as Côn Sơn island and attracts many tourists to its tropical island charms and luxury resorts.

________________________________________________________

Dr Lorraine M. Paterson has done extensive research on penal flows from French Indochina to other parts of the French empire. She acts as a member of the Advisory Board of the Carceral Archipelago Project. Her contact e-mail is: lmp20@cornell.edu.

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

Recent Comments