How can we frame convict labour in the broader context of entangled labour relations? This is one of the key-questions in the Carceral Archipelago project, which seeks to understand how (especially transported) convicts interacted with other workers within and across empires. Some important suggestions for addressing this question emerged during the first European Labour History Network (ELHN) conference, held in Turin on 14-16 December 2015.

The ELHN was created in October 2013 with the aim to enhance the cooperation among labour historians across Europe, and beyond. Its peculiarity vis-à-vis other scholarly initiatives in the field of labour history lies in the bottom-up structure, that centres on thematic working groups. The “Free and Unfree Labour” working group is one of the largest groups within the ELHN, and it was in its programme that the question of the entanglements between labour relations was explicitly addressed. Among others, the following issues were especially highlighted.

First, all participants insisted on the need to address “freedom” and “unfreedom” in labour relations dialectically. On the one hand, it is important to study the way historical actors have defined and perceived the distinction between “free” and “unfree” labour, that is, how contemporary discourses on freedom (and progress) have shaped the conceptualization of labour relations. On the other hand, scholars ought to fully acknowledge fluidity among labour relations. In other words, we should pay attention to the entanglements and combinations of chattel slavery, convict labour, wage labour, indenture work, and other labour relations, and see them all as disposed along a continuum, rather than conflate some of them with absolute freedom or unfreedom. Moreover, differentiations within each labour relation ought to be acknowledged: for example, in the study of convict labour, one should pay attention to the distinction between the function of the coerced labour of prisoners, transported convicts, and those sentenced to the galleys, and study the way each sub-type of convict labour combined with sub-types of chattel slavery (e.g. urban and plantation slavery) and wage labour (i.e. different types of wage contracts).

Global labour history (GLH) provides the most comprehensive approach to frame the function of labour relations and their sub-types. Indeed, global labour historians insist that not only wage labour, but multiple (“free” and “unfree”) labour relations participate in the process of labour commodification. The approach of GLH thus provides a vantage point for a non-Eurocentric view on the function of (sub-)types of labour relations, and their mutual combinations.

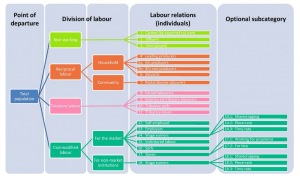

Various strategies have been envisaged so far to reach this goal. These include the taxonomy of labour relations, developed as part of the Global Collaboratory for the History of Labour Relations, the IISH-based project that seeks to “provide statistical insights into the global distribution of all types of labour relations… in five historical cross-sections: 1500, 1650, 1800, 1900, and 2000”, and to explain “signalled shifts in labour relations world-wide”.

Some scholars in the Turin sessions have explicitly referred to this taxonomy, for example in order to understand convicts’ and military convicts’ labour in Francoist Spain (Fernando Mendiola). Partly in alternative to the macro-historical approach of the taxonomy, participants have repeatedly stressed the need for full contextualisation of labour relations. In other word, they have pointed to the need to study the interaction between slavery, convict labour, indenture work, wage labour, tributary labour, and other labour relations within specific historical contexts, rather than in abstract terms. Moreover, here “contexts” may refer to specific sites, such as urban centres or rural areas, to broader yet somehow coherent regions (e.g. the Mediterranean or the Caribbean), or to specific institutions, such as the household, the plantation, the factory, the workhouses and the galleys. Within these contexts it becomes also possible to investigate the concrete ways by which historical actors defined and perceived each labour relations, their combinations, and freedom and unfreedom. Indeed, this spatial sensitiveness has arguably been the major contribution of the ELHN panels to the discussion on “free and unfree labour”, and a considerable step forward vis-à-vis previous scholarly debates in the field – see especially the contributions in T. Brass and M. van der Linden eds., Free and Unfree Labour. The Debates Continues (Peter Lang, 1997).

Another potential way forward in the debate on the entanglements between labour relations has been investigated in the sessions Early Modern Captivity: Conflicts, Interactions, and Repercussions and Precariousness and Free/Unfree Labour at Global Level: Connections and Intersections in a Long Historical Perspective. Speakers in those panels especially insisted on the need to study not only the connections among abstract labour relations, but also the practices of solidarity and conflict among workers within and across labour relations. Agency therefore stood central in these papers, as well as in some interventions in the roundtables and during the debates. Moreover, here the concept of “agency” was broadly understood to include individual and collective behaviours, daily and exceptional forms of resistance, and the workers’ influence on the decision-making processes.

The dialectic conceptualization of the “free and unfree” as distinct yet fluid in labour relations; sensitivity to spatiality in the contextualised analysis of the combination of multiple labour relations; and the need to foreground workers’ agency across multiple labour relations: these key-themes in the ELHN Free and Unfree Labour sessions resonate with, and provide new tools for, the Carceral Archipelago’s quest to “connect convict transportation to enslavement, indenture and other forms of coerced labour and migration”.

Subscribe to Christian De Vito's posts

Subscribe to Christian De Vito's posts

Recent Comments