Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this post contains images of people who have died.

At the Carceral Archipelago’s conference last month we discussed how landscapes around penal institutions could be rendered “empty” in our histories. This conception emerges from archival records in which land and sea are portrayed as “natural barriers” to secure, isolate and punish convicts. Alternatively, the natural landscape could be seen as an opportunity for convict labour to offset the costs of imprisonment. The dichotomy of a landscape that was simultaneously empty and exploitable is particularly evident on islands which, due to their bounded nature, were considered ripe for territorial appropriation, scientific observation and incarceration.

However, carceral spaces were – and remain – small parts of larger landscapes that are often richly mapped, inhabited and/or understood by Indigenous peoples. As historians, we must remain attuned to narratives that attempt to elide these complex Indigenous geographies. I will be exploring these themes in three case studies in my work on nineteenth century Australian prison islands.

The first, Melville Island (Yermalner), was inhabited by the Indigenous Tiwi when a convict settlement was established there in the 1820s. The second, Cockatoo Island (Warameah), was reconfigured as a false ‘Indigenous’ space in the 1870s, in an attempt to elide the carceral history that scarred its landscape. The third, explores how modern-day Nyoongar artists and activists are bringing pre-colonial histories of Rottnest Island (Wadjemup) into dialogue with its much shorter history as an Aboriginal prison.

Melville Island

The Tiwi Islands are situated off the Northern Territory, near modern-day Darwin. They comprise of two large islands, Melville and Bathurst Islands which are separated by a thin strait, and an archipelago of 9 smaller islands. Melville Island (Yermalner) housed convicts and soldiers on a settlement known as “Fort Dundas” between 1824 and 1828.

‘Melville and Bathurst Islands with the Cobourg Peninsula. North Australia’.

From: Major Campbell’s ‘Geographical Memoir of Melville Island and Port Essington’, Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, vol. 4 (1834)

In his instructions Captain Bremer was told to establish camp on the other side of the river, should the Tiwi prove hostile. Far from acting as natural boundaries waterways became the logical site of interaction between the Tiwi and the Europeans as they were fastest means of navigating islands that were covered in dense forests and mangrove swamps. The first meeting between the Tiwi and the Europeans took place on the 25th October 1824 on a river on Bathurst Island, at a spot which Captain Bremer renamed “Point Interview” along “Intercourse River.” This act of cartographic renaming relegated the Tiwi people to a secondary role, defined through Europeans, bolstering the idea of an ‘empty’ land that was ripe for British appropriation.

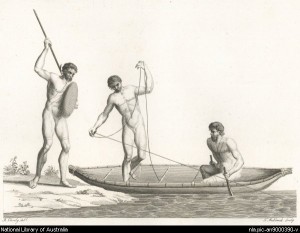

‘Interview with the natives at Luxmore Head in Melville Island’ (1818)

From: Philip King Parker’s album of drawings and engravings, 1802-1902

PXC 767, State Library of New South Wales

Despite their desire to re-map the land from a European perspective, Indigenous knowledge quickly emerged as the best means of mastering the – to European eyes – extremely hostile environment of the island. Major Campbell understood the utility of good relations with the Tiwi, when he wrote:

“I was extremely anxious to court their friendship, as without it, with our limited numbers and means, we never could become acquainted with all the resources of the island, or make them available to us.”

Despite limited interaction with Tiwi groups, Indigenous knowledge systems were used by the Europeans to survive. This was achieved by finding, what Commandant Barlow called ‘traces of natives’: in the form of abandoned camps, observations at a distance, occasional interactions and even the kidnapping of a Tiwi child. The position of Tiwi camps was used to locate likely sites of fresh water and the settlers observed which plants Tiwi people ate, which proved crucial when supply ships were scarce and scurvy rife. Thus we see how the British attempted to exist in the natural environment by observing Indigenous geographies, at the same time as they tried to elide the Tiwis’ presence ontologically.

Cockatoo Island

The astronomer William Dawes recorded that the Eora – the Aboriginal people who lived in the Sydney area – knew the largest island in Sydney Harbour as Wareamah. The Eora means the “people” and is derived from Ee (yes) and ora (here, or this place), demonstrating their close relationship to place. This relationship was dominated by water as their territory included sandstone cliffs, bays, coves, beaches, lagoons, creeks and the islands in (what is now known as) Sydney Harbour. Although Cockatoo Island was not permanently inhabited, according to oral tradition it was visited by the Wangal in bark canoes for fishing for thousands of years before European occupation.

‘Natives of Botany Bay’ by Thomas Medland and R. Cleveley

From: Philip Arthur, Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay (1789)

NK3374/3, National Library of Australia

When the British arrived in 1788 they renamed Wareamah “Cockatoo Island” after the sulphur-crested cockatoos that lived in the red gum trees covering its craggy surface. When the island became a convict stockade in 1839, the convicts began deforesting the island to make it more suitable as a carceral landscape. Without foliage to hide behind, the barren sandstone island was a more viable prospect for securing prisoners so close to the biggest settlement in the colony. After all, Cockatoo Island was separated by barely half a kilometre of water from the populated neighbourhoods of Balmain and Woolwich. After deforesting the island, the convicts continued to alter the landscape – they set to work burrowing down into the ground to build grain siloes (1839-42) and used pickaxes to quarry sandstone to build with. Convicts next began constructing a dockyard (1847-57). Explosives were used to blast out the sandstone cliffs, resulting in the distinctive ‘inverted anvil’ shape of the island today.

‘Cockatoo Island, Sydney (1856-7), by Mrs. Macpherson

From: Scenes in New South Wales

PXA 3819, State Library of New South Wales

Two years after the departure of convicts in 1869, the island was renamed once again by Europeans in an effort to obscure its connection to ‘unmodern’ convictism as they repurposed convict-built structures for a reformatory. In an act of self-reference that obscured Aboriginal ownership by wrongly alluding to it, they named the institution “Bileola” after the Kalimouri word for Cockatoo – a community that did not live along the Sydney coast. By alluding both to nature and Aboriginal culture, the Sydney authorities attempted to obscure the convict past so obviously etched into the landscape.

Rottnest

Rottnest was originally named Wadjemup by the Noongar who inhabited the south-western region of what is now known as Western Australia. This name roughly translates as ‘place across the water’, referring to the separation of the island from the land around 6000 years prior to colonization. Despite being uninhabited when the Europeans arrived, it remained an important part in the cultural geography of the Nyoongar. It was a Dutch naval commander, Willem de Vlamingh, who named the island Rottnest (Rat’s nest) in 1696 after mistaking the large numbers of quokkas (marsupials) there for rodents. The British claimed the island as their territory when they established a settlement on the mainland at Swan River in 1829. The first Nyoongar people to land on the island for 6000 years were ten prisoners in August 1838. Rottnest continued as a penal establishment for Aboriginal prisoners until 1931, incarcerating around 3700 Nyoongar men and boys. Today, every Aboriginal person alive in Western Australia has an ancestor who was incarcerated on the island.

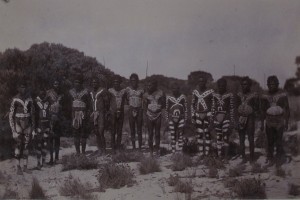

‘Aboriginal prisoners on Rottnest Island with tribal markings’

From: Col. E.F Angelo’s collection of photographs, Battye Library/State Library of WA

Recent heritage plans are interpreting the wider heritage landscape of Rottnest Island – to incorporate the 90 year history of the prison within 40,000 years of Indigenous history and culture. Since 2008, the Rottnest Island Authority has pursued Reconciliation Action Plans, which encourage the engagement of Noongar community members in heritage plans. Blaze Kwaymullina, Ambelin Kwaymullina and Sally Morgan have argued that Aboriginal heritage is not connected primarily to material objects so policymakers must move beyond a ‘museum mentality’ to include oral traditions and landscapes within heritage plans.[1] This has been reflected on Rottnest. For example, as a prison island sealed off from public access, the island was less impacted by settlement, leading it to become a natural reserve and tourist resort today. For example, quokkas that are rare elsewhere in Western Australia, due to the introduction of predators, are abundant on the island. As a result, the island is an ideal site to explore the relationship between Noongar people and the environment more generally. Visitors are also encouraged to partake of a ceremony recognising the Whadiuk as the traditional owners of the island, by reciting a phrase and letting sand drift out of ones’ hands. Yet, in an interweaving of pre-colonial and carceral histories, the instructions to do so are at the edge of the Aboriginal prisoners’ graveyard. Thus we see how the heritage plans for Rottnest situate carceral remnants within a larger landscape of Noongar history and culture.

Quokkas were mistaken for rats by Vlamingh, and were hunted by the Aboriginal prisoners on Rottnest when imprisoned there.

[1] Blaze Kwayamullina, Ambelin Kwaymullina and Sally Morgan, ‘Reform and Resistance: An Indigenous perspective on proposed changes to the Aboriginal Heritage Act 192 (WA), Indigenous Law Bulletin, 8:1 (2012), p.8

Subscribe to Katy Roscoe's posts

Subscribe to Katy Roscoe's posts

Recent Comments