By Kristin O’Brassill-Kulfan.

Over the past two years, I’ve been welcomed as an affiliated researcher by the CArchipelago team with the tangible benefit of having learned more about both convict history and global history in this brief span of time than in a lifetime previous. My own work is less internationally defined than the avenues the team has been opening up with its recent scholarship, but still decidedly hinges upon the themes of punishment, space, and mobility. In my research on the criminalization of indigent transiency in the early American republic, I’ve zeroed in on one particular physical monument to the intersection of these concepts: Philadelphia’s Arch Street Prison, a prison that held no convicts. The history of this institution demonstrates some key theoretical divisions among so-called criminal populations, illustrating that there were also physical, spatial manifestations of these ideas in their operation of punitive incarceration.

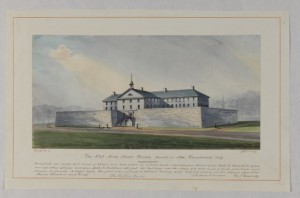

Arch Street Prison, which was used for less than three decades, was designed to hold the overflow of the city’s older Walnut Street Prison, which was by 1803 filled beyond capacity. Criminal convicts would continue to be incarcerated there, while the “denomination of prisoners for trial, vagrants, runaway or disorderly servants and apprentices, and all other descriptions of persons (except convicts)” would be held instead at Arch Street.[1] ‘Official’ state criminals would continue to be sent to the Walnut Street Prison. Construction began in 1804 and continued for several years while disputes over funding and allocations between the state, city, and prison inspectors in charge of overseeing penal facilities muddled the process and, records indicate, the structure itself. Sometime around 1816, Arch Street began to receive the first arrivals of the inmates it was designed to confine: vagrants, debtors, and untried prisoners.

Over the next twenty years, many of the disorderly and destitute of the Philadelphia region were incarcerated in this facility, which was essentially a bridewell that some accounts claim was “never considered sufficiently safe or well constructed to house prisoners.”[2] For the two thirds of Arch Street’s inmates who had arrived there following a vagrancy conviction, the punishment of incarceration in this institution was usually for some form of movement or mobility. Over a thousand persons were sentenced to serve time there each year for the crimes of ‘strolling’ and ‘wandering,’ being persons ‘having no residence,’ and ‘being destitute of a home.’ This mobility and general lack of stability not only prompted their arrest and punishment, but was also used to demarcate the level of comfort and provisions due such persons while incarcerated.

Arch Street Prison contained a separate apartment to confine debtors, while in the rest of the prison, an annual average 2,000 of “vagrants and untried prisoners, of all colors and all degrees of crime” were “assembled in one common room” where they formed “one common association,” and “the reputed pirate and murderer” might be found “seated beside a youth confined for a drunken brawl.”[3] Legislators and reformers had condemned this intermingling at Arch Street’s predecessor facilities, and the prisoners’ shared confinement in space contributed to calls for a separate system that might not breed, as it was feared, further crime. And yet, strong distinctions were drawn by authorities between criminal convicts and Arch Street’s non-criminal prisoners, who claimed that convicts held in Philadelphia’s high profile Eastern State Penitentiary were “of a different class,” possessing “higher intelligence,” better social habits, and better hygiene than the average “miserable vagrant” confined in the Arch Street Prison. [4] The conditions in the two institutions reflected this perception. In 1824, a Philadelphia Grand Jury found that “the arrangements made for the safety and health of the convicts [at Walnut Street Prison] are as well calculated for those objects as the extreme scarcity of room in the…apartments of the vagrants and untried prisoners.” Discomfort was a design feature for the punishment and housing of vagrants and debtors as a deterrent against recidivism, yet the Grand Jury asserted that the “privations so great” which they endured were a “severe punishment for their misfortunes and poverty.”[5] A legislative committee investigating the issue in 1833 questioned whether offering greater “provisions and comforts” to incarcerated vagrants would encourage “idleness and profligacy,” yet asserted that they were entitled to be treated at “least upon an equal position with the convicts.”[6] Incarcerated in penal facilities with worse conditions than those endured by convicts and yet not considered actual criminals by the state, vagrants and debtors occupied a unique position in the early nineteenth century United States system of crime and punishment.

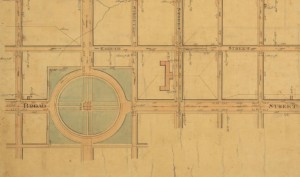

Arch Street was located in the city arguably at the very heart of debates about American penal reform. The historiography of punishment has cast the experiments in solitary confinement undertaken at Eastern State Penitentiary as a focal point for understanding the gradual trajectory toward modern systems of punishment, and even the inevitability of abolishing imprisonment for debt. The separate system was constructed primarily to place physical space between prisoners in a direct rebuttal to the lack of space between prisoners in Walnut and Arch Street Prisons, barely a mile away across the city. While it was the conditions at these two prisons that prompted reform, the decades of concurrence in the Jacksonian era while these institutions continued to exist side by side because the realities of the size of the population ‘requiring’ incarceration forced practicality to the fore, rather than leading to swift replacement of the old facilities, are often overlooked.

During this time, likely under the influence of debates over separate confinement, the considerations of spatiality within the ‘Old Arch Street Prison,’ as it was referred, became paramount. The prison was segregated by sex in addition to level of criminality, with the debtors separated from vagrants and those awaiting criminal trials. When cholera struck Philadelphia in 1832 and Arch Street saw the highest mortality rate in the entire city, commentators reported deaths at the prison by their spatial location even over sex, noting that on one day alone, “about twenty-two died on the women’s side, and upwards of fifty in the men’s department.” Divisions both theoretically penal and physical marked the management of disorderly and criminal behaviour in Philadelphia, punishments “dealt out,” as one observer noted, “not to convicts, but to men whom the law holds as innocent, they not having received a trial by a jury of their peers” and to vagrants, men and women alike.[1] By 1837, the prison’s short-lived function as a vagrant prison was trumped by plans for new facilities, and Arch Street was demolished. Convictions and incarceration, even in a prison without convicts, revealed contemporary beliefs about the moral degradations brought on by poverty and the physical, spatial solutions authorities used to limit their impact on the wider community.

[1] A Tale of Horror! Giving an Authentic Account of the Dreadful Scenes that took place in the Arch Street Prison (Philadelphia, 1832).

[1] “Sale of Walnut Street Prison,” Hazard’s Register of Pennsylvania, vol. 7, 1831.

[2] Manuscript collection description, Arch Street Prison minutes, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, http://discover.hsp.org/Record/ead-Am.3228.

[3] Annual Report of the Board of Managers of the Prison Discipline Society, vol. 5, 1830.

[4] Philadelphia Inquirer, November 9, 1832.

[5] Annual Report of the Board of Managers of the Prison Discipline Society, vol. 5, 1830.

[6] “On the apartment for Criminals and untried Prisoners in the Arch Street Jail,” Hazard’s Register of Pennsylvania, vol. xi, no. 12, 1833.

Kristin O’Brassill-Kulfan is completing her PhD in History at the University of Leicester, and is an affiliated researcher on the Carceral Archipelago project. She holds an MA in Modern History from Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland and BAs in History and English from Millersville University in the US. Her research explores vagrancy, pauper migration, and other forms of indigent transiency in the early nineteenth century US in the contexts of the law, state control, and corporeal experience.

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.