The Kamikawa region is one of areas that today still has relatively a large population of the Ainu. It is also the site of the most famous land dispute between the Hokkaido Government and the Ainu in the early 20th century. The Hokkaido Aborigines Protection Act of 1899, containing some restrictions and leading to many problems, first acknowledged the land ownership of the Ainu. However, this law was not applied in the Kamikawa region and the Ainu had to carry on a 30-year dispute to obtain their land rights in this area. In Japanese historical scholarship, Ainu issues and central prisons are seldom linked. However, the rapid development of Kamikawa, which threatened Ainu livelihoods and land rights, could not have been accomplished without convict labour.

In 1881, Hokkaido was divided into three prefectures adopted following the mainland’s administration system. However it did not work, and was abolished in 1886 when the Hokkaido Government was established. This government followed the general model in British colonies and handled legislation, administration, police and armed forces (Kaneko 1885). Three central prisons in Hokkaido also came under control of the Director General of the Hokkaido Government, and from 1889 Directors of central prisons held the title of the headman of neighboring counties. For instance, the director of the Kabato prison was also a headman of three counties; Kabato, Uryu and Kamikawa. Thus the prison, in corporation with the Hokkaido Government, offered a convict labour force to development projects in these counties. Construction of a road to Asahikawa was begun in 1886, and completed in 1889. From 1888 to 1892, Tondenhei (soldiers for developing and guarding Hokkaido) villages were constructed along the road that was eventually incorporated into the 7th division of the Japanese army stationed in Asahikawa since 1900. In 1898, the railroad reached Asahikawa. The result was a rapid population increase in Kamikawa county.

Figure 1: Kabato, Uryu and Kamikawa Counties

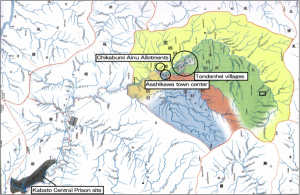

Figure 2: Kamikawa County in 1892 (Asahikawashi 2002)

Kamikawa county is located in inland Hokkaido. Even in 1889, 20 years since Hokkaido’s incorporation into Japan, it had only 18 ethnic Japanese, whilst the Ainu population was 199 (Hokkaido 1891). In 1898, its population grew to about 30,000. In 1902, Asahikawa (in Kamikawa county), with a population of 16,441, became the 5th largest city in Hokkaido, after Sapporo, Otaru, Hakodate and Esashi (Asahikawashi 2002). Other than Sapporo, the capital of Hokkaido, the three largest cities in the country are located on the sea coast, and they were ex-trading posts as well as fishery bases dating from the early modern period. Thus, Asahikawa was the second largest inland city next to Sapporo.

One of issues with which the Hokkaido Government was engaged was the development of the inland areas and enlargement of the immigrants’ population. For these purposes, in 1886 they began to survey land and divide it into sections which were later loaned to immigrants. This project involved relocation of Ainu villages which were scattered along the rivers. Traditionally, the Ainu lived in small villages with up to 20 households, with the exception of seacoast settlements where had larger populations gathered together and worked as labourers for the Japanese commercial fishery. However, to create parcels of land for Japanese farmers, these small Ainu villages were consolidated. The first case occurred in the Kabato county in 1889, the second in the Kamikawa county in 1891. Regarding Kamikawa, Chikabumi district in present Asahikawa was set aside as Ainu provisional allotments. This relocation, however, did not seem to have been forced.

Ainu woman Kura Sunazawa (1887-1990), in her autobiography, mentions this removal in relation to the way their world changed with the coming of convicts (Sunazawa 1983:40-41). Her grandfather, Monokute, was a leader of the Kamikawa Ainu. He moved from his home in Nagayama to the Chikabumi allotments. He explained that it was because convicts came and awful things began to happen. Kura writes that, because of hard labour, murders of warders by convicts, of convicts by warders, or of convicts by convicts often seemed to have happened. Nagayama was the place where the first Tondenhei village in Kamikawa was established in 1891. The road to this area was completed by 1889. Both projects were done by convict labour.

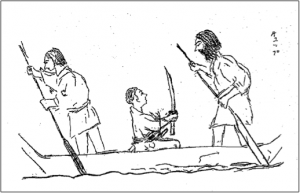

One of Monokute’s experiences was as follows. One day in early spring, one escaped convict came to him. Showing a sword, the convict threatened him to make Monokute take him across the river by boat. Monokute thought whether or not he took the convict, he would be murdered. Taking with him another young Ainu man, Monokute sailed a boat off the bank. Before they reached the other side, Monokute spoke to the young man in the Ainu language and told him to jump off to the bank when Monokute shouted, then he would push the convict into the river and hit him to death with a paddle. When Monokute shouted he stepped hard on one side of the boat. It tilted and the convict fell into the river and died. Afterwards, Monokute received a reward from a government official, as the convict had murdered a warder, stolen his sword and run away.

Figure 3: Drawing by K. Sunazawa. The man in the right is her grandfather. The man in the center with a sword is a convict. On the left is the young Ainu man (Sunazawa 1983:41).

Kura also mentions another episode; her relative witnessed the exercise of the punishment called nokohiki (it literally means sawing). This was one of the punishments in early modern Japan and it was abolished by the Meiji Restoration Government. One day, an Ainu woman saw a convict tied to a pillar by a bridge. A saw was tied to his neck to saw his neck whenever someone crossed the bridge. It was said that this convict murdered another convict.

Actually, nokohiki was an additional punishment to the death penalty in the early modern period. A criminal is tied in the public space, with a bamboo saw placed next to him that a passerby could use to saw his neck. However, it is said that this was just a display, and there was a guard to prevent someone actually doing it. Execution was done afterwards at an execution site (Ishii 2013:64-68). It is unclear whether the nokohiki which Kura heard of is the same as early modern punishment. However, the Ainu seemed to take it seriously, and there may be enough reason for them to believe so, as they witnessed many awful incidents by both convicts and warders.

After moving to the Chikabumi allotments, the Ainu faced another awful situation caused this time by Japanese settlers. As the area was close to the town center, the price of the land was increasing. Japanese capitalists and settlers, conspiring with the Hokkaido government, attempted to remove the Ainu from Chikabumi. After a dispute lasting 30 years , the Ainu gained their ownership to a part of the land which was reserved for them in 1891. The rest of it was lost forever. Convict labour made possible incredibly rapid increase of population and changed values of Ainu land. To the Ainu its process was too inhuman in multiple ways.

Dr Minako Sakata is a researcher in the Carceral Archipelago project, and a research associate of the Department of Area Studies, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the University of Tokyo. Her research field is indigenous studies, especially focusing on ethnohistory and oral tradition studies of the Ainu in Japan.

References

Asahikawashi. 2002. Shin Asahikawashishi, 2.

Hokkaido ed. 1891. Hokkaidocho dai 4 kai tokeisho.

Ishii, Ryosuke. 2013. Edo no keibatsu. Tokyo: Yoshikawa kobunkan.

Kaneko, Kentaro. 1885. ‘Hokkaido sanken junshi fukumeisho.’ In Hokkaido ed. 1936. Shinsen Hokkaidoshi. pp. 591-644.

Sunazawa, Kura. 1983. Ku sukup oruspe: watashi no ichidai no hanashi. Sapporo: Hokkaido shinbunsha.

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Subscribe to Emma Battell Lowman's posts

Recent Comments