I have had the privilege to visit Australia for the past two months on a research trip thanks to the generous funding of the Menzies Centre for Australian Studies. I’m now a little halfway through my trip and have visited all but one convict sites where large numbers of ‘my’ convict subjects stayed or passed through in four different states (New South Wales, Tasmania, Queensland, Western Australia). I can now understand how easily Cockatoo Island’s convicts would have seen people going about their business in Balmain. I can now imagine how isolated a peninsula can feel (just as much as an island) after passing through the narrow Eagle’s neck to Port Arthur. More noticeably, everywhere I look, and when I’m not expecting it, the legacies of the hard work of convict labour are there in the infrastructure of bridges and buildings that survive to this day. And I can’t help but notice how the plaques that mark them continue to anonymise the workers, and give credit to those who worked them.

Richmond Bridge (Tasmania) – the plaque credits ‘convict labour’ but it is the commissioner, the engineer and the stonemason who are named.

Of the many convict heritage sites I’ve visited two experiences in particular stand out – both in Tasmania in scenarios where I interacted actively with the environment or people within it. (and both, interestingly, UNESCO world heritage sites)

No amount of reading could prepare me for the feeling that the floor and walls were all the wrong way up, and the nausea that followed (and was slow to abate) in the utter-darkness of the refractory cell at Port Arthur. Even with prior warning, I could not account for the panic that rose up rapidly even as I could hear the voices of my friends (faintly) on the other side of the thick wooden door.

At the Cascades Female Factory in Hobart I took part in an interactive performance called Her Story, which tells the tale of Mary James (not her real name). Having read many analyses of convict agency, I was surprised by the strength of my own fear when I was silently appraised by a potential ‘master’ for assignment. In that moment I tensed up and felt uncertain of even where to look. My later reluctance to volunteer to report the warder for cruelty towards the protagonist of the story, in the face of no actual reprisal showed me that I would probably not have been one of the convicts who ‘stands’ out from the archive (as heroic, or resistant, or both) – rather, I’d probably slip away into the margins.

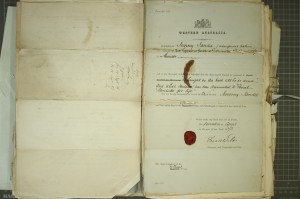

And it is this – the way in which the extraordinary stand out of the archive, and the rest can seem to blur together – that confronts me when I’m in the archive rather than in those spaces where convicts lived (and died). After all, much of my time in the archive is spent mindlessly photographing to build up a digital archive for when I get back to the UK. I often catch myself – in my bid to complete my work – depersonalising the convicts just as the imperial records had done – with whatever transportation register, warrant or deposition I’m looking at becoming not the story of a person, but another number to process. Thus these people – with their full lives and countless stories –are diminished into insubstantial versions of themselves, or worse amalgamate into a mass. When I catch myself doing this, I take the time to read this page and try to imagine – but in reality, it is not until I get home, that I can give these stories the time they deserve. As a result, I sometimes feel like Prometheus trying to breathe life into the subjects I see, while they remain curiously faceless.

I would love to hear about your experiences of finding (or not finding) historical subjecthood in heritage sites and in the archives – so please comment below or tweet @katwee.

Subscribe to Katy Roscoe's posts

Subscribe to Katy Roscoe's posts

Recent Comments