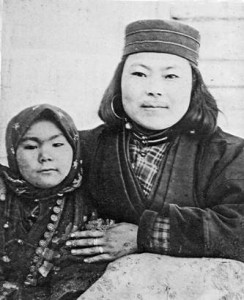

Chufsamma and son. Photographer B. Pilsudski, 1903/1904. (From: The Collected Works of Bronislaw Pilsudski. Vol. 3. Materials for the Study of the Ainu Language and Folklore 2. Plate CCLXV)

In my research on the penal colony of Sakhalin, I recently stumbled across two photographs I found to be particularly interesting. Both are images of indigenous women who lived in the eastern Russian empire during the late nineteenth century. Although the photographs hint that the women’s lives were vastly dissimilar, both represent an indigenous response to the unfolding Russian empire. For this reason, the photographs resonate with each other, variations of a similar theme. These images, and the experiences they allude to, have led me to muse more deeply on some of the wider issues and limitations of historiography, as well as the complexities associated with the representation and assimilation of indigenous women.

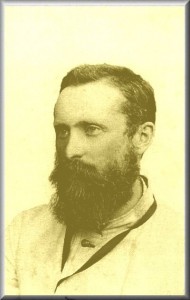

The woman in the first photograph is Chufsamma, an ethnic Ainu who lived within the boundaries of the Russian penal colony on Sakhalin Island that existed between 1858-1905. As was the case with many Ainu—as well as Nivkh and Orok—Chufsamma’s life became intertwined with those of the prisoners and exiles.[1] In 1902, she became the wife of a political exile, Bronislaw Pilsudski, who served a fifteen-year term on Sakhalin for his participation in the 1887 assassination attempt on the life of Tsar Alexander III. (His brother, Jozef, had also been involved in the attempt, was sentenced to political exile in Siberia. In 1918 he became the first president of the independent Polish state.)

Pilsudski’s life on Sakhalin as an exile—as opposed to a hard labour convict—allowed him both mobility and opportunities to participate in various activities. He worked as a lumberjack, a prison clerk, a cabinet-maker, and established a meteorological station before devoting himself to full-time ethnographic research of Chufsamma’s tribe, the Ainu.[2] It was during his extensive fieldwork among the Ainu that Bronislaw met Chufsamma and, in 1902, the two wed in accordance with Ainu customs and rituals. She was eighteen and he was thirty.[3]

Because of her marriage to Pilsudski, who by the turn of the century had achieved some local fame as an intellectual and an ethnographer, Chufsamma became increasingly comfortable with European cultural contexts. She studied some Russian and aided Pilsudski in establishing the first school on Sakhalin for Ainu children and adults. The couple had two children, the first of whom is seated beside Chufsamma in the photo.r

Circumstances surrounding the Russo-Japanese War, however, came to alter Chufsamma’s life permanently. Pilsudski recognized the Russo-Japanese War as an opportunity to both preserve his work and vacate the Russian Far East; however, his repeated petitions to Chufsamma’s father requesting permission to move with his young family from Sakhalin were categorically denied.[4] In 1905, Pilsudski traveled alone to Japan and from there to the United States before returning to his native Poland with his research.[5] Pilsudski’s work was then marginalized and forgotten, upstaged by the political tides of World War I and the Russian Revolution. It is only since the 1980s that his work has been rediscovered, causing him to attain considerable posthumous status.[6] A mountain on Sakhalin has been named for Pilsudski and a stone memorial erected in his memory. Today, Pilsudski is considered to be one of the first Russian ethnographers.

Pilsudski’s work was forgotten for seven decades before its rediscovery; Chufsamma’s life, however, remains almost absent from known historical narrative. Brief references concerning her marriage to Pilsudski can be found in a few Japanese newspaper articles and obscure Russian archival documents. Apart from these scattered references, however, the trail has gone cold.

I have wondered, as I consider her photo, about the reasons why Chufsamma, and innumerable other notable indigenous women like her, have all but disappeared from historical record. As I research the lived experiences of indigenous women within the expanding Russian Empire, I hunt for clues that might illuminate the ways in which such individuals interpreted the interplay between their own ethnic identities and tsarist colonization. To the framers of Russia’s eastern expansion, indigenous groups were useful as payers of tribute and as sources of frontier “wives.” An added dimension to these issues, however, questions related to indigenous women in particular. What means or sources remain whereby we might approach understanding the lives of of those who, like Chufsamma, were for a tenuous moment caught up in the currents of global history and colonization? Brower and Lazzerini write of a need to listen for “authentic voices from below and on the margins, indigenous ethnographers who could act as cultural mediators of a different kind” instead of accepting at face value “innocently self-generated, neocolonial assumptions that, for all their sympathy, reduced the subjects’ involvement in the making of history to a shadow of its logical extent.” [7] In his evaluation of acclaimed Russian historian Boris Mirnov’s “magisterial,” two-volume work, A Social History of Russia, Willard Sunderland wonders why a “comprehensive” history that addresses issues concerning Russia’s “multi-ethnic and multi-confessional” state has not yet been written.[8]

But, to conclude Chufsamma’s story, as much as the narrative allows us to: Pilsudski never reunited with his family, immobilized in Europe by multi-national conflict and sheer geographical distance. His body was found in the Seine in 1918.[9] Although definitive proof has not been found, Pilsudski is thought to have committed suicide. Chufsamma lived in a Soviet settlement for the Ainu in southern Sakhalin until her death in 1946. Their grandchildren now live in Japan.

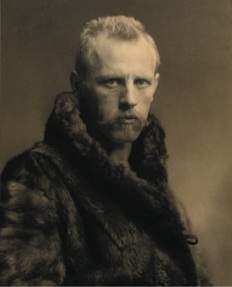

The second photograph that I reference was taken by the Norwegian explorer-diplomat, Fridtjof Nansen. In 1905, Nansen had the opportunity to study exile and indigenous settlements in Siberia as he traveled down the Yenisei River. At one point in his journey, Nansen paused his boat, mid-river, in order to photograph three Ket women living in tents on the embankment. His account reads that, midway through the session, “a fourth woman came up, carrying a child,” who desired that her photograph also be taken. As Nansen raised his camera, however, she paused and then hurried back into her tent, as if to retrieve something forgotten. When she reappeared, he saw that she had removed her traditional Ket dress and was “rigged out in shabby Russian clothes, with a handkerchief over her head. Now she was ready to be photographed; but we would rather have had her as she was before.”[10]

Like Pilsudski among the Ainu, Nansen’s desire was to record the woman on the riverbank “as she was.” Yet, even as he raised his camera, she changed. His presence on the river had altered not only the historical context of the scene but also the subject herself.

Note: I would like to express my gratitude to Sergey A. Sergeyev, Russian journalist and Radio Warsaw 1987 diploma laureate, for his assistance in verifying archival information connected with the life of B. Pilsudski.

___________________________________

[1] Forsyth, James. A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia’s North Asian Colony 1581-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1992): 218.

[2] Kan, Sergei. “Pilsudski’s Legacy Rediscovered.” Arctic Anthropology, Volume 42.2, (2005): 95.

[3] Fumio, Nonaka. “Pochemy Plachet Slepaia Staruha-Menoko iz Sela Sirohama.” http://www.icrap.org/ru/fumio12-1.html. Accessed 18.04.2014.

[4] Majewicz, Alfred F. “Bronislaw Pilsudski’s Heritage and Lithuania.” Acta Orientalia Vilenensia, 10.1-2 (2009): 75. Chufsamma’s father was concerned that she would become estranged from her culture if she left.

[5] Majewicz, 75.

[6] Kan, 95.

[7] Brower, Daniel R. and Lazzerini, Edward J. Russia’s Orient: Imperial Borderlands and Peoples, 1700-1917. Indiana University Press. (1997): xiv.

[8] Sunderland, Willard. “Empire in Mirnov’s Sotsial’naia Istoriia Rossii.” Slavic Review 60.3 (2001): 571.

[9] Kan, 96.

[10] Nansen, Fridtjof. Through Siberia, the Land of the Future. London: William Heineman (1914): 199.

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

I have never seen Chufsamma’s face. Thank you for your report.

Last year, I edited an autobiography of Sakhalin Ainu 82 years old woman.

She wrote how she treated in Japan empire era, Soviet rule, and post war Japan.

I hope to read your essay more and more.

HASHIDA Yoshinori

Staff writer, Kyodo News Service

P.S. I made a link to your report in my facebook page.

Hashida, thank you for your kind comment. I look forward to reading your book–I believe that I just found it on Amazon!

Kind regards, Carrie Crockett