Over the last few centuries women’s place in the world has changed significantly, and with International Women’s Day today it is great to see how the position of women, especially in the world of work, has changed since the first International Women’s Day in 1908.

The East Midland Oral History Archives hold over 400 interviews conducted with residents of Leicestershire by the Leicester Oral History Archive in the 1980s. A majority of these interviews have recently been uploaded to Special collections Online. They cover a wide range of topics from the late 19th to the 20th century, providing a great insight into the lives of many different groups of people, including that of women and their experiences in the world of work. The three main areas of work that are discussed during these interviews are domestic service, factory work and healthcare.

Domestic Service

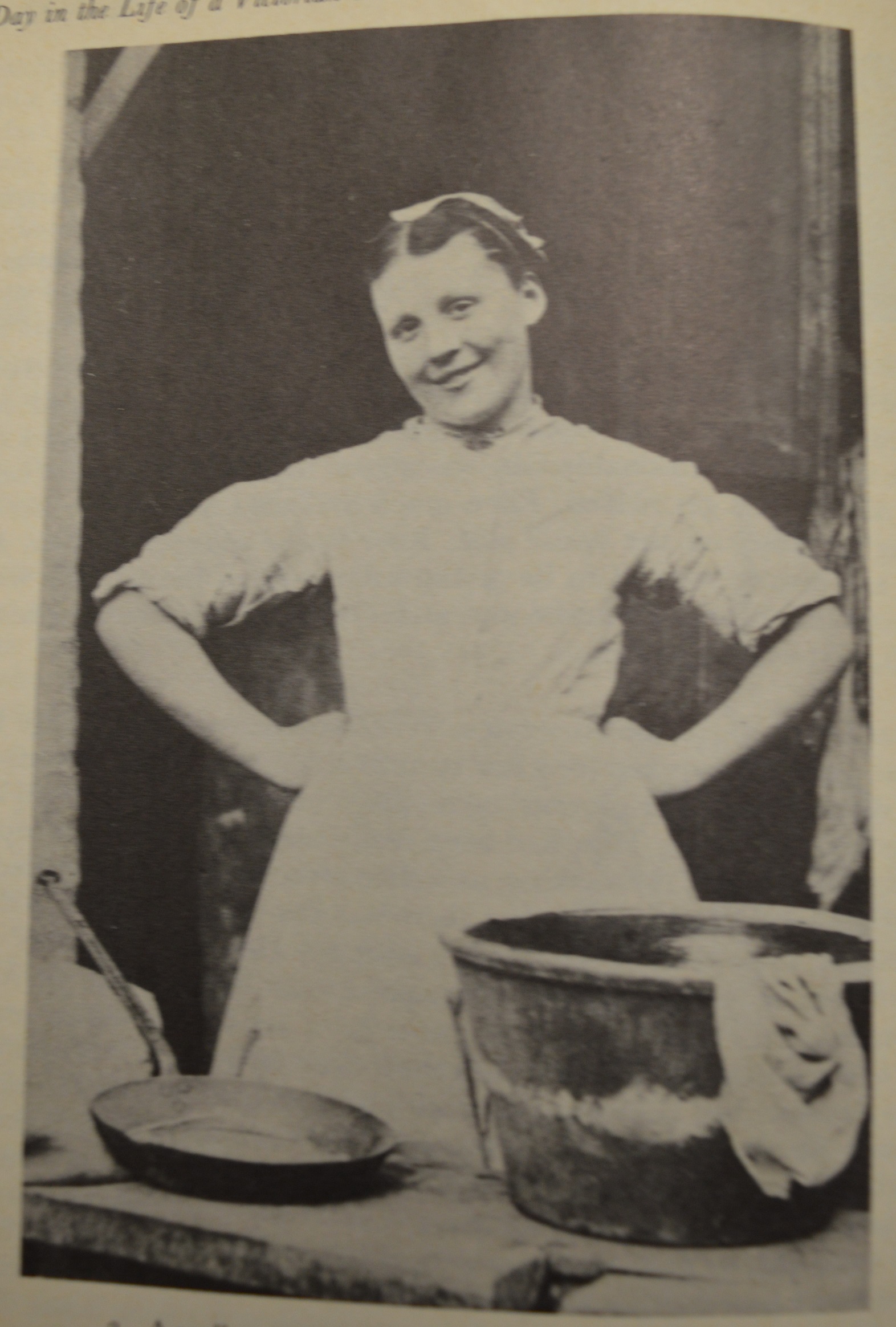

During the Victorian and Edwardian eras domestic service was one of the largest areas of work for women. According to the 1851 census around 40% of female occupations were in the domestic service sector (Huddson, 2011). But why was service “the general thing for girls to do at that time” (Elsie Dorman)? Firstly, during the Victorian era there was a tax on male servants, meaning that it was far cheaper to employ women (Clarke, 2013). Sadly this did mean that the women who were in domestic service often got paid very little, for example in an interview with Elsie Dorman she talks about getting paid 4 shillings a week, which is the equivalent to around £4.30 a week in today’s money, which I think we can all agree would not be easy to live on.

Not only were women in domestic service paid badly, but like Daisy Houghton and her sister some women would also end up in debt with their employers. Daisy and her sister ended up trapped by their employers as they tried to pay them back for the uniforms they wore. Overall, Daisy had a very bad experience within domestic service, with her employer underpaying, and underfeeding her and her sister. For many women this was what domestic service was like and “mistreatment of servants was commonplace” (Clarke, 2013, P7).

So what did work within the domestic service entail? There were many different jobs that can come under the heading of domestic service, but one of the most common roles was that of a Scullery or Between Maid. Olive Wright was in domestic service for 15 years and carried out many different roles. Olive provides a great insight into some of the typical tasks carried out, including lighting fires, making breakfast, serving meals and different day to day tasks. Olive talks about having different days dedicated to certain jobs, for example, “Mondays would be wash days,” this meant that there was always a lot of work and as Olive mentions “you always had something to do.”

Hosiery Industry

Another big area of work in the 1900s for women was factory work. For Leicester in particular this was in the hosiery and shoemaking industries. The hosiery industry was established within Leicester during the 18th century and “from this time it expanded rapidly to become the staple trade, and Leicester soon ranked as one of the major hosiery towns in the kingdom” (Head, 1961, p45). So much so that in 1951 10,509 men and 20,698 women over the age of 15 worked in the textiles industry (Census of England and Wales, 1951). For many women factory work was the only alternative to working in the domestic service.

Joan Mary Geary worked in the hosiery industry from the age of 14. In her interview she mentioned working from 8am to 6pm during the week and then from 8am to 12pm on a Saturday, for 7s and 6d a week, which roughly coverts to £13.87 in today’s money. This may be a lot better than the wages Elsie Dorman got in the domestic service, but this is still not a lot to live on.

Prior to the First World War “the textile industry had been the largest industrial employer of women,” mainly into unskilled jobs. But during the war many women moved into higher skilled roles as the men went off to fight. This gave the women the opportunity to show that they could do the same jobs as men. Despite this, many women were still seen as being less skilled than men, and therefore were paid less than their male colleagues. This problem can easily be argued to still be present today. It was not till the Equal Pay Act in 1970 that, by law, women had to be paid the same as men in the same jobs. However this didn’t fix things for women, Joan Mary Geary talks about how after the equal pay act was introduced and employers had “to pay the women full pay to the men they sort of dropped the women gradually off the men’s jobs” and back into the more unskilled jobs, therefore still meaning that women were being paid less than their male colleagues.

Health Care

The Health Care Sector was a huge employer of women. Although there were a large number of women in the medical sector during the early 1900s, it was very much a male dominated area. Just like in the hosiery industry men and women were seen to be best suited towards certain jobs, with men being doctors and surgeons and women being nurses and midwives. The 19th century brought about the start of modern medicine, and with this the professionalization of medicine. The medical profession at this time was very male dominated and “women were excluded from undertaking the university medical training that was required to practise” (Bull, 2015). In 1859 Elizabeth Blackwell became the first female doctor within the UK and by 1911 there were 495 registered female doctors in England and Wales (Wellcome Trust, 2013) and this number has grown seen then.

As mentioned above the two main roles women went into were that of nurses or midwives. Both Frances Jessie Stonely and Joan Elizabeth Robson trained to be a nurse at the Leicester General Hospital. In an interview with Joan she talks about having to do a three year course and then one year working for the hospital “on the cheap.” Whilst on the ward there was a significant hierarchy, with trainee nurses at the bottom, and according to Joan “you all had your different jobs to do.” This goes along with the idea above of men and women having different jobs.

The uniforms worn by nurses in the 1900s is a lot different to the uniforms worn today. Frances trained as a nurse in 1933. She talks about wearing “striped dresses, aprons with round bibs and we had what we called, fly away caps… stiff belts, cuffs and collars.” Wearing a nurse’s cap was one way in which the hierarchy was enforced, as nurses, sisters and matrons all wore different types of caps. Women in more senior positions, such as the matron would wear longer and frillier caps to identify their position within the hospital

It was quite common for women to also train as a midwife after completing nursing training. Midwifery is a role in the medical profession that has always been seen as a women’s role and I would say this is still debated today. Mrs G Matthews was a midwife in 1932, at this time the majority of women would give birth at home, this meant that some of the conditions at the births were not what you would have expected today. Mrs Matthews talks about one birth in particular where she “delivered a baby with three candles on the shelf and that was just before it got dark.” But lighting wasn’t the only problem at this birth, there was also the problem of bugs and fleas. Mrs Matthews recalls visiting the women after the birth and “she was covered in flea bites and so was the baby, you couldn’t see the baby for flea bites.” I’m sure it’s not just me who finds this very shocking and far from the conditions expected today.

How has it changed?

Just from looking at these three professions you can see how a women’s place in the world of work as change during the last few decades. According to the Office of National Statistics (2017) more women are currently employed than were in the past, with approximately 69.9% of women aged 16 to 65 in some form of employment in November 2016. The biggest change can be seen in health care and medical professions, where there are now significantly more female doctors and surgeons, and also far more male nurses in hospitals today.

Due to acts such as the equal pay act in 1970 and the latest Equality act in 2010, the world of work is a far fairer place for women than it once was. As mentioned above simply put one thing these acts mean is that women and men legally have to be paid the same wage for the same job. This doesn’t mean there are no longer problems, such as the glass ceiling and the fact that women end up in part-time and lower paying jobs in the first place. But overall I personally would say that opportunities for women in work have got better and hopefully will continue to improve in the coming years.

References

- Bull, M. (2015). Women in medicine: historical perspectives and recent trends. [Online]. Available at https://academic.oup.com/bmb/article/114/1/5/246075/Women-in-medicine-historical-perspectives-and.

- Census 1951, England and Wales: Industry Tables (London, HMSO, 1957), pp. 48-50.

- Clarke, K. (2013). Bad Companions: Six London Murderesses Who Shocked the World, The History Press: Gloucestershire.

- Head, P., 1961. Putting Out in the Leicester Hosiery Industry in the Middle of the Nineteenth Century’. Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological Society, 37, pp.44-59.

- Huddson, P. (2011). Women’s Work. [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/womens_work_01.shtml.

- Interview with Daisy Houghton. http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15407coll1/id/82/rec/1. LO/143/094

- Interview with Elsie Dorman. http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15407coll1/id/120/rec/2. LO/198/149

- Interview with Frances Jessie Stonely. http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15407coll1/id/151/rec/1. LO/525/475.

- Interview with Mrs G Matthews. http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15407coll1/id/8/rec/2. LO/050/001.

- Interview with Joan Elizabeth Robson. http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15407coll1/id/147/rec/6. LO/516/466.

- Interview with Joan Mary Geary. http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15407coll1/id/263/rec/7. LO/396/320.

- Interview with Olive Wright. http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15407coll1/id/110/rec/4. LO/186/137

- Office for National Statistics. (2017). UK Labour Market: Jan 2017. [Online]. Available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/jan2017.

- Wellcome Trust. (2013). Elizabeth Blackwell: the first women to qualify as a doctor in America. [Online]. Available at https://blog.wellcome.ac.uk/2013/07/22/elizabeth-blackwell/.

Images

- Munby, A, J. (1870). A scullery maid. In Davidoff, L. Hawthorn, R. (1976). A day in the Life of a Victorian Domestic Servant. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- LMA/1/4/I/5, Women working at the British United Shoe Machinery.

- LMA, Nurse, 1959.

- LMA, Nurses working on the ward, 1967

Subscribe to rwatson's posts

Subscribe to rwatson's posts

Recent Comments