In previous blogs, I have explored some of the circulations and connections that linked nations, colonies and empires, and wove together practices of punishment and penal labour across polities and imperial spaces. This included the sharing of official reports, the spread and adaptation of particular modes of convict punishment, and the intra-colonial mobility of personnel charged with the management of convicts – as well as slaves. As I have suggested, there were multiple layers of interaction between transportation and enslavement. Most recently, I have been interested in the ways in which penal colonies created new legal and discursive spaces that transcended national contexts. These include, for instance, inter-imperial discussions of the merits or otherwise of penal colonies as a means of colonization and rehabilitation, and imperial responses to the escape of convicts from one jurisdiction into another. The latter seems to offer the hope of gleaning convict perspective and experience from the archives, and in so doing of producing a new kind of global history from below.

In this blog, I will write about another – quite different – element of convict-centred circulation and connection that has emerged from my multi-sited approach to the history of penal colonies. That is the role that convicts played in colonial collecting and the production of knowledge about the natural world. When I began my project, I was almost certain that in the archives I would find what I have called a politics of comparison about prisons, penal settlements and colonies, and their intersections with other forms of coercion and unfree labour. I had not anticipated that I would find that across contexts convicts played a role in imperial exploration and specimen gathering. But as patterns are beginning to emerge from the material that I have been reading, I have realised that one of the interesting things about penal colonies from a history of science perspective is that they were often located in uninhabited or sparsely populated, pristine spaces; places rich in flora and fauna – plants, flowers, trees, small mammals, birds and insects – as well as shells and rocks. After colonization, many received repeat visits from naturalists, botanists, geologists and zoologists.

Indeed, perhaps the most famous scientist of all during this period, Charles Darwin, stopped at Mauritius, New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) during his round the world Beagle voyage in the 1830s (as well as in various Latin American sites that had prior histories of or were to have later histories of penal confinement). At the time, all three were penal settlements: Mauritius took convicts from British India and Ceylon, and British, Irish and imperially convicted convicts were sent to the Australian colonies. In Darwin’s papers we find interesting remarks about convicts, punishment and penal labour, as well as (and in the context of his metropolitan social and political networks and connections) the relationship between transportation and enslavement, and convicts and slaves.

Conrad Martens, Ruins on the North Side of Port Desire Harbour in Patagonia, Argentina. Martens drew several paintings while on board The Beagle. At the end of the C19th, the Ushuaia penal colony was established in Patagonia.

Beyond these remarks, more fascinating still is that in Mauritius, Australia and a whole host of other locations, other scientists used convicts as assistants – in clearing paths and carrying baggage, and in the collection and preparation of specimens and samples. In many instances scientists drew on convicts’ superior local knowledge, and relied upon them to a degree that is currently underplayed in the history of science literature.

This brings me to William Hooker, who was a lifelong friend and correspondent of Charles Darwin. Eleanor Cave’s rich (and beautifully illustrated) PhD thesis on his father Joseph Hooker’s botanical work in Van Diemen’s Land shows just how important convicts were to the history of botanical collecting. Indeed, local officials like Ronald Gunn worked closely with convicts in their liaisons with the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. A convict taxidermist, James Lee, was even employed locally to stuff birds; and renowned convict artist William Buelow Gould produced numerous illustrations of plants, birds and animals. (Gould’s Sketchbook of Fishes inspired the wonderful novel Gould’s Book of Fish, by Tasmanian author Richard Flanagan.) It is clear that Van Diemen’s Land was far from exceptional, and that in penal colonies all over the world convicts were used not just in botanical collecting, bird stuffing and painting, but as guides, porters, scouts and assistants. As Cave shows in her PhD, the recognition of the role convicts played centres them in natural history, and it also forces historians to take seriously the importance of the so-called periphery – both imperial/ geographical and social – in understanding empire, science and knowledge formation and circulation. Indeed, I have found evidence that transportation convicts were used in exploration and other kinds of expeditions in many locations, including Mauritius, the Cape Colony (where convicts were loaned out from Robben Island), and Mazaruni in British Guiana (where there was an isolated up-river penal settlement for locally convicted prisoners.)

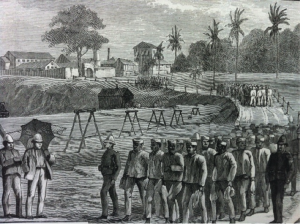

Convicts going to bathe, Mazaruni, Illustrated London News, 1888.

Nowhere was more peripheral and yet central to empire than the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. The Andamans were the largest penal colony in British India; and they were used for the transportation of tens of thousands of convicts from India and Burma during the period 1858 to 1945. They were also a place of apparent natural riches; not only because their Indigenous inhabitants were thought to have the capacity to unlock the mysteries of the origins of humankind, but also because of their beautiful flora and fauna. Joining Indigenous ethnographers were bird watchers, egg collectors, butterfly catchers, orchid admirers and geologists – all of who made a beeline for the Andamans in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The colonizing mission of 1857/8 included Burmese convicts, who accompanied British officers as servants and bearers.

After settlement, one early British resident, chaplain of the Islands Thomas Warneford, made a remarkable collection of shells during the 1870s. His extensive collection was acquired with assistance of his young children, as well as his convict servants. After his daughter was sent to England for schooling, her father wrote to her repeatedly about his collection, reminding her that she had not yet helped in cataloguing it, and in once instance enclosing a ‘pearly nautilus’ collected from Aberdeen beach and gifted to her by one of the family’s convict servants, a man he called James.

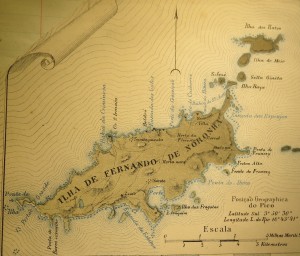

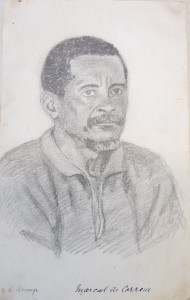

Certainly, the local knowledge possessed by convicts could be of enormous advantage to explorers, botanists and scientists. We find an excellent example of this in Fernando de Noronha, a small island 500km from the north-east shore of Brazil in the southern Atlantic Ocean, which was used as a penal colony during the nineteenth century. In the 1880s the first ever British scientific party was granted permission to land there. At its head was Henry Ridley, who was then director of gardens and forests in the Straits Settlements (Singapore, Penang and Malacca – themselves former penal settlements of the Indian Empire.) Ridley was travelling on behalf of the botanical and zoological departments of the Natural History Museum, which at the time was engaged in an expansive programme of specimen collecting. Ridley and his two compatriots spent four weeks gathering what they hoped was a complete collection of its flora and fauna. The naturalists arrived at an interesting time, for the new superintendent had recently implemented what was known at the time as the Crofton, or Irish, system of punishment, underpinned by the classification of prisoners, night time separation and daily associated labour. Though this is revealing of a different circuit of globalised penal practice, what I am fascinated by here is the allocation of a convict servant, Marçal Correia, to the party. Ridley later wrote that he had shown them how to collect fish in a rock-pool, using the roots of Tephrosia cinerea. He pounded them up with a club, and then stirred them into a coral rock pool. The fish became stupefied, and died, enabling the collectors to scoop them into their nets.

Fernando de Noronha, 1887. Reproduced by kind permission of the Archives of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

George Ramage, Sketch of convict Marçal Correia, 1887. Reproduced by kind permission of the Archives of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

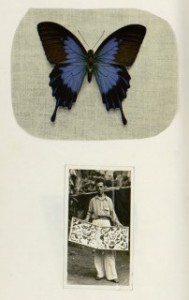

Elsewhere in Latin America, convicts were used as butterfly collectors. Up to the Second World War, French Guiana was a notorious penal colony where convicts sentenced to more than eight years’ transportation were forced to stay for the rest of their lives, as so-called libérés. With few opportunities for employment, one source of income was catching butterflies for sale on the international market. This kind of collecting was not strictly scientific, but fed into the developing commerce for such specimens. This will be no surprise for readers familiar with Henri Charriere’s epic book Papillon [Butterfly], a fictional account based on the author’s experiences as a convict (later made into a film starring Steve Macqueen and Dustin Hoffman). A key intermediary in butterfly collecting in Cayenne was Eugène Le Moult, who had one time had the fourth largest collection in the world. He sold up to 20 million specimens to clients including the Emperor of Japan.

Butterfly collecting in Cayenne, early C20th.

I still have much work to do in piecing together fragments from the archives and thinking through the significance of the role that both penal colonization and transportation convicts played in the history of science, collecting and knowledge production. There is the role of Indigenous people to consider too, in particular how those living on the borders of penal sites transmitted their knowledge of locality, flora and fauna to settlers – whether convict or free. An integrated approach to the history of people, place and environment promises rich dividends.

This blog is based on material found in archives in the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew; The National Archives, Kew; the British Library; and, the University of Cambridge. It also draws on nineteenth and twentieth-century printed articles and books. The Tasmanian material is from Eleanor Catherine Cave’s wonderful doctoral thesis, Flora Tasmaniae: Tasmanian Naturalists and Imperial Botany, 1829-1960 (PhD thesis, University of Tasmania, 2012). Thanks to Héloïse Finch-Boyer at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, for alerting me to the Cape Colony material. Readers might be interested in reading Charles Darwin’s papers online, or viewing William Gould’s Sketchbook of Fishes.

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Subscribe to Clare Anderson's posts

Recent Comments