Several days ago, I broke from reading through the notes of nineteenth-century Russian penal inspectors to admire the 23rd edition of the International Prison News Digest, a publication of the Institute for Criminal Policy Research. As I perused this amazing compendium, I was struck anew by the way in which certain facets of the prison experience seem to survive on through the decades, as if impervious to temporal and political alterations, thus shading in the somber tones of past centuries the experiences of today’s prisoners. Notwithstanding the admirable advances occurring within many carceral spaces, such as the use of drones and mini helicopters in Ohio prisons for surveillance purposes[1] and the scheduled abolition of “night soil buckets” in Ugandan prisons,[2] solutions to the challenge of prison overcrowding seem as elusive now as they have in times past.

The world’s largest prison

Kresty 2, located outside St. Petersburg

Recent developments in Russia echo this theme. The International Prison News Digest mentioned the current, ongoing construction of the world’s largest prison, the Kresty 2, which is arising in Kolpino, a suburb located twenty miles outside of St. Petersburg. This new prison, which features cross-shaped cellblocks in order to maximize prisoner surveillance, is being constructed at a cost of $378 million. It will open its doors early in 2016 to 4,000 prisoners who are now serving sentences in other locations, making it the largest penal structure in the world. Many of the components of traditional planned communities—sports facilities, workshops, religious areas, a hospital, a hotel for visitors,[3] a “fighting room,” a concert hall, a museum,[4] saunas, and a shooting range for the prison guards—have been incorporated into the overall plan.

The original Kresty prison, located on the banks of the Neva River in St. Petersburg, is to be transformed into an art gallery

The original Kresty

Yet, if current trends prevail, even a penal structure of such grandeur might not go far toward alleviating the severely overcrowded conditions within St. Petersburg area prisons. The namesake of Kresty 2, the original Kresty prison of St. Petersburg (referred to here as Kresty 1), has in recent years housed more than 12,000 convicts, over ten times the number it was intended to hold at the time of its adoption as a prison in the nineteenth century. The structure itself had originally been a warehouse for wine in the 1730s. After the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, when landowners ceased to be responsible for the imprisonment of their serfs, the imperial government opted to repurpose the building as a prison formally known as the St. Petersburg Prison for Solitary Confinement. As the prisoner population grew, the structure was slightly expanded. Between 1894 and 1900, A.O. Tomishko, a Russian State Prison Association architect, cleverly redesigned and augmented its floor plan. Prisoners on site were then used to build the cruciform, five-storied buildings that would later serve as the boundaries of their own confinement.[5]

A bird’s eye view of Kresty in St. Petersburg

Despite this renovation, and according to numerous archival records, Kresty 1, along with other local jails, exceeded its maximum prisoner capacity almost immediately upon its completion. Sanitation systems deteriorated and maladies such as tuberculosis and pneumonia flourished. Suicide was not uncommon. One penal inspector wrote that in such uncleanliness and congestion “even the most healthy man will surely die if he be kept there for three or four weeks.”[6] Another claimed that it would need to be completely reconstructed before being “rendered habitable, notwithstanding the fabulous sums of money it has cost.”[7] Notwithstanding reports of Western-style progress that were frequently issued to the international community, nineteenth-century Russian penal inspectors frequently—and accurately—described their nation’s prisons as dilapidated, filthy and overcrowded in internal documents. “The number of prisoners in each [cell] was very often twice and thrice in excess of the maximum allowed,”[8] wrote prison surveyor P. Kropotkin in his In Russian and French Prisons of nearly every prison he visited. As would other analysts, Kropotkin concluded that partially as a result of gross overuse, Russia’s penal structures were nearly “uninhabitable . . . beyond the scope of any theory of reform that stopped short of reconstruction.”[9]

One hundred and thirty years later, Kresty 1 is more overcrowded than it was during the darkest of imperial decades. During the 1990s, when it was home to over 12,500 prisoners, it was cited numerous times for human rights violations, including unsanitary conditions, violence and administrative corruption.[10] Twenty prisoners often lived in cells originally designed for solitary confinement.[11] In 1999, Vivien Stern used Kresty 1 as an illustration of the way in which tuberculosis flourishes within the filth that overcrowded prison populations produce. She pointed out that high prisoner counts have necessitated bed rotation: inmates sleep according to assigned shifts on unclean, triple-stacked bunks.[12] In 2004, over 5,000 prisoners in the St. Petersburg region organized a hunger strike in protest of administrative corruption and poor living conditions, both of which had increased as a result of prison overcrowding.[13]

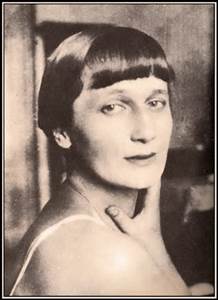

Anna Akmatova

During both imperial and Soviet eras, the Kresty was used to confine political prisoners and for the solitary confinement of dangerous elements. Anti-tsarist dissidents such as Leon Trotsky, A. Kerensky (future head of the Provisional Government) and A. Lunacharsky (the first Soviet People’s Commissar of Enlightenment) were imprisoned within it before 1917; after the Revolution, officials of the fallen imperial government as well as members of the intelligentsia and artistic communities had their turn. Anna Akmatova’s poetic work, “Requiem,” was conceived during her seventeen months of standing outside the Kresty prison walls in an effort to furnish provisions to her imprisoned son, Lev Gumilev. To another woman similarly waiting with her who asked her, “could anyone ever describe this?” Akhmatova answered, “I can.” She later captured the melancholy of the experience in verse.“During those days,” a few lines of the ten-part work reads, “only the dead smiled, glad to be at peace, and Leningrad, unneeded, swayed, throwing wide its penitentiary doors.” Since those days, during both the Soviet and post-Soviet eras, Kresty I has continued to house criminals, dissidents, and those awaiting trial.

Larger Prisons, larger prison populations

Though the concept of it astounds, it is possible that the soon-to-be largest prison in the world, Kresty 2, will go no further toward ameliorating St. Petersburg’s prison overcrowding issues than did Tomishko’s renovations of the 1890s. For, as Lord Woolf has pointed out his brilliant forward to “A Presumption Against Imprisonment,” current analyses indicate that the notable increases in the size of the prison populations that have offering over the last decade have not “achieved an improvement in protection to the public” nor have they had the net deterrent effect of ultimately reducing the use of imprisonment.[14] Yet, overcrowding is clearly “a cancer” that impedes prison reform by virtue of its sheer size and cost, among other reasons.

The Kresty, of course, is but one representation of an issue that is multinational in scope. According to the International Prison News Digest, Norway has contracted to rent prison space from the Netherlands in order to house its excess prisoners; the Netherlands has already been leasing penal space to Belgium for several years.[15] Reports furnished by Nepal’s Department of Prison Management indicate that its prisons are struggling to operate far above capacity.[16] The severity of conditions within India’s overfilled jails caused the nation’s Supreme Court to recently mandate that all prisoners who have served half their maximum term without trial (nearly two-thirds of incarcerated Indian prisoners) be freed.[17] The total prison population in the U.K. rose to 84,000 in 2013; in 1992 it stood at 45,000.[18] Indeed, few nations seem exempt from concerns relating to rising prisoner populations and the associated costs. However, at Lord Woolf notes, conviction rates will likely not be reduced by the building of massive, planned prisoner communities, such as Kresty 2. Concert halls, saunas and sports arenas for prisoners notwithstanding, the current conditions within prisons worldwide might well demand a fresh reconceptualization of the methods by which we seek to penalize and rehabilitate offenders.

References

[1] 23rd International Prison News Digest, digital edition, pg. 12. Institute for Criminal Policy Research.

[2] Ibid, p. 6

[3] Starodubtseva, Marina. November 5, 2014. “St. Petersburg Suburb will have Europe’s largest prison.” The Russia and India Report.

[4] Stewart, Will, and Damien Gayle. 20 October 2014. “Russia prepares to open Europe’s biggest prison with 4,000 inmates, a sauna and even a museum.” Mail Online.

[5] “Kresty Prison: A Forgotten Site of Memory?” October 3, 2010. William and Mary in St. Petersburg.

[6] M. Nikitin, qtd. in P. Kropotkin. http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/kropotkin/fortress.html

[7] Commission under Secretary of State Groth, qtd. in P. Kropotkin

[8] Kropotkin, P. In Russian and French Prisons. London: Ward and Downey, 1887. p 42

[9] Ibid p. 42

[10] “Kresty Prison.”

[11] August 7, 2012. “Russia’s Most Notorious Prison to Become Art Center.” Russian Times. http://rt.com/art-and-culture/prison-become-art-center-055/

[12] Stern, Vivien. Prison Reform and Public Health: the case of tuberculosis in the former Soviet Union.” The European Journal of Public Health.

http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/content/eurpub/10/1/4.full.pdf

[13] Titova, Irina. February 7, 2004. “Mass Hanger Strike in City Prisons Ends After Talks.” The St. Petersburg Times. http://sptimes.ru/index.php?action_id=2&story_id=12377

[14] The British Academy. “A Presumption Against Imprisonment.” Prison Disturbances, April 1990. P. 10

[15] 23rd International Prison News Digest, p. 1

[16]Ibid, p. 2.

[17] Ibid, p. 3

[18] “Presumption,” p. 16

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

Subscribe to Carrie Crockett's posts

Really appreciate you sharing this blog post.Much thanks again. Awesome.

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read anything like this prior to. So nice to uncover somebody with many original thoughts on this subject. realy appreciate beginning this up. this fabulous website are some things that is required on the web, an individual with some originality. valuable work for bringing something new for the net!