Engraved portrait of John Evelyn by Nanteuil, for which Evelyn sat on 13 June 1650, while visiting Paris. From the Fairclough Collection, EP36, Box 2, p. 245.

On 13 September 1666, only a few days after the Great Fire of London had finally been quenched, John Evelyn presented Charles II with a survey of the ruins, ‘for it was now no longer a Citty’*, and a design for the new London, drafted with extraordinary speed – but then Evelyn had long been reflecting on how London could be improved and made more like Rome, which he had visited and much admired. His plan ‘combined the practical with the visionary in a rather exceptional way’+, incorporating piazzas and plenty of open spaces, wide streets and a river-front development and stressing the importance of using good quality paving and brick or stone, as opposed to wood.

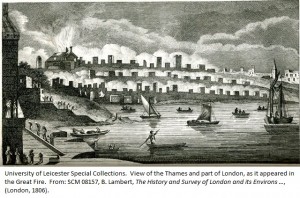

Evelyn gives us a vivid and dramatic account of the Fire, which started at about 10 pm on 2 September. The flames took hold during the night, ‘if I may call that night which was light as day for 10 miles round about, after a dreadfull manner’, consuming the tall wooden houses clustered in narrow and dirty lanes, tinder-dry from a long hot spell. People were so astonished by the violence of the fire, Evelyn observed, that they ‘hardly stirr’d to quench it, so that there was nothing heard or seene but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures …’** The Thames was alive with barges and boats, laden with whatever goods people could save.

View of the Thames and part of London, as it appeared in the Great Fire. From: SCM 08157, B. Lambert, The History and Survey of London and its Environs …, (London, 1806).

‘All the skie was of a fiery aspect, like the top of a burning oven, and the light seene above 40 miles round about for many nights. God grant mine eyes may never behold the like, who now saw above 10,000 houses all in one flame; the noise and cracking and thunder of the impetuous flames, ye shrieking of women and children … the aire all about so hot and inflam’d that at the last one was not able to approach it, so that they were forc’d to stand still and let ye flames burn on …’

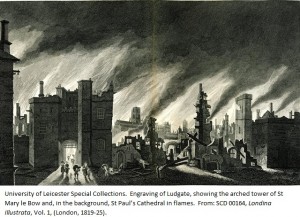

Engraving of Ludgate, showing the arched tower of St Mary le Bow and, in the background, St Paul’s Cathedral in flames. From: SCD 00164, Londina Illustrata, Vol. 1, (London, 1819-25).

By the next day, Tuesday September 4th, the fire had spread over most of the City, destroying St Paul’s Cathedral and threatening the Court at Whitehall. ‘The stones of Paules flew like granados,’ writes Evelyn, ‘ye mealting lead running downe the streets in a streame, and the very pavements glowing with fiery rednesse’.++ After previous half-hearted attempts to create firebreaks, using gunpowder to blow up undamaged houses, the authorities finally decided on the Wednesday that as much property as necessary must be sacrificed and the resulting wider gaps, added to the fact that the strong east wind died down, enabled them to take control of the situation.

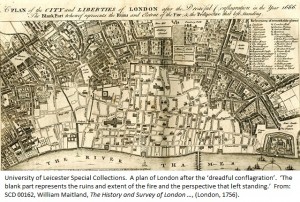

A plan of London after the ‘dreadful conflagration’. ‘The blank part represents the ruins and extent of the fire and the perspective that left standing.’ From: SCD 00162, William Maitland, The History and Survey of London …, (London, 1756).

Not surprisingly, Evelyn’s plans for a new London, like those of Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke, came to nothing – after such devastation, rebuilding had to take place as speedily as possible and stirring up a swarm of legal actions over property rights was out of the question.

Evelyn’s diary is a fascinating record of the turbulent times and momentous events, which he witnessed in the course of his 86 years – the Civil Wars, the Restoration and the Plague of 1665, in addition to the Great Fire. Our current exhibition, celebrating the man and his achievements, can be seen in the basement of the Library. Much of the material on display comes from the Fairclough Collection of 17th century engraved portraits, photographs, books and pamphlets. The exhibition runs until 29 January 2016. Entry to the library is free but controlled, so if you are not a student or member of University staff, please ask to be let through the barrier. Details of staffed opening hours are available on the library website.

John Evelyn, Memoirs Illustrative of the Life and Writings of John Evelyn Esq. …, Vol. 1, (London, 1819), *p. 397, **pp. 391-2, ++pp. 392-3, SCT 00078

+Florence Higham, John Evelyn Esquire, (London, 1968), p. 61, FAIR B/EVE/HIG

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Recent Comments