In a follow-up to his previous blog post, The Beast in Me, Museum Studies PhD student Armand De Filippo reports on the most recent adventures of our “Ethiopic Manuscript”, MS 210. Armand’s latest article reflects on the experience of conducting cutting-edge digital imaging work with the manuscript at the British Library, in collaboration with Mnemoscene and Cyreal.

In a poignant episode of the critically acclaimed BBC tv series, ‘Detectorists’, detectorist Lance (played by Toby Jones), visits the British Museum to gaze upon the Anglo-Saxon jewel he had earlier unearthed with the help of his metal detector.[1] This find represented the pinnacle of his lifelong hobby as a detectorist and was the focus of much emotional energy. However, rather than being thrilled to see the object displayed with all the other culturally and historically important artefacts in the gallery of a national museum, Toby was saddened and perturbed. In conversation with a curator at the museum he expressed a sense of guilt at having had a part to play in confining the object to a glass case. Lance’s precious artefact seemed bereft – “like an animal that’s been trapped in a cage”. It was, in his view, no longer free and in the world but had become ossified on display. To Lance’s further dismay, the artefact had not even been given a name, just a catalogue number. The curator, in an attempt to reassure the detectorist, offered an alternative perspective. Rather than thinking of it as ‘frozen’ as part of a museum collection and at the end of its life, he said, he might think instead of this as simply another chapter in the object’s life story. Within the University’s Special Collections is a manuscript that enables us to consider a similar biographical trajectory. MS210, an object we explored a little in an earlier blog, ‘The beast in me’ (June 2018) was accessioned in the early part of the twentieth century, and it has been in a box, sitting on a shelf in the basement ever since, only very occasionally being retrieved for inspection or study. And like Lance’s medieval aestel, it is not known by a name only a catalogue number.

‘It looks quote lonely by itself’, said one research participant on encountering MS210 in a display case. ‘I’m used to the idea that they are together in libraries.’ They continued, ‘I expect that in Leicester it is being kept in a dark, closed archive and it doesn’t sit with the other books and its friends.’ If this sense of isolation, not to mention sadness, is cause for concern, as these words spoken by a participant in my PhD research project suggest, then some solace and comfort may lie in the knowledge that this manuscript has recently been at the centre of a network of human and on-human entanglements. As if to underline the comments made by the museum curator in the ‘Detectorists’ that being accessioned into a collection is not the end of an object’s active collaboration and engagement in the world of people and things, MS210 has been metaphorically thawed as the focus, quite literally, of a number of digital techniques at the forefront of imaging technology.

Inspired by my research with MS210 in Special Collections[2] I began to reflect further on the notions of materiality which inhere in the digital manuscript – from the physical detail which is denied to the human eye but can be revealed by digital technology, to the finger prints all over the screen of an iPad evidencing the tactile interaction between person and digital object. At the same time, intrigued and encouraged by the gasps of awe and surprise elicited by research participants on discovering material details when interrogating the digital manuscript, I began to consider the transformative potential of encounters with the MS210 rendered in 3-D as a textured, interactive landscape. Paradoxical though it may seem, could digital technology help us build connections with past lives and eras by creating a sense of empathy and affinity with past readers of the manuscript? Many of the digital technologies that reveal and expose the physical qualities of manuscripts tend to be employed ‘behind the scenes’ for scholarly investigations and conservation work, but what if these were also used to enhance corporeal and sensory encounters between audiences and manuscripts?

Typically presented as a two-dimensional surface with its folios opened to show a double page spread in vitrine when on display, this belies the material complexity of a manuscript. MS210 is a cube-like object made more labyrinthine by its inherent dynamic capacity to open out into multiple surfaces which are at once hidden and revealed as its folios are turned. The challenge and possibilities represented by digitally capturing MS210 in 3-D intrigued digital heritage imaging specialists, Mnemoscene, Cyreal and RTI (Reflectance Transformation Imaging) expert, Xavier Aure. With the support of the British Library’s Digitisation Services, who hosted a fascinating and creative day of investigation, we took some important steps to develop a ‘proof of concept’, which, we hope, will signal the start of a longer-term research and development project. Without the interest, support and generosity of these people and organizations this innovative and exciting pathfinding project would not be underway.

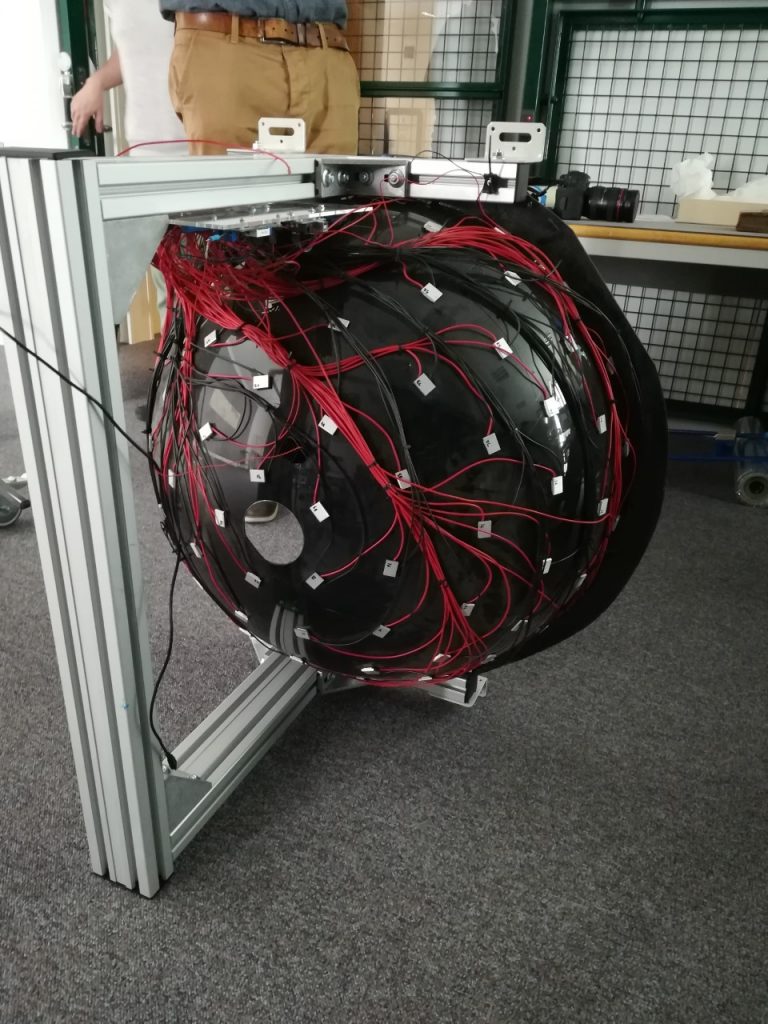

Something from the set of Dr Who? Not quite, but, nonetheless, it has a part to play in blurring the boundaries between past, present and future

If this dark, LED sparkled dome is reminiscent of a starry constellation, it is entirely appropriate. Walter Benjamin uses the idea of a constellation to rethink the conventional linear notion of time. Revising the causal connections of traditional historicism, Benjamin suggests that the ‘starry lights’ of past events ‘are emitted at different times even if they are perceived together’. This implies a more cosmic than chronologically categorized idea of history. A ‘meanwhile’ which enables other voices to be heard, and provides alternative narrative spaces, metaphorical and phantasmic.[3] It is an approach that enables us time and space to consider those human and non-human collaborators in the making and life story of MS210: the craftspeople, readers, animals, insects, minerals and plants that are often hidden beneath layers of historical and contextual interpretation.

Not unlike the digital today, a medieval manuscript represented the cutting edge of communication technology of its era. And like the digital, manuscripts were not the solely visual phenomena they are often portrayed as when they are silently displayed behind glass in exhibitions. Both modern digital technologies and ancient manuscripts can incorporate verbal and aural signifiers. In an attempt to both evoke a past in which perhaps inscribed speech was enacted upon listeners and to add an auditory layer of interpretation to ensure that MS210 was apprehendable to visual impaired audiences, an audio-described MS210 is being included in this project.[4] In collaboration with VocalEyes, sonic textures will be added to ocular ‘page-scapes’. Further tactile features might also be manufactured from the digital renderings of the folios of MS210, allowing us to take a step further to creating a space of encounter as a sensory nexus and one full of happening. Thus, rupturing the idea of the manuscript and its display space as silent and uninhabited.

Returning to Benjamin’s notion of a constellation, we find another or additional, way to think about this notion. When we look up at the stars some are in focus while others are obscured. Take a different bodily stance, squint your eyes, tilt your head and, suddenly, other stars begin to shine, while those first glimpsed fade into the darkness. Of course, there is an intriguing analogy here with how, in the rhythm of folding over its folios, a manuscript simultaneously conceals as it reveals. In turning over a page we expose a surface while, at the same time, hiding a surface. One is dependent upon the other. But both looking at the stars, and, or, turning the pages of a book also provide us with a trope for the biographical journey of MS210. At times and in certain places, the manuscript shone at the centre of events. For example, the manuscript’s possible involvement in the actions which ensued following the Battle of Magdala in 1868.[5] It’s starry glimmer perhaps dimmed a little when entered the University’s collections. Yet, now it sparkles again as the principal protagonist in an innovative collaborative digital research project. Just like the fictitious British Museum curator in ‘Detectorists’ posited, the entry of an object into a collection does not mark the end of its life story, it is simply another episode in its ongoing entanglement with a vast network of human and non-human lives and across a timescale which transcends human lifetimes and historical categories. MS210 is a temporally complex object which exists in contemporary relation to those who apprehend it – in the past, now and in the future. If the relationship between a centuries’ old manuscript and the latest digital technology elicits a sense of anachronism, perhaps we should think again – or differently about anachronisms. Anachronism need not be employed pejoratively, and can provide us with a shaper tool with which to probe our relationship with the past. Film maker, Derek Jarman, for instance, as Robert Mills points out, used sonic and visual anachronisms ‘artfully and knowingly’ to challenge the ‘heritisation and museumisation of that entity we call the past.’[6] MS210 is not simply stuck in the time of its creation, but is an affective presence in the present. As evidenced perhaps, in the way in which a number of people are working alongside and with it. MS210 jolts us out of our historical comfort zones, forcing us to reflect ‘on the past as a living present’ and defying the constraints of conventional chronological frameworks.[7] Evoking Benjamin’s constellation, encountering MS210 provokes us to consider the present as heterogenous – a complex mix of ‘memories and matter which flicker into view, fade, only to reappear brighter and more potent than before. It also incites a nagging doubt…Just as detectorist Lance was unhappy that the Anglo-Saxon aestel he discovered was not given a name by the museum, simply a number (catalogue number: R5010ST78), so, I cannot help but wonder if Leicester’s Ethiopic manuscript deserves more than the alphanumeric appellation, ‘MS210’. As a participant in my PhD research project observed, ‘it’s got a life history, so, it must have some kind of feelings’.

With thanks to the following project partners

www.bl.uk/digitisation-services

References

[1] ‘Detectorists’ BBC TV Christmas Special, 23/12/15

[2] See previous blog entry, ‘The Beast in Me’ (08 June 2018)

[3] See Carolyn Dinshaw, Getting Medieval, (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1999), (p.18)

[4] The prosopopoeic ‘Riddle 26’ from the 10th century Exeter Book which gives a manuscript, its materials and its non-human collaborators voice is mentioned in an earlier blog, ‘The Beast in Me’.

[5] See earlier blog, ‘The Beast in Me’.

[6] Robert Mills, Medieval Modern, (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2018), (p.177)

[7] Ibid., (p.177)

Subscribe to Simon Dixon's posts

Subscribe to Simon Dixon's posts

Recent Comments