1. Immersive experience installed in the David Wilson Library, May 2018, as part of PhD research undertaken by Armand De Filippo.

MS210 is a manuscript held in the Special Collections of the David Wilson Library, University of Leicester. This manuscript is the focus object of a PhD research study being undertaken by Armand De Filippo at the School of Museum Studies and funded by a CSSAH scholarship.

Manuscripts are an enduringly popular feature of exhibitions, yet, they are always contained in vitrine and often we cannot see them well, let alone touch them. This research project explores what happens when we do get to engage with manuscript materials using multiple senses and asks whether this has any potential implications for how museums and libraries exhibit manuscripts in the future. With heightened attention to the manuscript’s materiality and by utilizing the potential of multimedia to enable physical and sensory encounters with manuscript materials, this study seeks to discover if more potent emotional and imaginative visitor reactions can be inspired.

A life-thief stole my world strength,

Ripped off flesh and left me skin,

Dipped me in water and drew me out,

Stretched me bare in the tight sun;

The hard blade, clean steel, cut,

Scraped – fingers folded, shaped me.

Now the wind-stiff joy

Darts often to the horn’s dark rim,

Sucks wood stain, steps back again –

With a quick scratch of power, tracks

Black on my body, points trails.

Shield-boards clothe me and stretched hide,

A skin laced with gold.

Audio Player

Text from the Exeter Book reproduced in Scraped, Stroked and Bound, ed. Jonathan Wilcox (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013), pp.viii-ix. Read and translated by Dr Chris Monk.

This extract, although from a collection of Anglo-Saxon poems and riddles, written in the 10th century, could just as well apply to a much later manuscript, one replete with its own set of mysteries and uncertainties, held in the University of Leicester’s Special Collections. The manuscript enigmatically known as ‘MS210’, has been with the University since shortly after it was founded. Bequeathed to the University College in the 1920s, it has rested in its case, quietly guarding the details of its life and experiences. Indeed, it is with its slipcase, that the mystery begins.

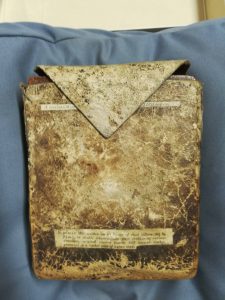

- 2. MS 210, Ethiopic manuscript, leather slipcase with typed labels

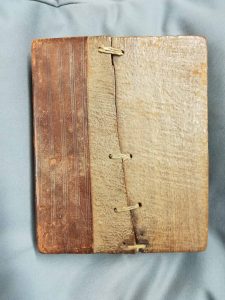

- 3. MS 210, Ethiopic manuscript, front cover. The book board is only partially covered in tanned leather and has been repaired. The nature of the repair suggests it may have been made ‘on the fly’.

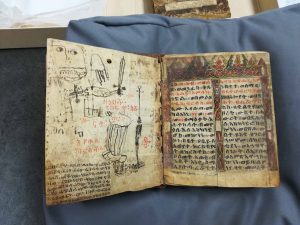

- 4. MS 210, Ethiopic manuscript. The first folio contains some drawings and what appears to be a talismanic verse seeking protection from harmful forces. This may have been added by the manuscript’s owner.

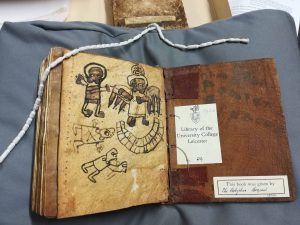

- 5. MS 210, Ethiopic manuscript. The blank final page seems to have been used by the owner of the manuscript to record his or her own illustrated interpretation.

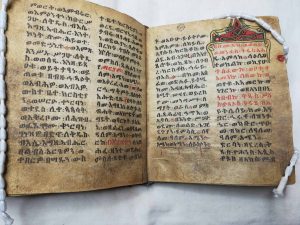

- 6. MS 210, Ethiopic manuscript. A decorated border and rubrics helped the reader to navigate the book, marking the start of a new section of text. (Red ink was often used for this purpose).

Two typed and cut labels ascertain that the manuscript inside is Armenian and dates from the 14th century. Yet, all we need do is read the Library’s catalogue entry for the manuscript to see that it is described as an 18th century Ethiopic manuscript written in Ge’ez, primarily relating the story of ‘the martyrdom of St Cyriacus and his mother St Julitta’. So, which are we to believe? Perhaps, quite simply the manuscript was wrongly identified at some time in the past and the identifying label on the slipcase has remained stubbornly attached. Or, even though they fit like hand-in glove, may be the slipcase was never made for MS210, but for a different manuscript altogether?

On this, the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Magdala, MS210 poses another question? If it is Ethiopian, how did it get to Leicester and why? Lending weight to the notion that the biographies of persons and things are inextricably interwoven the documentation accompanying MS210 suggests that the manuscript was taken as a memento ‘from an Abyssinian chief’ by a war correspondent following the British military campaign in 1868. Seemingly, the manuscript was then bought in London some years later and then ended up in the hands of a local Leicester book seller, Caleb Robjohns, from whence it found its way, as part of a bequest, into the collections of the forerunner of what is today the University of Leicester. In light of the homiletic, hagiographic nature of the textual content, we might surmise that MS210 has been on a trajectory taking it from sacred object to commodity. However, today, it gets the attention of conservators, image scientists and curators who keep it in a carefully controlled environment, which suggests that, in a way, it is once more an object of veneration. But the story does not end there. At the end of the Battle of Magdala, according to contemporary reports, it took 15 elephants and 200 mules to carry away the loot captured by Anglo-Indian forces. The collections of a number of major British libraries and museums now hold objects acquired as a result of this military campaign in what is now Ethiopia, and they have long been the focus of attempts to repatriate them. We have no way of knowing how or why MS210 came to Leicester, or exactly where it came from, but if it was part of the ‘Magdala treasure’, that would add a new chapter to its life story and lend the object additional meaning, as a ‘contested object’.

So, why does a thousand-year-old Anglo-Saxon riddle pertain to MS210? Well, possibly for two reasons. Firstly, because the form of binding used to append MS210 is remarkably like that used to bind the earliest known intact European book, the 7th century St Cuthbert Gospel. This binding style, known as Coptic stitching or sewing, was a complex process requiring great skill and craft, but it resulted in the finished codex – the front board, each of the gatherings, and the backboard – being incredibly flexible – the ‘yoga laptop’ of its day. Not only does this imply that the physical structure of MS210 displays Anglo-Saxon heritage, but it also challenges us to rethink overly-clear distinctions between the philosophical, cultural and art traditions of ‘The West’ and elsewhere.

The second reason is that the opening riddle is prosopopoeic. Thus, in a sense, the manuscript directly addresses us, and asks us to identify it through its material characteristics. This is significant because it calls on us to look beyond the textual content of the manuscript, beyond the information text of labels and catalogue entries and to consider ‘the things themselves’. While we frequently engage with the world around us by interpreting and exchanging meanings, our tendency is to overlook, or, as is often the case within interpretive settings (museums, libraries, archives) where manuscripts are frequently displayed, we are denied opportunities for the perceptual, bodily and sensory experiences created by encounters with specific materials. If we focus exclusively on the socio-cultural, historical and political meanings with which objects are often overlaid, and at the expense of our corporeal relationship with the material things around us, we risk closing off other ways of knowing.

The Exeter Book riddle draws our attention to the physicality of the manuscript and evokes a visceral reaction to the paraphernalia of manuscript making, inks and bindings, as well as the parchment itself, with all its hair follicles, insect bites and rib-shaped folios, replete with the patina of age and human use. Odd though it may seem at first glance, it is access to these physical details that digital technology can enhance. View MS 210, which is now available via the Library’s Special Collections Online, and the potential of the digital to create a sense of ‘material proximity’ quickly becomes apparent. Not only does the digital version of the manuscript rupture our habit of considering the page of a manuscript to be two-dimensional, but it signposts potential gateways to ‘inaccessible pasts’.

By refocussing on the materiality of the manuscript and exploiting digital media to enable physical and sensory encounters with medieval manuscript materials, we can expand the potential for different ways of knowing. Knowing that is not exclusively intellectual but is enabled via our sensory modalities and though our imaginations and emotions.

- 7. Display case draw containing oak galls, inks and pigments used by medieval scribes and illuminators.

- 8. Beeswax, barley and maize were all used in the processes of creating a manuscript. A feather quill and reed pen were used to put ink on the parchment. An example of quarter sawn book board is also shown. This medieval technique used in European codex manufacture helped prevent the book boards splitting as has happened to the front cover of MS210 shown in image no.3 above.

- 9. Scrapers like this were used to remove hair and fat from the animal skin used to make parchment. The scents of Frankincense, Myrrh and Lubanja are sometimes retained within the folios of a manuscript and can still be smelt if we are lucky enough to get close enough.

- 10. A full-size piece of vellum (calf-skin) suspended on a frame and prepared ready for writing on. The pattern of the animal’s spine can still be seen running along the central length of the vellum.

Subscribe to Simon Dixon's posts

Subscribe to Simon Dixon's posts

Recent Comments