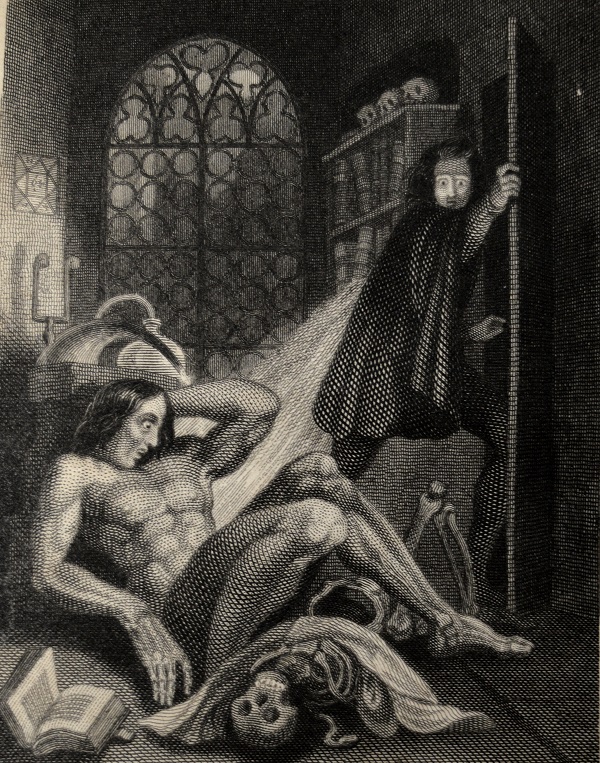

University of Leicester Special Collections. Frontispiece to the first illustrated edition of Frankenstein, drawn by Theodor von Holst and engraved by W. Chevalier. From: SCS 01395, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Frankenstein, (London, 1831).

In the fabulously Gothic frontispiece of the first illustrated edition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: or The Modern Prometheus, published in 1831, the monster, dramatically lit by the moon, lies in a medieval chamber, complete with grinning skeleton. The artist, Theodor von Holst, has chosen to show the moment, when Victor, overcome with horror at the being he has created, rushes from the room:

‘How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe, or how delineate the wretch whom with such infinite pains and care I had endeavoured to form? His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful! – Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of the muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness, but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with … his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips …’1

The novel had first been published anonymously in 1818, with a preface ostensibly by the author, but, in fact, written by her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley. This revised edition, which came to the University as part of the Robjohns Bequest, has an introduction by Mary, in which she gives an account of the circumstances leading to its conception and writing in summer 1816, when she and Percy visited Lake Geneva and were ‘neighbours of Lord Byron’:

‘It proved a wet, ungenial summer, and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house. Some volumes of ghost stories, translated from the German into French, fell into our hands … “We will each write a ghost story,” said Lord Byron; and his proposition was acceded to. There were four of us. The noble author began a tale, a fragment of which he printed at the end of his poem of Mazeppa. Shelley … commenced one founded on the experiences of his early life. Poor Polidori had some terrible idea about a skull-headed lady … I busied myself to think of a story, – a story to rival those which had excited us to this task. One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror …’2

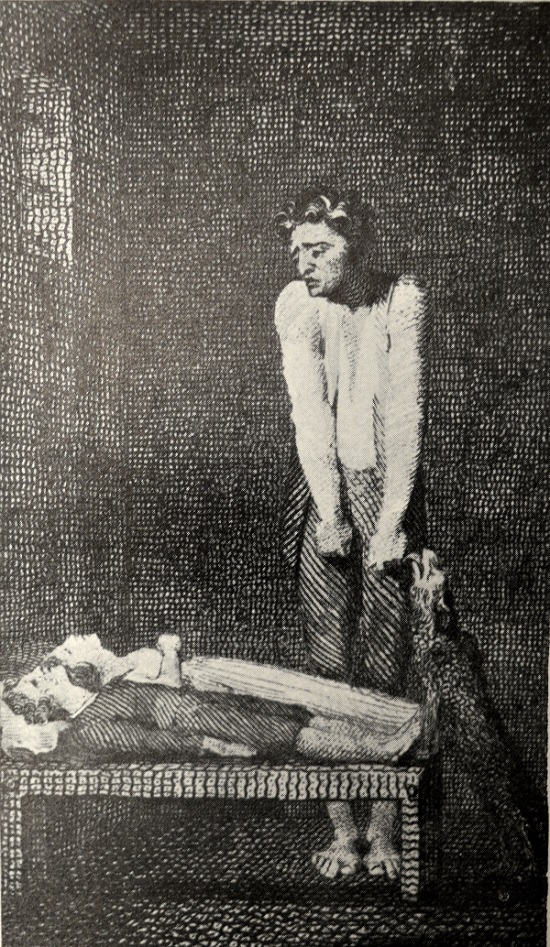

University of Leicester Special Collections. This illustration by William Blake from an early work by Mary Shelley’s mother, shows ‘crazy Robin’, a tragic figure, driven mad by his struggles to support his family and the deaths of his wife and children. Robin’s appearance uncannily foreshadows that of Frankenstein’s monster. From SCS 04763, Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories, (London, 1906).

Mary’s parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, were both authors and political philosophers. Her mother died only 11 days after her birth and she was brought up by her father, along with Fanny, Mary Wollstonecraft’s first, illegitimate daughter, Charles and Clara, the two illegitimate children of Mary Jane Clairmont, whom Godwin married in 1801, and a fifth brother William, born of this second marriage – so an unorthodox family of 5 siblings. In summer 1816, she was still only 18, with her 19th birthday coming up on 30 August, and Shelley (whom she had first met, when she was 14 and fallen in love with, when she was 16) was five years her senior. John William Polidori, Byron’s personal physician, was 21. Byron was the eldest of the four, at the grand old age of 28. There was also a fifth member of the party, not mentioned in Mary’s preface, Claire (Clara) Clairmont, who had begun an affair with Byron and was already pregnant by him.

University of Leicester Special Collections. ‘New Morality’, a famous caricature of 1798 by Gillray, attacks the new moral principles that emerged from the French Revolution. From the Cornucopia of Ignorance, various writings by the admirers of these revolutionary ideals fly out, among them The Wrongs of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft, mother of Mary Shelley, and Political Justice by William Godwin, her father (which is being read by a braying ass). From: SCM 12881, The Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine, (London, 1799).

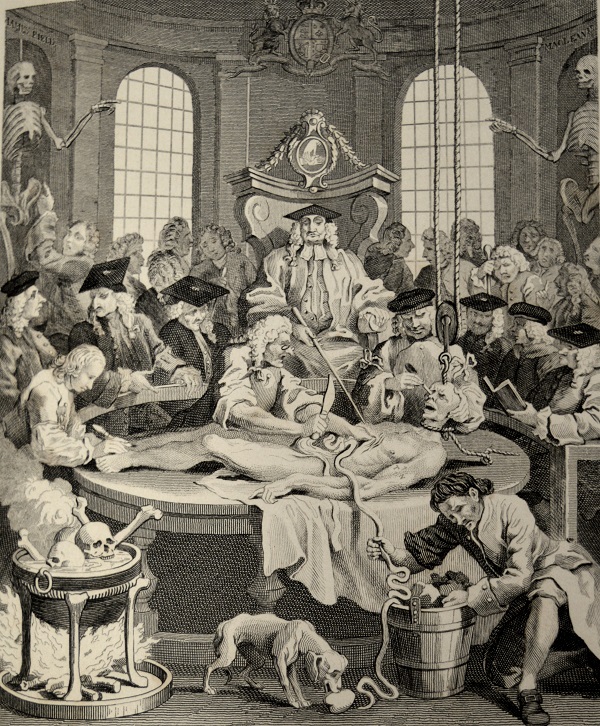

University of Leicester Special Collections. ‘The Reward of Cruelty’ from ‘The Four Stages of Cruelty’ by William Hogarth. Frankenstein was written during the era of bodysnatching and the Anatomy Act, regulating the practice of anatomy and the treatment of all bodies used for dissection, was passed in 1832, the year after the illustrated edition of the book discussed here was published. From: SCM 09547, William Hogarth, The Works of William Hogarth, (London, 1833).

Polidori, who went on to write The Vampyre, which first appeared in the New Monthly Magazine in 1819, gives a rather different version of the circumstances of the gestation of Frankenstein, revealing the tensions and undercurrents going on between the group. In particular, he describes an outburst by Percy:

‘June 18 … L.B. [Byron] repeated some verses of Coleridge’s Christabel, of the witch’s breast; when silence ensued, and Shelley, suddenly shrieking and putting his hands to his head, ran out of the room with a candle. Threw water in his face, and after gave him ether. He was looking at Mrs S [this refers to Mary, even though, at that stage she and Percy were not married – more of that later], and suddenly thought of a woman he had heard of who had eyes instead of nipples, which, taking hold of his mind, horrified him.’3

Polidori also makes it clear that, over that summer, he was regularly giving ether or laudanum to Shelley and Black Drop, which contained opium, to Byron – the mix of four such highly-strung personalities, the dramatic setting, the emotions – love, infatuation, jealousy and resentment – boiling beneath the surface and the hallucinations induced by opiates was an explosive one.

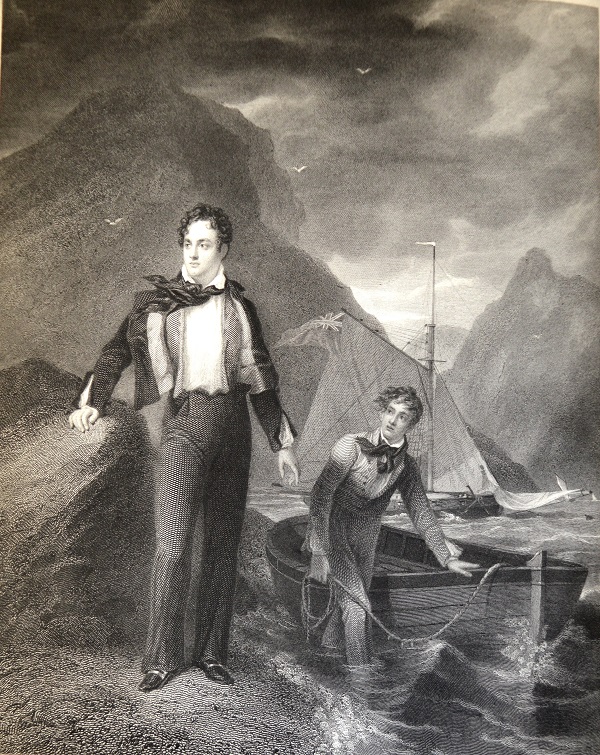

University of Leicester Special Collections. ‘Lord Byron at the age of 19’, engraved by W. Finden from a painting by G. Sanders. This portrait shows Byron, his hair and clothing ruffled by the wind, in a typically heroic and romantic pose, his unfortunate companion, meanwhile, standing up to his calves in the water. From: SCM 09397, Thomas Moore, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron …, Vol. I, (London, 1830).

Thomas Moore also gives us an account of events in Lake Geneva. When the group agreed to write something in imitation of German ghost-stories, Byron, according to Moore, told Mary, ‘You and I will publish ours together’. If this is so, it was a fantastic offer, made to someone, who had yet to prove herself as a writer. Byron ‘then began his tale of the Vampire; and, having the whole arranged in his head, repeated to them a sketch of the story … but … made but little progress in filling up his outline.’ From this sketch, Moore asserts, Polidori ‘vamped up his strange novel of the Vampire’.4 An 11-page ‘Fragment’ of Byron’s story was published with Mazeppa. The central figure, Augustus Darvell, suffers from a mysterious wasting disease:

‘It was evident that he was prey to some cureless disquiet; but whether it arose from ambition, love, remorse, grief, from one of all of these, or merely from a morbid temperament akin to disease, I could not discover …’5

Although Mary was becoming known as ‘Mrs Shelley’, in summer 1816 Percy was still married to Harriet Shelley, whom he had abandoned to elope with Mary. Later that year, on 9 November, heavily pregnant, Harriet drowned herself in the Serpentine. Her body was not found until 10 December and on only 30 December Percy and Mary were married.

Eight years on from the events that gave rise to Frankenstein, out of the group of friends – Mary, Percy, Polidori and Byron – only Mary was still alive. In debt and frustrated by his lack of success as a writer, Polidori took prussic acid in December 1821. Percy was drowned in a storm in the Gulf of Ischia on 8 July 1822. Byron famously died in Greece on 19 April 1824; he had pledged himself to fight for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire, but fell ill before the campaign commenced, succumbing to fever and, perhaps, sepsis. Claire Clairmont, however, outlived Mary (who died of a brain tumour in 1 February 1851), surviving into her 80th year.

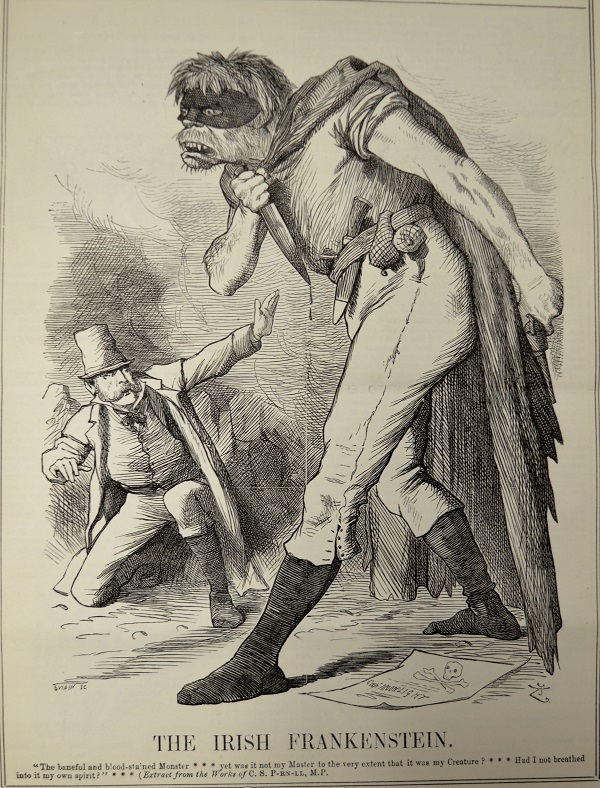

University of Leicester Special Collections. ‘The Irish Frankenstein’ by John Tenniel. One of several cartoons from Punch, inspired by Shelley’s monster, this is a comment on the Irish nationalism of Charles Stuart Parnell. The accompanying text parodies Mary’s words: ‘How can I delineate the Monster which with such infinite pains and care I had endeavoured to form? … I had turned loose into the world a depraved Horror, whose delight was in carnage and chaos: had it not murdered my countrymen …?’ From: PER 050 P9360, Punch, (London, 20 May 1882).

- Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Frankenstein, (London, 1831), p. 43, SCS 01395

- Ibid., pp. vii-ix

- Christopher Frayling, Nightmare: The Birth of Horror, ( London, 1996), p. 26

- Thomas Moore, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron : with Notices of his Life, Vol. II, (London, 1830), p. 31, SCM 09398

- John William Polidori, The Vampyre: 1819, (Oxford, 1990), introduction p. 2, 823.79 POL

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Recent Comments