350 years ago this month, during the early hours of Sunday 2 September 1666, the Great Fire of London, which had broken out in the Pudding Lane bakery of Thomas Farynor, began to spread with terrifying speed through the city’s crooked, narrow streets, lined with wooden buildings. One consequence of the Fire, irreparable damage to Old St Paul’s Cathedral, although it might have paled into insignificance beside the fate of the tens of thousands made homeless, nevertheless had a tremendous symbolic and emotional impact.

John Evelyn has left us a vivid eye-witness account from 4 September: ‘The stones of Paules flew like granados, ye mealting lead running downe the streets in a streame, and the very pavements glowing with fiery rednesse …’1

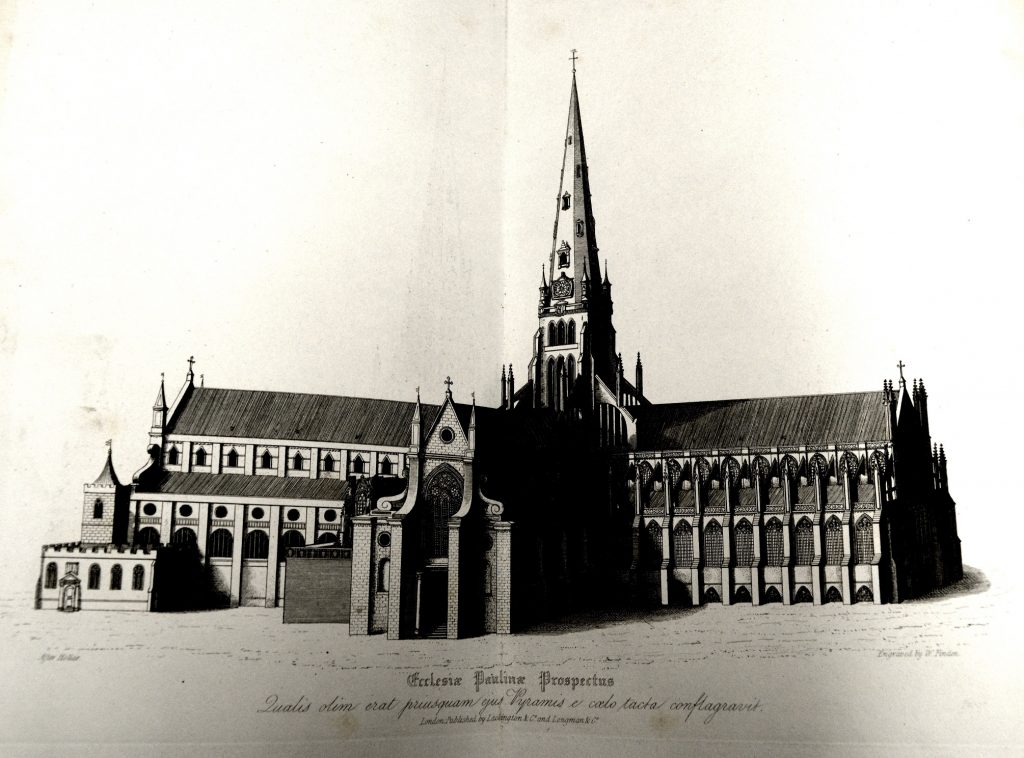

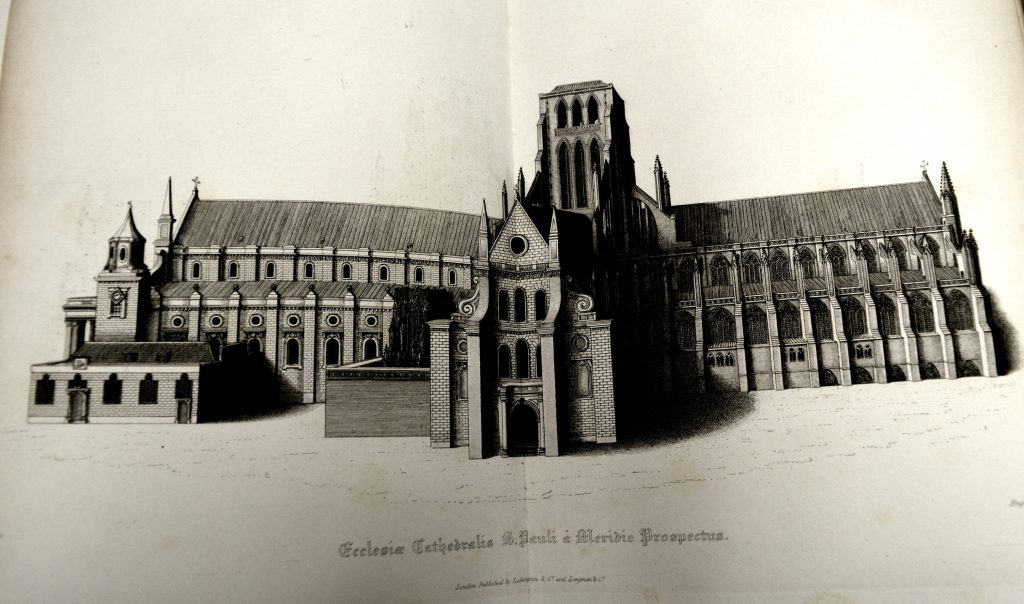

University of Leicester Special Collections. A view of Old St Paul’s, before the fire of 1561 from: SCT 00908, William Dugdale, The History of St. Pauls Cathedral in London : From its Foundation Untill these Times …, (London, 1818).

Ironically, the building of Old St Paul’s had begun after another fire in 1087, which completely destroyed an Anglo-Saxon church on the same site (in all probability, a wooden structure). Work on the Cathedral continued for over 200 years, temporarily interrupted by yet another fire in 1135. The building was enlarged over the years and by the mid-14th century had become ‘the finest in England in its time’3. It was a building to inspire awe, with its 489 feet high spire (a timber framework covered by lead) and magnificent nave, known as Paul’s Walk, which was 586 feet in length4.

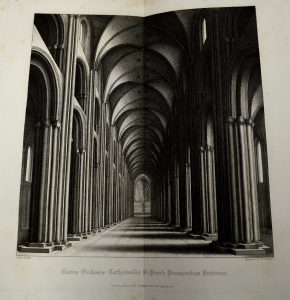

University of Leicester Special Collections. The nave, known as Paul’s Walk, from: SCT 00908, William Dugdale, The History of St. Pauls Cathedral in London : From its Foundation Untill these Times …, (London, 1818).

Paul’s Walk is shown in all its peaceful splendour in this engraving by W. Finden, after Wenceslaus Hollar. But by the 16th century it had become a hub for activities inappropriate to a place of worship, a meeting-place for exchanging gossip and transacting business. In 1628, John Earle penned this evocative description:

‘Paule’s Walke is the lande’s epitomy, or you may call it, the lesser Ile of Great Brittaine. It is more than this, the whole worlds map, which you may here discerne in its perfect motion, justling and turning. It is an heape of stones and men, with a vast confusion of languages, and were the steeple not sanctified, nothing liker Babel. The noyse in it is like that of bees, a strange humming or buzze- mixt of walking, tongues and feet. It is a kind of still roare, or loud whisper.5’

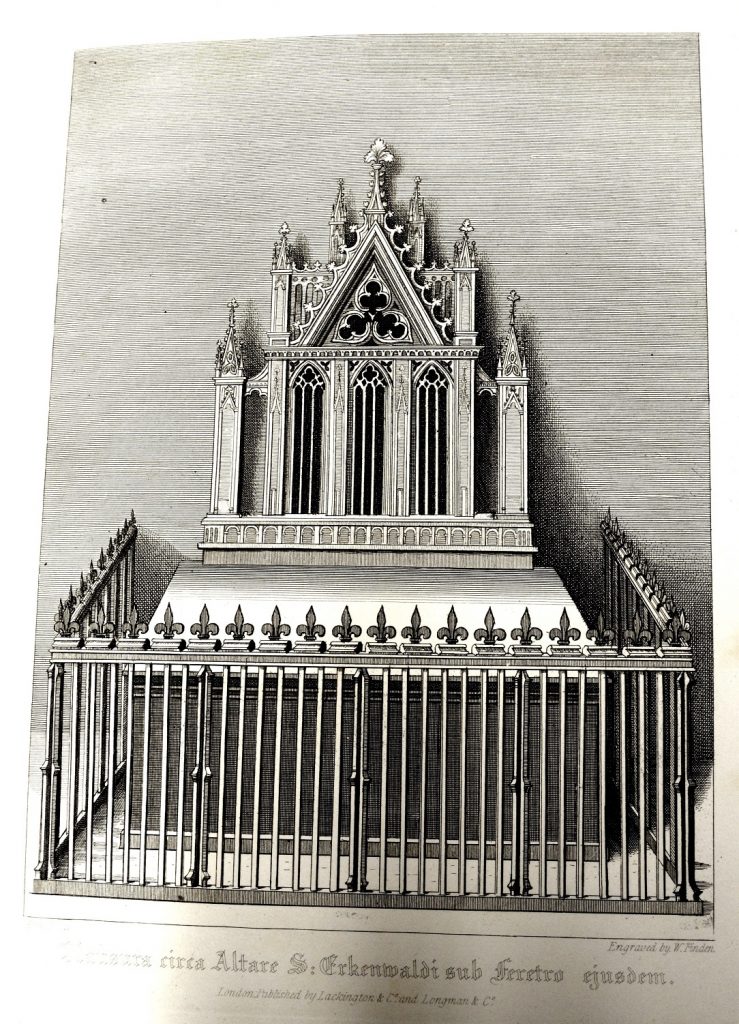

University of Leicester Special Collections. The Shrine of Saint Erkenwald, which was in the shape of a pyramid, with an offering-table before it, and was adorned with gold, silver and precious stones. From SCT 00908, William Dugdale, The History of St. Pauls Cathedral in London : From its Foundation Untill these Times …, (London, 1818).

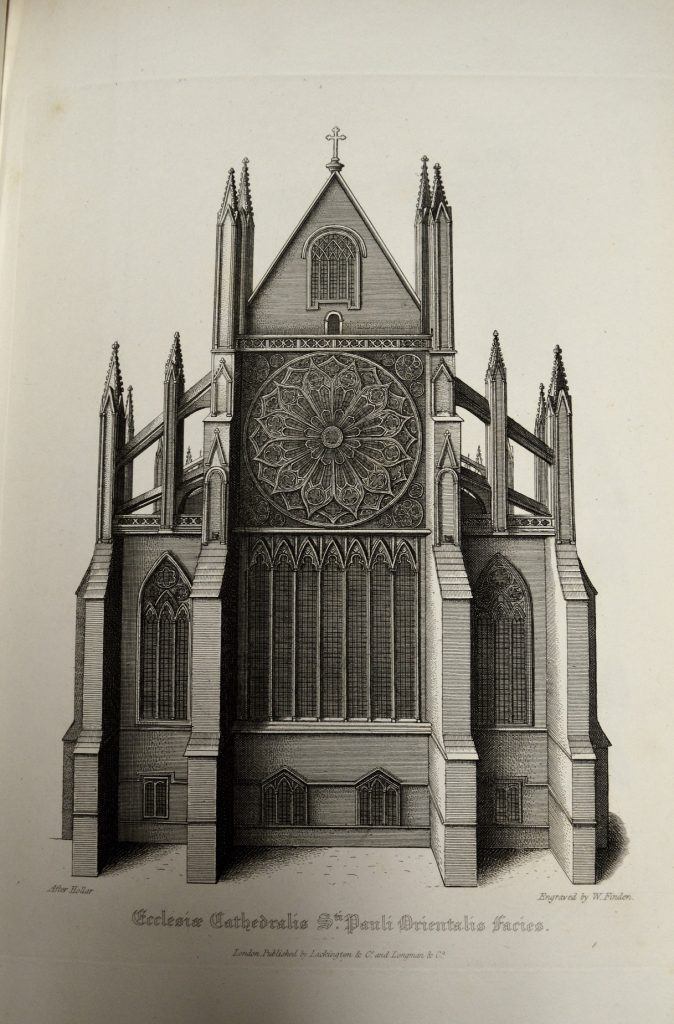

The old Cathedral’s greatest glory was the Shrine of St Erkenwald, a popular destination for medieval pilgrims. Many miracles were believed to have occurred, after petitioners visited the Shrine. Erkenwald, appointed Bishop of London in 675/6, died at Barking and a dispute arose between the clergy of St Paul’s and the monks of Barking as to where his body should lie. According to legend, a violent storm broke out and the River Lea flooded, but suddenly the sun broke through, pointing the way to St Paul’s via a golden path. In 1148, his body was moved from the crypt to a shrine behind the High Altar, inside the East Wall, which was composed largely of a series of spectacular stained glass windows, 7 tall lancets with a huge rose above, providing a dramatic backdrop. Katherine of Aragon made an offering at the Shrine two days before her marriage to Arthur, heir to the throne, in November 1501 in the Cathedral.

University of Leicester Special Collections. The East wall of Old St Paul’s, behind which St Erkenwald’s shrine was sited, with its magnificent rose stained glass window. From SCT 00908, William Dugdale, The History of St. Pauls Cathedral in London : From its Foundation Untill these Times …, (London, 1818).

Old St Paul’s housed the tombs of many influential figures from history – among them, Ethelred the Unready and the great portrait painter Van Dyck – and was the

University of Leicester Special Collections. Old St Paul’s, after the loss of its famous spire in the fire of 1561 from: SCT 00908, William Dugdale, The History of St. Pauls Cathedral in London : From its Foundation Untill these Times …, (London, 1818).

scene of dramatic and formative events – such as the Thanksgiving Service in 1588 attended by Elizabeth I, after her victory over the Armada. In 1561, there was another fire, this one most probably caused by a lightning strike, and the famous steeple was set alight, crashing through the roof of the nave. This disaster marked the beginning of the building’s decline. The roof was repaired, again in timber and lead, but the steeple was not rebuilt, and only 50 years later the work to the roof was found to have been shoddily carried out. During the Reformation, the Cathedral suffered further damage to its monastic buildings and ornament. Things reached their lowest point during the Civil War; Parliament seized the revenues of the Cathedral in 1643 and the nave was used as a cavalry barracks:

‘The conduct of the rough soldiers created great scandal. They played games, brawled and drank in the church, prevented people from going through the nave, and caused such grievous complaints, that an order was passed forbidding them to play at ninepins from six o’clock in the morning to nine in the evening.6’

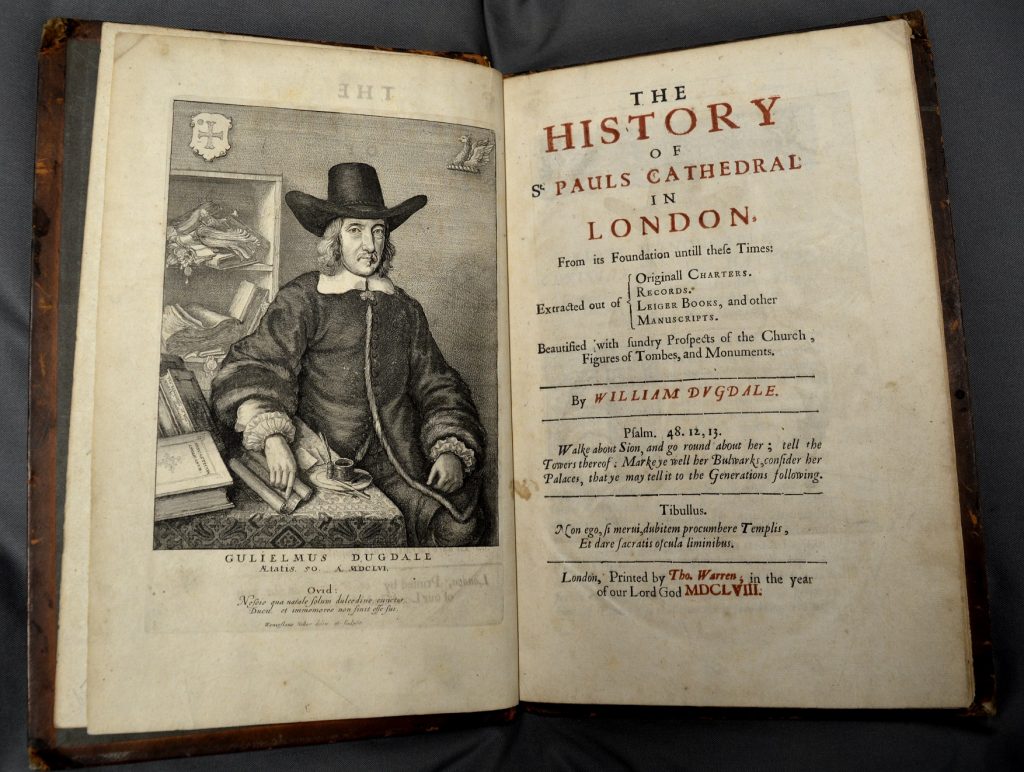

William Dugdale wrote his history of the Cathedral, during the Protectorate in 1658, because he feared that it might be destroyed altogether, ‘to the end, that by Inke and paper, the Shadows of [the principall Churches of this Realme], with their Inscriptions might be preserved for posteritie, forasmuch as the things themselves were so neer unto ruine’7.

University of Leicester Special Collections. Frontispiece and title page from: SCT 00907, William Dugdale, The History of St. Pauls Cathedral in London : From its Foundation Untill these Times …, (London, 1658).

After the Restoration, Christopher Wren was asked to survey the building. In May 1666, he proposed various works to repair and restore the body of the Cathedral, introducing more light, and to replace the truncated tower with a dome. Estimates for the work involved were ordered on Monday 27 August 1666, but only the following Sunday these plans were rendered superfluous by the onset of the Great Fire. Ironically, the wooden scaffolding erected around the Cathedral, so that repair works could be carried out, helped the fire take hold more quickly.

Five days after the outbreak of the Fire on 7 September, John Evelyn walked from Whitehall to London Bridge, passing by St Paul’s, ‘with extraordinary difficulty, clambering over heaps of yet smoking rubbish, and frequently mistaking where I was. The ground under my feete so hot, that it even burnt the soles of my shoes’. The scene that confronted him was desolate: ‘that goodly Church St. Paules now a sad ruine, and that beautiful portico … now rent in pieces, flakes of vast stone split asunder … It was astonishing to see what immense stones the heate had in a manner calcin’d, so that all the ornaments, columns, freezes, capitals, and projectures of massie Portland-stone flew off, even to the very roofe, where a sheet of lead covering a great space … was total mealted … Thus lay in ashes that most venerable Church, one of the most antient pieces of early piety in the Christian world.7′

- John Evelyn, Memoirs Illustrative of the Life and Writings of John Evelyn Esq. …, Vol. 1, (London, 1819), p. 393, SCT 00078

- William Benham, Old St Paul’s Cathdral, (London, 1902), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/16531/16531-h/16531-h.htm

- Ibid.

- John Earle, Micro-Cosmographie, (London, 1989), p. 73, FAIRCLOUGH SH.1.1 EAR

- P.H. Ditchfield, The Cathedrals of Great Britain, (London, 1902), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/43402/43402-h/43402-h.htm

- William Dugdale, The History of St. Pauls Cathedral in London : From its Foundation Untill these Times …, (London, 1658), Epistle Dedicatory p. 2, SCT 00907

- John Evelyn, Memoirs Illustrative of the Life and Writings of John Evelyn Esq. …, Vol. 1, (London, 1819), pp. 394-5, SCT 00078

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Dear Margaret,

I was wondering if it would be possible to use one of the images of Old St Paul’s for the cover of a CD of guitar music I’m hoping to compile and which would be for circulation amongst friends. If, so, what would be the right form of words for an acknowledgement?