Our current exhibition from the Special Collections, ‘”Strangers in the Land”? Impressions of India’, explores the attitudes and reactions of the British in India, from the early 17th century to the turn of the 20th, and the repercussions of a complex and fascinating relationship on the cultures of both countries. Many of the items displayed are from the Union Club Library, the contents of which were purchased by the University in 1964.

I was intrigued as to why this decision to purchase was taken and searched the Minutes of various University bodies around that date and any available correspondence relating to acquisitions for an answer. But, interestingly, in contrast to the Physical Society Library, which was also acquired around that time, I was unable to find any background information about the Union Club Library contents or arguments as to why the University should acquire it. Nor was I able to find any copies of correspondence between the Librarian or other University representatives and the Union Club. The key probably lies in the Library Board Minutes of 4 February 1964:

‘Professor Hughes had offered to contribute substantially to the purchase of the library of the Union Club in London, which was available for sale. This library contains about 3000 volumes of general literature and many of these would be very useful additions to the Library.’1

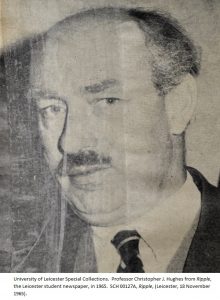

Professor Christopher Hughes, who came to Leicester as a Lecturer in Politics in 1957 and was appointed to the Chair of Politics in 1962, retiring in 1981, was a specialist in political theory. His family had a strong tradition of military service (he had, himself, served in an Indian Infantry Regiment during World War II and was held prisoner by the Japanese in Thailand for 3½ years, subjected to medical experiments and terrible conditions) and the Union Club counted many high-ranking military men amongst its members over the years – the Marquess of Hastings, who served as Governor-General of India from 1813, for example. The evidence suggests that Hughes was the driving force in bringing the Union Club books to Leicester and, from the Minutes, it certainly appears that he paid the lion’s share of the purchase-price.

Professor Christopher Hughes, who came to Leicester as a Lecturer in Politics in 1957 and was appointed to the Chair of Politics in 1962, retiring in 1981, was a specialist in political theory. His family had a strong tradition of military service (he had, himself, served in an Indian Infantry Regiment during World War II and was held prisoner by the Japanese in Thailand for 3½ years, subjected to medical experiments and terrible conditions) and the Union Club counted many high-ranking military men amongst its members over the years – the Marquess of Hastings, who served as Governor-General of India from 1813, for example. The evidence suggests that Hughes was the driving force in bringing the Union Club books to Leicester and, from the Minutes, it certainly appears that he paid the lion’s share of the purchase-price.

Hughes was most definitely a ‘character’, something of a maverick, who felt that a university should be populated by ‘gentlemen’, replaced his filing tray with a turkey dish and kept only a bottle of sherry and some glasses in his filing cabinet. ‘His colleagues and students often found it difficult to be sure whether his idiosyncratic statements and behaviour sprang from intrinsic mischievous eccentricity or whether he was acting a part to make a point’.2

An interview with Hughes in the Leicester student newspaper, Ripple, in 1965 gives an indication of his very individual approach to teaching and dry sense of humour. When asked for his assessment of the public image of students, he comments,

‘Some students indulge in playing at being working-class, refuse to adjust their attitudes to prepare themselves for becoming members of the professions, and sometimes only realise what has happened six months after they have left.’

And, when asked whether there are any changes in students’ attitudes, which he would like to see, he replies,

‘One must accept people as they are without criticism, you know. Students are likeable, intelligent, often without any particular merit, but I wouldn’t want to see them any different’3.

For anyone who would like to know more about Professor Hughes, the website of the Centre for Swiss Politics at the University of Kent has a section devoted to him, which includes a very informative account of his life and academic work https://www.kent.ac.uk/politics/cfs/csp/hughes.html .

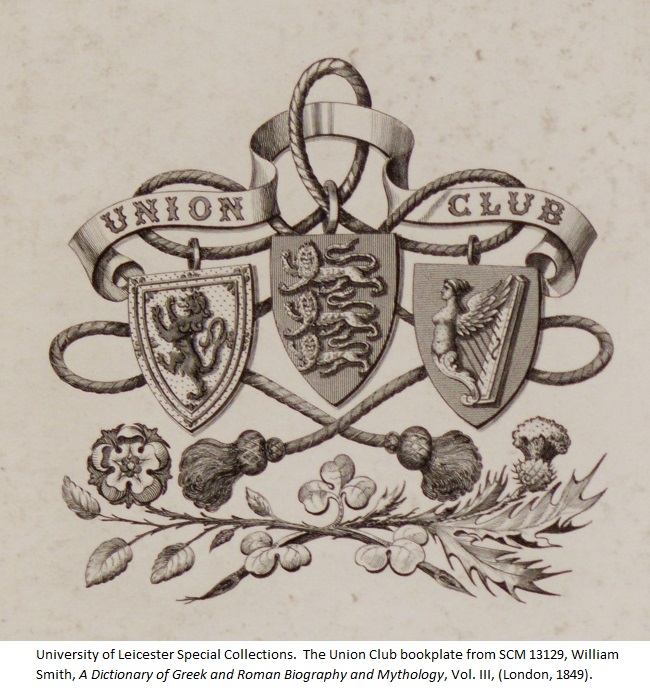

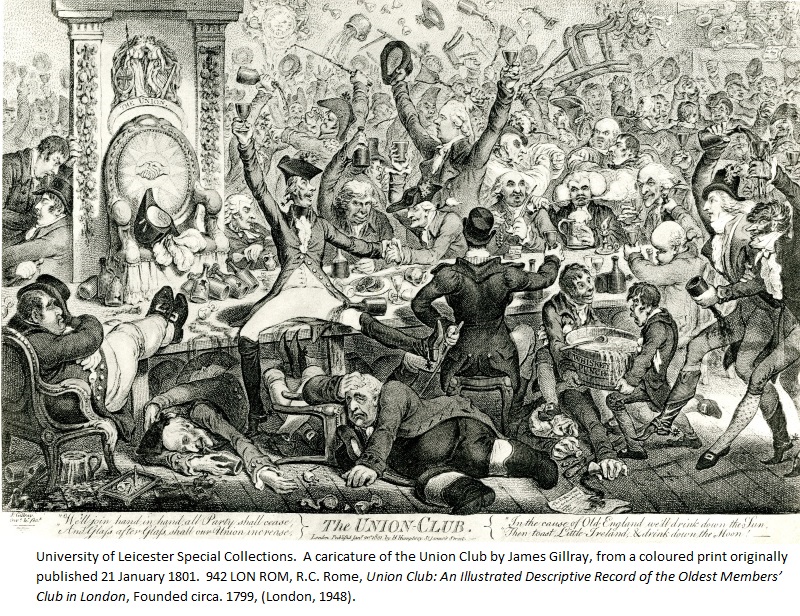

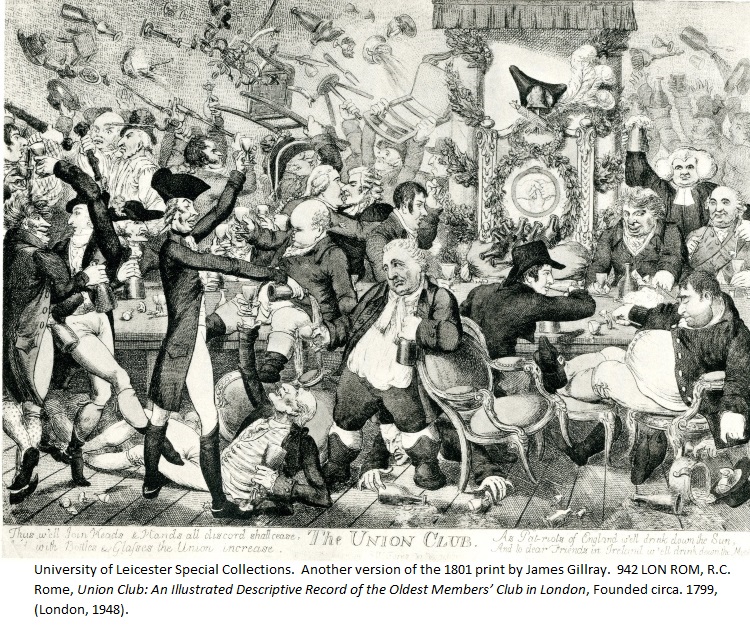

The Union Club referred to is not the present-day Union Club in Soho. It was a renowned gentlemen’s ‘haunt’, whose members included the likes of the Duke of  Wellington and Sir Robert Peel, as well as influential literary figures, such as Lord Byron and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Founded in 1799 or 1800, the Club’s original premises were at the Albion Hotel in Pall Mall. It moved to 21 St James’ Square and again, in about 1818, to a house in Regent Street, near Hanover Square. In 1821, the club was reconstituted by Colonel William Mayne and a new club-house, eventually opened in 1824, was built on the west side of what is now Trafalgar Square. This is now Canada House, which was bought by the Canadian government in 1923.

Wellington and Sir Robert Peel, as well as influential literary figures, such as Lord Byron and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Founded in 1799 or 1800, the Club’s original premises were at the Albion Hotel in Pall Mall. It moved to 21 St James’ Square and again, in about 1818, to a house in Regent Street, near Hanover Square. In 1821, the club was reconstituted by Colonel William Mayne and a new club-house, eventually opened in 1824, was built on the west side of what is now Trafalgar Square. This is now Canada House, which was bought by the Canadian government in 1923.

R.C. Rome’s history of the Union Club’s early days4 gives many revealing details of the furnishing and running of the clubhouse. Initially, smoking was forbidden, but snuff and alcohol were readily available and, no doubt, liberally consumed whilst playing whist, écarté and picquet, the popular card games of the day. In 1824, sweet champagne was sold for half a guinea a bottle and the Bond Street butcher, who supplied the club with beef, mutton and veal for 6½d. per lb. and rejoiced in the name of Mr Giblet, had his contract terminated for ‘abusing the good will of the Committee’5. But also in the same year, £263 6s. 9d. (a considerable sum, about a tenth of that spent on furnishing the new clubhouse) was spent on books for the library and a special subscription of one guinea from each member towards the stocking and running of the library was instituted. Rome also relates a number of anecdotes, which evoke the club’s very particular atmosphere – spats between individual members, problems with the staff, even a scandal over attempts to rig a ballot of members in 1828. I can’t help singling out the outrage caused in March 1846 by Sir Charles Thornton ‘spitting in the milk jug’, while taking breakfast. When asked by the Committee to explain himself, he ‘blandly admitted the correctness of the accusation, but refused to give any explanation whatever’6!

R.C. Rome’s history of the Union Club’s early days4 gives many revealing details of the furnishing and running of the clubhouse. Initially, smoking was forbidden, but snuff and alcohol were readily available and, no doubt, liberally consumed whilst playing whist, écarté and picquet, the popular card games of the day. In 1824, sweet champagne was sold for half a guinea a bottle and the Bond Street butcher, who supplied the club with beef, mutton and veal for 6½d. per lb. and rejoiced in the name of Mr Giblet, had his contract terminated for ‘abusing the good will of the Committee’5. But also in the same year, £263 6s. 9d. (a considerable sum, about a tenth of that spent on furnishing the new clubhouse) was spent on books for the library and a special subscription of one guinea from each member towards the stocking and running of the library was instituted. Rome also relates a number of anecdotes, which evoke the club’s very particular atmosphere – spats between individual members, problems with the staff, even a scandal over attempts to rig a ballot of members in 1828. I can’t help singling out the outrage caused in March 1846 by Sir Charles Thornton ‘spitting in the milk jug’, while taking breakfast. When asked by the Committee to explain himself, he ‘blandly admitted the correctness of the accusation, but refused to give any explanation whatever’6!

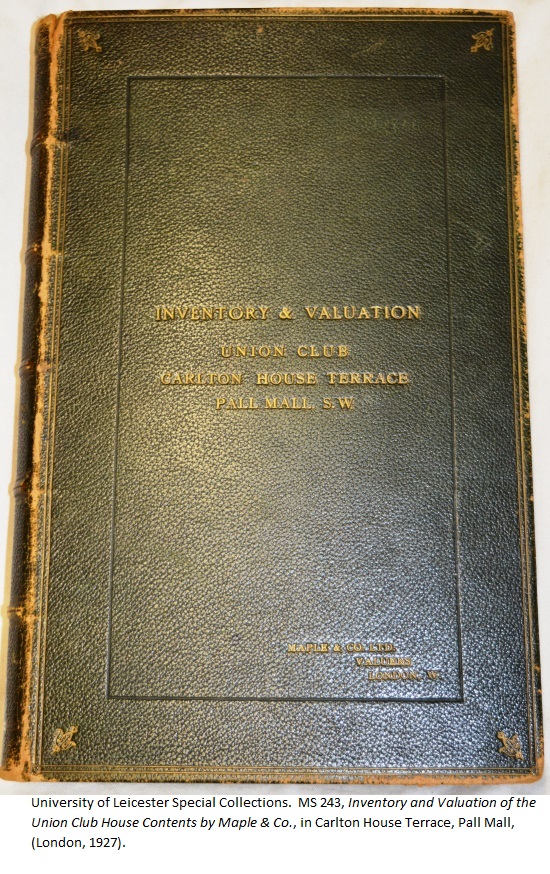

The club apparently moved to 86 St James Street until the 1960s (although its history must have been more complicated than this, as our MS 243, Inventory and Valuation of the Club House Contents by Maple & Co., 1927, gives the address as Carlton House Terrace, Pall Mall). In the 1960s, it merged with the United Service Club at 116 Pall Mall (a club for senior army and navy officers). It seems that this merger may have been the trigger for the sale of the library contents. The United Service Club, too, closed in 1978.

As well as the many printed volumes from the Union Club Library now housed in the Special Collections and the Inventory of 1927 mentioned above, which is on display in the exhibition, we hold a number of Union Club Library catalogues, subject indexes and lists of acquisitions. Amongst our Deposited Collections is D7, The C.J. Hughes Collection, which contains papers concerning Professor Hughes’ tenure as Head of Politics, teaching notes, correspondence with colleagues and papers of staff seminars.

The exhibition runs until 30 September 2016 in the basement of the David Wilson Library. Entry to the library is free but controlled, so if you are not a student or member of University staff, please ask to be let through the barrier. Details of staffed opening hours are available on the library website.

1Minutes of the Library Board, 4 February 1964, 21 (d) Gifts, M47/2

2Obituary for Professor Christopher Hughes by John Day, http://www.le.ac.uk/ebulletin-archive/ebulletin/people/bereavements/2000-2009/2006/03/nparticle-mwd-dtv-ykd.html

3Ripple, (Leicester, 18 November 1965), p. 10, SCH 00127A

4R.C. Rome, Union Club: An Illustrated Descriptive Record of the oldest Members’ Club in London, Founded Circa 1799, (London, 1948), 942 LON ROM

5Ibid. p. 19

6Ibid. p. 38

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Recent Comments