Our current exhibition, ‘”Strangers in the land”? Impressions of India’ traces the history of the British in India from the early 17th century to the turn of the 20th. Some always remained, in the words of the Governor of Madras in 1807, ‘strangers in the land’; others, like the free-thinker and theosophist Annie Besant, who first visited India in 1893, embraced the religion and customs of the country, ‘living in Indian fashion, feeling with Indian feelings’; and there were all shades in between. The selection of 17th-19th century publications on display demonstrates that ‘the nature of British dominion was shaped by Indian as much as by British people, and as much by their cooperation as by their resistance’1.

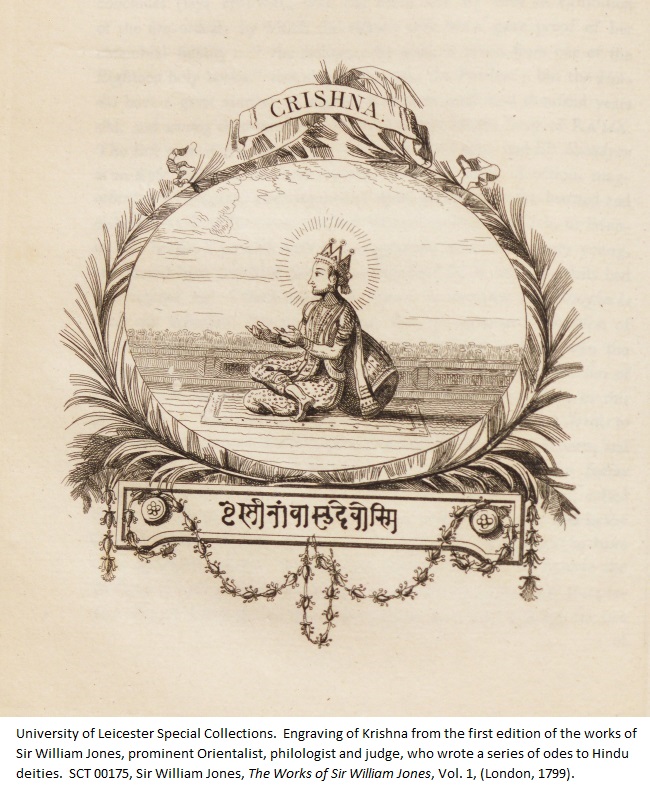

Unlike Besant, many of the British found it almost impossible to comprehend Hinduism, with its profusion of gods and goddesses and lack of dogma. As early as 1627, Sir Thomas Herbert, in spite of his delighted fascination with the strict vegetarian caste of ‘banyans’, Hindu merchants from Surat, mistakenly concluded that they ‘worshipp the Devil, in sundry shapes and representations’2. Later, the activities of Christian missionaries in the East India Company’s territories and attempts at social reform (the curbing of the practice of suttee for example) were perceived as attempts to interfere in Indian religion and customs and contributed to the widespread discontent, which erupted in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Even in the incident which triggered this ‘Mutiny’ (cartridges on the new Enfield rifles, which had to be bitten off by the Indian sepoys, were rumoured to be greased with pig and cow fat), the British demonstrated an extreme lack of sensitivity to both Muslim and Hindu sensibilities.

Later, the activities of Christian missionaries in the East India Company’s territories and attempts at social reform (the curbing of the practice of suttee for example) were perceived as attempts to interfere in Indian religion and customs and contributed to the widespread discontent, which erupted in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Even in the incident which triggered this ‘Mutiny’ (cartridges on the new Enfield rifles, which had to be bitten off by the Indian sepoys, were rumoured to be greased with pig and cow fat), the British demonstrated an extreme lack of sensitivity to both Muslim and Hindu sensibilities.

Sati (or suttee), self-immolation by a widow on the funeral pyre of her husband, originally perceived as a saintly and heroic act, became for some British ‘the imperial exemplar for all that was wrong with the land and its people’3. The exhibition looks at different shades of opinion on how best to deal with the practice of sati and the problem of thuggee. But, sadly, lack of space prevented me from including any discussion of another event, which became the focus of much moral indignation among the British, the festival of ‘Juggernath’.

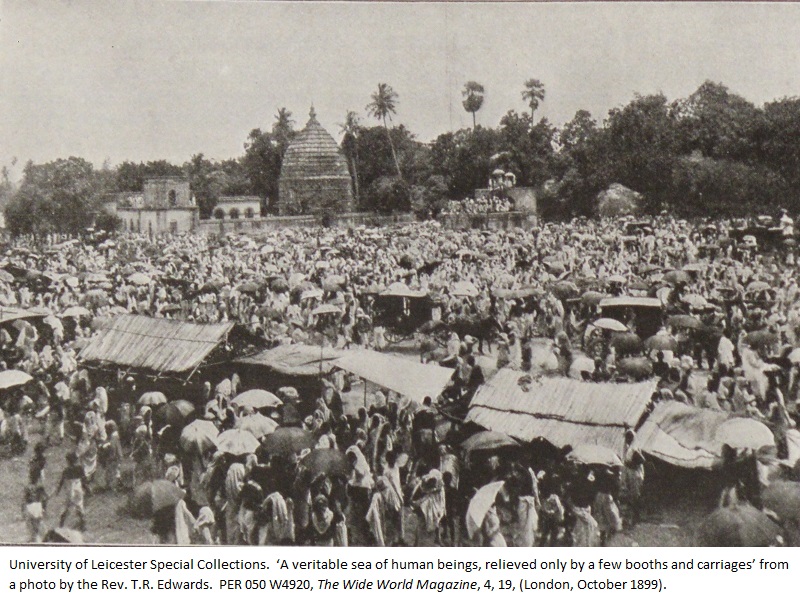

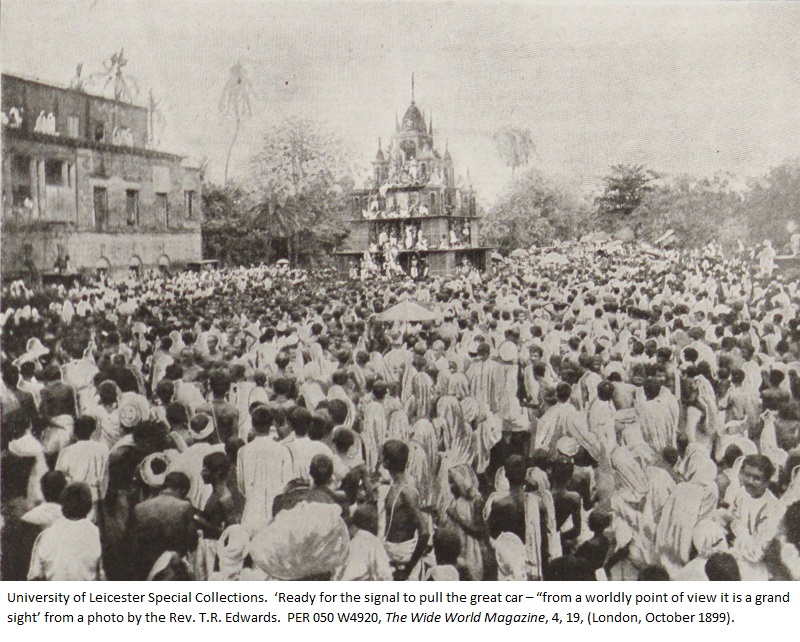

The oldest and best known centre of the worship of Jagganath, an ancient form of Vishnu, is at Puri on the east coast, which is considered one of the most sacred Hindu pilgrimage sites in India. Here, once a year in June/July, in the Rath Yatra festival, the idols of Jagganath and his siblings are brought out of the temple and pulled by devotees on massive wooden chariots to a neighbouring temple. From this custom, of course, we derive the word ‘juggernaut’, a huge, unstoppable force which crushes all in its path. In the 14th century, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville described pilgrims throwing themselves under the wheels of the chariot in a frenzy of devotion, ‘they believe that the more pain they suffer here for the love of that idol, the … nearer God they will be’4. However, little is known about the identity of the author of these travels, even whether he actually travelled at all, and, in his destinations, he also encounters dog-headed men or, in India, a miraculous Well of Youth and yellow and green people on the banks of the Indus! Whether or not there was any truth in such accounts, or whether any deaths were instead caused accidentally by the volume and press of the crowd, such horrors were widely believed and on 15 August 1864 The Times’ correspondent in India sent the following eye-witness account:

The oldest and best known centre of the worship of Jagganath, an ancient form of Vishnu, is at Puri on the east coast, which is considered one of the most sacred Hindu pilgrimage sites in India. Here, once a year in June/July, in the Rath Yatra festival, the idols of Jagganath and his siblings are brought out of the temple and pulled by devotees on massive wooden chariots to a neighbouring temple. From this custom, of course, we derive the word ‘juggernaut’, a huge, unstoppable force which crushes all in its path. In the 14th century, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville described pilgrims throwing themselves under the wheels of the chariot in a frenzy of devotion, ‘they believe that the more pain they suffer here for the love of that idol, the … nearer God they will be’4. However, little is known about the identity of the author of these travels, even whether he actually travelled at all, and, in his destinations, he also encounters dog-headed men or, in India, a miraculous Well of Youth and yellow and green people on the banks of the Indus! Whether or not there was any truth in such accounts, or whether any deaths were instead caused accidentally by the volume and press of the crowd, such horrors were widely believed and on 15 August 1864 The Times’ correspondent in India sent the following eye-witness account:

‘At last the mob happened to pull together instead of one after the other, and the huge mass moved forward a few yards, groaning as if it had been a living creature. It stopped and for a few minutes the crowd stood in almost perfect silence. Then the Brahmins again gave the signal, and this time it crushed out a life with every revolution of its hideous wheels, covered as they were with human flesh and gore … I … saw upon the ground a very old woman, all wrinkled and puckered up, with scarcely a lineament of her face recognizable for blood and dust. Her right foot was hanging by a thread, the wheels had passed over the centre of her nearly naked body, and a faint quiver of anguish ran through her frame as she seemed to struggle to rise’5.

It stopped and for a few minutes the crowd stood in almost perfect silence. Then the Brahmins again gave the signal, and this time it crushed out a life with every revolution of its hideous wheels, covered as they were with human flesh and gore … I … saw upon the ground a very old woman, all wrinkled and puckered up, with scarcely a lineament of her face recognizable for blood and dust. Her right foot was hanging by a thread, the wheels had passed over the centre of her nearly naked body, and a faint quiver of anguish ran through her frame as she seemed to struggle to rise’5.

The Spectator, picking up on this account on 20 August, was moved to attack ‘dreamy epics’ about the romance and mystery of the East so popular in Victorian times and to contrast them unfavourably with this ‘minute, carefully toned account of the keen-eyed correspondent’, condemning Hinduism as ‘a faith utterly base as well as evil’. ‘The Government of India,’ it thunders, ‘is bound to be tolerant of many things forbidden by English feeling, and compelled to tolerate many more forbidden by English morals, but human sacrifices to idol deities cannot be permitted within the limits of a British dependency’6.

And indeed, by the time we reach October 1899, the Rev. T.R. Edwards of the Baptist Missionary Society (whose intriguing photos are shown here) was able to write in The Wide World Magazine, in reference to ‘the sanguinary horrors of the festival and the hideous trail of blood left by the murderous wheels’ (which, tellingly, he says had been described in ‘the reading-books we used at school’):

‘All this is past and gone, thanks to the beneficent rule of the British in India’7.

The British magistrate was now present at the festival, along with a large contingent of police and an officer with a gun, ‘the firing of which is understood by all to mean that the pulling must instantly cease’.

The exhibition runs until 30 September 2016 in the basement of the David Wilson Library. Entry to the library is free but controlled, so if you are not a student or member of University staff, please ask to be let through the barrier. Details of staffed opening hours are available on the library website.

1C.A. (Christopher Alan) Bayly, The Raj: India and the British, 1600-1947, (London, 1990), p. 11, 954.03 RAJ

2Sir Thomas Herbert, A Relation of Some Yeares Travaile, Begunne Anno 1626: Into Afrique and the Greater Asia …, (London, 1634), ‘An Indian Merchant or Bannyan’ pp. 37-8, SCM 09672

3Hermione De Almeida, Indian Renaissance: British Romantic Art and the Prospect of India, (Burlington, Vt., 2005), p. 229, 709.42 DE

4Sir John Mandeville, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, (London, 1983), pp. 125-6, 915.042 MAN

5’India’, The Times, (15 August 1864), The Times Digital Archive

6’The Festival of Juggernath’, The Spectator, (20 August 1864), p. 11, The Spectator Digital Archive

7The Wide World Magazine, 4, 19, (October 1899), p. 25, PER 050 W4920

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Recent Comments