For all the Easter traditions that have been passed down to us over the centuries, there are a few that are have fallen by the wayside. Writing on the subject of “Ancient Customs” in the July 1783 issue of the Gentleman’s Magazine, the correspondent H.T. noted,

A custom, which ought to be abolished as improper and indecent, prevails in many places, of lifting as it is called, on Easter Monday and Tuesday. (PER 050 G0344, p. 578)

According to J. H—y of Manchester, writing the following February, this custom was ‘originally designed to present our Saviour’s resurrection’.

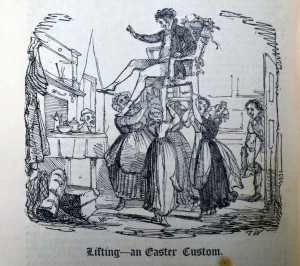

There are several references to “lifting” or “heaving” in Special Collections, including in William Hone’s popular Every-Day Book; or Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements (London, 1826 ed.). According to Hone, the practice was common in Lancashire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire and other parts of England. Groups of people would gather together in the street and physically lift those they came across into the air, expecting a financial reward in return. Hone describes the practice as differing slightly in different parts of the country:

In some parts the person is laid horizontally, in others placed in a sitting position on the bearers’ hands. Usually, when the lifting or heaving is within doors, a chair is produced, but in all cases the ceremony is incomplete without three distinct elevations. (SCM 03706, p. 426)

In Warwickshire, Easter Monday and Easter Tuesday were known as ‘heaving-day‘, because on the Monday it was the tradition for men to ‘heave and kiss the women’ and on the Tuesday for the women to do the same to the men. Hone viewed the practice as, ‘an absurd performance of the resurrection’ derived from the Catholic church.

A more detailed account of heaving was first printed in Henry Ellis’s edition of John Brand‘s Observations on Popular Antiquities (London, 1813), vol. 1. The description was from Thomas Loggan, a ‘correspondent of great respectability’, who encountered the practice while minding his own business eating breakfast at the Talbot Inn, Shrewsbury. A group of female servants entered, carrying a chair lined in white decorated with multi-coloured ribbons. When asked what they wanted, they replied that they came to “heave” him, according to custom:

It was impossible not to comply with a request very modestly made, and to a set of nymphs in their best apparel, and several of them under twenty. I wished to see all the ceremony, and seated myself accordingly. The groupe then lifted me from the ground, turned the chair about, and I had the felicity of a salute from each. I told them, I supposed there was a fee due upon the occasion, and was answered in the affirmative; and having satisfied the damsels in this respect, they withdrew to heave others. (SCM 09950, pp. 155-56)

The most recent scholarly account of ‘heaving’ can be found in Ronald Hutton’s Stations of the Sun: A History of the ritual Year in Britain (Oxford, 1996), pp. 211-213. Hutton comments that experiences like that of Thomas Loggan represented a reversal of the usual balance of power between the classes and genders. The practice appears to have been at its height in the eighteenth century, and was in decline by the early nineteenth. It persisted in some areas for a little longer, for example at Bakewell in Derbyshire where young men lifted and kissed the girls on Easter Monday as late as the 1890s. After this it seems to have died out altogether, although during the last few years there has been an attempted revival in Greenwich, where the Blackheath Morris Men have taken it upon themselves to start lifting and heaving once more!

Subscribe to Simon Dixon's posts

Subscribe to Simon Dixon's posts

Recent Comments