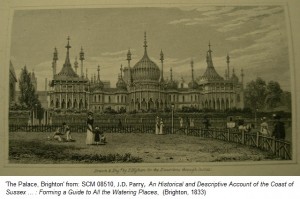

‘The Palace, Brighton’ from: SCM 08510, J.D. Parry, An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Coast of Sussex … : Forming a Guide to All the Watering Places, (Brighton, 1833)

Prompted both by some research I am doing for an

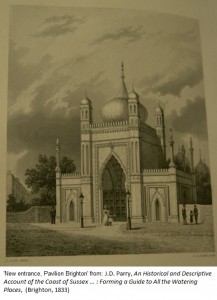

‘New entrance, Pavilion, Brighton’ from: SCM 08510, J.D. Parry, An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Coast of Sussex … : Forming a Guide to All the Watering Places, (Brighton, 1833)

exhibition on the early history of the British in India and by a recent visit to the extraordinary Brighton Pavilion (in which, of course, the ‘Mogul’ style is very much in evidence) , I wanted to investigate some 19th century reactions to the building, as demonstrated by Leicester’s Special Collections. The Pavilion has always caused controversy, described variously as ‘silly, charming, witty, light-hearted, extravagant, gloriously eccentric, decadent, childish, painfully vulgar, socially irresponsible’1. Although we perhaps tend to think of it as the ultimate flowering of ‘Chinoiserie’, in fact it is a Romantic confection of ‘Oriental’ styles, encompassing the Far East and the Middle East – Indian, Egyptian, Chinese – together with the Gothic, a sort of exotic stage-set for the Prince Regent, later George IV’s seaside entertaining.

![Plate illustrating the delights of Sussex, including Brighton Pavilion. From: SCM 06517, Reuben Ramble, pseud., Reuben Ramble’s Travels Through the Counties of England, (London, [1845?])](https://staffblogs.le.ac.uk/specialcollections/files/2015/12/SCM06517p12amended.jpg)

Plate illustrating the delights of Sussex, including Brighton Pavilion. From: SCM 06517, Reuben Ramble, pseud., Reuben Ramble’s Travels Through the Counties of England, (London, [1845?])

![‘His Majesty’s Palace, Brighton’ from: SCS 02537, John Baxter, publisher, The Stranger in Brighton, and Baxter’s New Brighton Directory, (Brighton, [1822])](https://staffblogs.le.ac.uk/specialcollections/files/2015/12/SCS02537pxxiiamended-300x218.jpg)

‘His Majesty’s Palace, Brighton’ from: SCS 02537, John Baxter, publisher, The Stranger in Brighton, and Baxter’s New Brighton Directory, (Brighton, [1822])

The significance of the Pavilion’s Indian elements was immediately obvious to J.D. Parry in 1833: ‘The general aspect of this front is rather Indian or Persian than Chinese … It also recalls to us one branch of that mighty continental influence which we wield, it may be hoped and trusted for the general happiness and benefit. The King of England is almost ‘de facto’ King of India … why should he not have his Oriental Marine Pavilion’4. It seems that George felt ‘it was part of his role to dramatize national and imperial glory and status both in his person and in his palaces’5.

![‘Pavilion at Brighton’ from: SCS 02546, John Bruce, The History of Brighton with the Latest Improvements to 1835, (Brighton, [1835])](https://staffblogs.le.ac.uk/specialcollections/files/2015/12/SCS02546p25amended.jpg)

‘Pavilion at Brighton’ from: SCS 02546, John Bruce, The History of Brighton with the Latest Improvements to 1835, (Brighton, [1835])

![Frontispiece and title page from: SCS 04822, The Visit to Brighton, or, Amusement & Information Combined, (London, [183-?])](https://staffblogs.le.ac.uk/specialcollections/files/2015/12/SCS04822frontamended.jpg)

Frontispiece and title page from: SCS 04822, The Visit to Brighton, or, Amusement & Information Combined, (London, [183-?])

![‘South Entrance to the Palace’, ‘North Entrance to the Palace’ and ‘Southern Front of the Royal Mews’ from: SCS 02547, The Stranger's Guide in Brighton …, (Brighton, [1844?])](https://staffblogs.le.ac.uk/specialcollections/files/2015/12/SCS02547p11amended.jpg)

‘South Entrance to the Palace’, ‘North Entrance to the Palace’ and ‘Southern Front of the Royal Mews’ from: SCS 02547, The Stranger’s Guide in Brighton …, (Brighton, [1844?])

The Pavilion is just one manifestation of the Regency fascination with the magnificence and mystery of India, which spilled out into scholarship, literature and poetry as well as architecture, art and design and which I hope to explore further in an exhibition later in 2016.

- Open Learn, The Open University, http://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/history-art/brighton-pavilion/content-section-0

- SCT 01367, Mark Antony Lower, The Worthies of Sussex …, (Lewes, 1865), p. 60.

- SCM 08514, James Rouse, The beauties and antiquities of the county of Sussex … , (London, 1825), p. 242

- SCM 08510, J.D. Parry, An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Coast of Sussex … : Forming a Guide to All the Watering Places, (Brighton, 1833), pp. 114-6

- Open Learn, The Open University, http://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/history-art/brighton-pavilion/content-section-5

- SCS 02547, The Stranger’s Guide in Brighton …, (Brighton, [1844?]), p. 11

- SCS 04822, The Visit to Brighton, or, Amusement & Information Combined, (London, [183-?]), p. 30

- SCS 02539, Brighton as it is, 1834 …, (Brighton, 1834), pp. 14-5

- SCM 06517, Reuben Ramble, pseud., Reuben Ramble’s Travels through the Counties of England, ([London], [1845?]), p. 12

- SCS 05477, George Measom, The Official Illustrated Guide to the Brighton and South Coast Railway and its branches …, (London, [c. 1855]), pp. 68-9

- SCM 08510, J.D. Parry, An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Coast of Sussex … : Forming a Guide to All the Watering Places, (Brighton, 1833), pp. 115-6

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.