In spite of all the Hypochondriac’s attempts to keep sickness at bay, Death comes whizzing down the chimney in the form of a skeletal spider. The Hypochondriac’s cat remains unmoved. Richard Dagley, ‘Death’s Doings’, (London, 1827), pl. opp. p. 150

While working on some book moves we are presently carrying out, I rediscovered the rather wonderful Death’s Doings illustrated by Richard Dagley, first published in 1822. This volume belongs to a long tradition on the Dance of Death theme, which dates back to medieval times, when death from war and violence, disease, poverty, childhood mortality and so on was an ever-present threat and people were all-too-familiar with the sight of a corpse. Sometimes the message given out by frescoes and drawings in this tradition seems to be that Death is the great leveller so you may as well enjoy yourself while you can, and sometimes it is an injunction to live a good life avoiding vices such as drunkenness and gluttony – or Death will seize you all the sooner. But all share the same macabre humour.

Very little has been written about Dagley, but 2 obituaries for him appeared in 1841 in The Art-Union and The Gentleman’s Magazine*, the first of these a lengthy tribute by Mrs B. Hofland of Hammersmith, who writes that she was a close friend of the artist and his family for 32 years. Death’s Doings, she tells us, was ‘suggested by Holbein’s Dance of Death’. First published in 1538 as Les Simulachres & historiées faces de la Mort, this hugely successful work made Hans Holbein the Younger’s name. Holbein’s genius was to portray a series of people from all walks of life – the King and Queen, even the Pope, but also the Pedlar, the

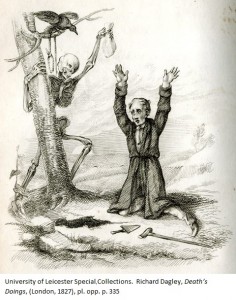

Dagley’s Miser scrabbles to dig up the treasure he has hidden beneath a tree – but Death has already claimed the bag of gold, which he holds up triumphantly. Richard Dagley, ‘Death’s Doings’, (London, 1827), pl. opp. p. 335

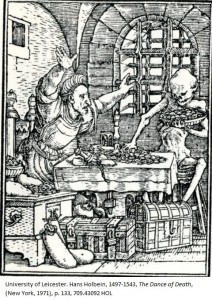

Death helps himself to handfuls of the Miser’s gold. Hans Holbein, 1497-1543, ‘The Dance of Death’, (New York, 1971), p. 133, 709.43092 HOL

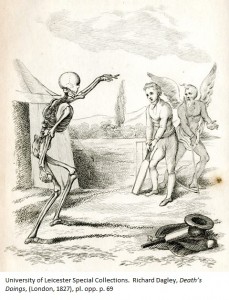

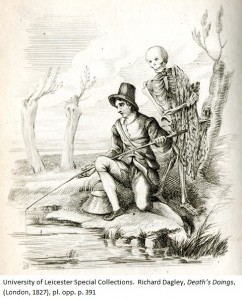

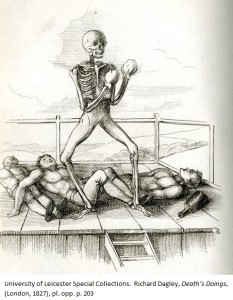

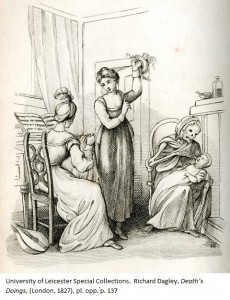

Ploughman and the Miser (shown here) – all summoned by Death in the midst of their usual daily activities. Dagley uses the same device, but his humour has a light touch and the scenes are very much of the 19th rather than the 16th century. So, like Holbein, he portrays the Miser, but we also have the Cricketer, the Boxer and the Angler. Dagley’s Death, rather than being simply a menacing phantom, is very definitely a ‘character’. His limbs are so flexible and rounded as almost to suggest they are flesh-clad, with glee he adopts a variety of contemporary costumes and accessories, his features compose themselves into a whole range of expressions.

Mrs Hofland writes that Dagley, along with his two brothers, was orphaned very young and placed in Christ’s Hospital. ‘Having a decided taste for fine art and being a delicate child’, he was then apprenticed to

Death is not only about to bowl to the hapless Cricketer, but he also seems to be deciding on the field placings. Richard Dagley, ‘Death’s Doings’, (London, 1827), pl. opp. p. 69

a jeweller and watchmaker called Cousins, where for a time he made a secure living enamelling miniature scenes. He also married one of Cousins’ daughters before he was ‘of age’, perhaps not the most level-headed decision by her father, as Dagley clearly was in no position to provide comfortably for a family.

Death lurks behind the Angler’s shoulder, seemingly about to trap him in a fishing net. Richard Dagley, ‘Death’s Doings’, (London, 1827), pl. opp. p. 391

When miniatures in jewellery and watches went out of fashion, he was forced to seek employment elsewhere, as a drawing master at a school in Doncaster. Unfortunately the proprietress seems to have

Death takes on all comers in the ring. The Champion from: Richard Dagley, ‘Death’s Doings’, (London, 1827), pl. opp. p. 203

lacked any business acumen, the venture ended in financial disaster and Dagley returned to London. In fact, Mrs Hofland paints a positively Dickensian picture of the family circumstances: Dagley a man of ‘fine taste and unremitting industry’, Mrs Dagley a woman ‘whom to know was to love’, clearly devoted to each other, the 10 children of their union all dead in infancy barring one daughter, ‘long seasons of anxiety and painful prospects of poverty … hover[ing] like demons o’er the dwelling’. Like many of his fellow artists, Dagley died virtually destitute – ‘(aged and shadowy as he was) [he] walk[ed] miles and miles, taxing mind and means to their utmost’ to support his family and assist his friends and neighbours.

As well as being an engraver, Dagley was an accomplished water-

Would you entrust your baby to this nurse? The Mother from: Richard Dagley, ‘Death’s Doings’, (London, 1827), pl. opp. p. 137

colour painter, exhibiting at the Royal Academy over a period of 40 years (mainly domestic scenes) and at the British Institution. He wrote many reviews of works of art and two books on gems. Along with Takings; Or, The Life Of A Collegian, illustrations to a humorous poem by Thomas Gaspey, published in 1821, Death’s Doings was his most successful work and the one for which he is best remembered.

*The Art-Union, Vol. III, 15 May 1841, pp. 86-7, PER 700 A8234 & The Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol. 15, June 1841, pp. 664-5, PER050 G3044

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Recent Comments