In 1627, at the age of only 21, Sir Thomas Herbert travelled to Persia and India as a low-ranking member of Charles I’s embassy to Shah Abbas I.

Frontispiece from: Sir Thomas Herbert, A relation of some yeares travaile, begunne anno 1626 …, (London, 1634), SCM 09672.

Frontispiece from: Sir Thomas Herbert, Some years travels into divers parts of Africa and Asia the Great …, (London, 1677), SCT 00254

His account of his experiences, Some Years Travels into Divers Parts of Africa and Asia the Great …, first published in 1634, was a great success and several later editions, with extensive additions, appeared during his lifetime. Herbert’s narrative is full of interesting details and digressions and the spontaneity, enthusiasm and humour in his writing must have been instrumental in the book’s popularity. In addition to the first edition, the Special Collections holds copies of the 1665 and 1677 editions.

Herbert vividly describes the hardships of his party’s journey by camel across the Parthian desert to the Caspian Sea:

‘We journied towards … Hircania … travelling all the night and reposing (I cannot say sleeping, the Gnats so troubled us) all the day. We had guides and a Convoy to direct us, the Starres were theirs, without whose ayme there is no certaintie. The Sunne is so fiery and makes the Sands so scalding on the day time, that it then prohibits Pilgrimages … The sands by the fury of Tempests lie in great drifts, like mountaines. So light and unstable, that the high ways are never certaine …’1

The embassy crossed a salt desert, ‘not unlike pure Snow … so deepe and boggie’2 that camels would sink and be buried, if they strayed from the causeway. They climbed the mountain of Damoan, from the top of which they could see the Caspian Sea 180 miles distant: ‘Tis above composed of Sulphur, which makes it in the night sparkle … tis so offensive to mount up, that you cannot doe it without a Nose-gay of strong Garlicke …’3

These trials had an adverse effect on the health of even the robust young Herbert (the adventurer Sir Robert Sherley, who accompanied the embassy, and its leader Sir Dodmore Cotton both died in Persia). Herbert, though suffering from dysentery, was ‘forced to travel 300 miles, hanging upon a Camell’ and his servant, ‘an old Tartarian Hecate’ tried to poison him:

‘Abbas King of Persia’ from: Sir Thomas Herbert, Some years travels into divers parts of Africa and Asia the Great …, (London, 1677), p. 216, SCT 00254

‘Shee knew strong drinke was utterly forbid me, for feare of inflammation, yet forced by inordinate thirst to call for water, she returnes me old intoxicating Shiraz Wine, which insensibly I powred downe, and … it … put mee for foure and twentie houres into a deadly trance.’4

While he lay in this stupor, the servant stole linen and money from his trunk and fled. Herbert, however, did not pursue her, because he did not want her to undergo the brutal punishments he had witnessed the Persians carry out on others.

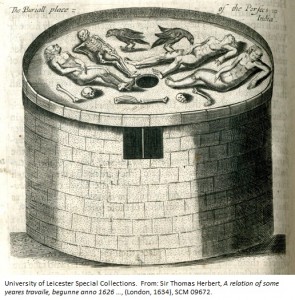

‘The Buriall Place of the Persees in India’ from: Sir Thomas Herbert, A relation of some yeares travaile, begunne anno 1626 …, (London, 1634), p. 40, SCM 09672

The book is rich with incisive little pen-portraits of the people Herbert encountered – Shah Abbas was ‘low of stature … fiery eyes, his nose long and hooked … his Mustachoes very long and bending downwards’.5 Herbert was intrigued by the exotic customs and practices he witnessed, Zoroastrian burial rites, for example, where the naked corpse was laid on top of a burial tower ‘exposed to the Sunnes fiery rage and devouring appetites of Vultures and Cormorants’. Herbert comments that these rites are ‘better to be spoken of, than seene’.6

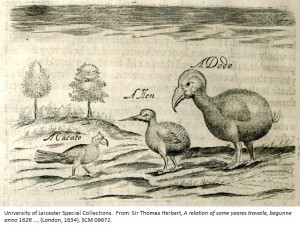

He gives us colourful descriptions of the local flora and fauna. In the  waters by the Canary Islands lurk ‘sharkes, whose cruell appetite[s] encourage them to devoure men alive. They are always directed by a little specled fish, called a pilot fish, by guiding their Monster-masters to a prey.’7 In Mauritius, he watched the Dodo:

waters by the Canary Islands lurk ‘sharkes, whose cruell appetite[s] encourage them to devoure men alive. They are always directed by a little specled fish, called a pilot fish, by guiding their Monster-masters to a prey.’7 In Mauritius, he watched the Dodo:

‘Her body is round and fat … so great as few of them weigh less than fifty pound: meat it is with some, but better to the eye than stomach; such as only a strong appetite can vanquish.’8

Today, Herbert is perhaps better known for acting as guardian to Charles I during the King’s captivity; in this capacity, he showed great consideration and kindness and was so overcome that he was unable to witness Charles’ execution. On his death-bed, Herbert confessed that, ‘I held their Clothes, whilst they murthered him, but … I never consented to his Death; I ever pray’d and endeavoured what I could against it’.9 However, Herbert also deserves to be remembered for the enthusiasm, immediacy and scholarship of his earlier travel writing – ‘The “other”, for Herbert, is endlessly fascinating; he describes it as well as he can, knowing that it cannot be contained or controlled’.10

Today, Herbert is perhaps better known for acting as guardian to Charles I during the King’s captivity; in this capacity, he showed great consideration and kindness and was so overcome that he was unable to witness Charles’ execution. On his death-bed, Herbert confessed that, ‘I held their Clothes, whilst they murthered him, but … I never consented to his Death; I ever pray’d and endeavoured what I could against it’.9 However, Herbert also deserves to be remembered for the enthusiasm, immediacy and scholarship of his earlier travel writing – ‘The “other”, for Herbert, is endlessly fascinating; he describes it as well as he can, knowing that it cannot be contained or controlled’.10

Sir Thomas Herbert, A Relation of Some Yeares Travaile, Begunne Anno 1626 …, (London, 1634), 1p. 92, 2p. 92, 3p. 112, 4p. 169, 5p.127, 6p. 39, 7p. 5, SCM 09672

8Sir Thomas Herbert, Some Years Travels into Divers Parts of Africa and Asia the Great …, (London, 1677), pp. 382-3, SCT 00254

9Sir Thomas Herbert, Memoirs of the Last Two Years of the Reign of … King Charles I, (London, 1702), p. 301, SCM 10875

10John Butler, ‘Herbert, Thomas’ from Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/herbert-thomas-2

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Your library might like to know that I have edited Sir Thomas Herbert’s Travels in Africa, Persia and Asia the Great (Tempe: Arizona Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2012). It was good to see Herbert’s book featured on your website.