This is an account of my initial attempt to find learning theory to underpin and inform the development of our Digital Literacies framework and its implementation, as part of the LLI’s involvement in the university’s Digital Campus strategy. I drew upon literacies research and on the conclusions from my own MSc research into the adoption of digital technologies in a university.

Why a literacies approach?

Digital allows and requires new pedagogical approaches, but the mediation doesn’t alter that what we are talking about is reading and writing in a university. Academic literacies research provides a robust and established framework “which has already made a significant contribution to understanding learning in a range of educational contexts, including those that are digitally mediated” (Lea & Jones, 2011 p.7-8). It is a sociocultural view of literacy as situated social practices, rather than a narrowly focused functional approach about individual cognitive skills – learning rules and conventions about spelling, grammar, and style, which assumes those skills could be easily ported from context to context (Lea & Street, 2006).

At the heart of such an approach is the critical engagement with texts, or digital technologies.

The ethos for an academic literacies approach comes from a belief that:

- universities have a transformational role in society;

- we need joined up thinking not technological determinism when it comes to teaching and learning with technology (Kirkwood, 2014); and

- digital literacies are emancipatory.

The definition of digital capabilities in the JISC framework (until recently they called them ‘digital literacies’) is ‘those capabilities which fit an individual for living, learning and working in a digital society’ (JISC, 2017). However, as Professor Mark Brown (National institute for Digital Learning, Dublin City University) suggests, if digital literacy is core to what it means to be a digital citizen in the 21st century, then we need to go beyond preparing people to ‘fit’ the inequitable and unjust societies that we have created. We should instead prepare them to challenge and reshape such societies (Brown, 2017).

Combining a literacies approach with an engagement model

I found parallels between Lea and Street’s conceptualisation of academic writing, and Bennett’s Digital Practitioner Framework (Bennett, 2014), (Sharpe & Beetham, 2010).

Lea and Street’s three models of academic writing

Mary Lea and Brian Street (2006) argued that research into student writing could be conceptualised into three overlapping models:

- Study Skills – this is literacy as an individual cognitive skill. The emphasis is on surface level aspects such as spelling and grammar. The skills can be moved unproblematically from one context to another.

- Academic Socialisation – the acculturation into an academic discipline. Learning to speak, think and write like a sociologist, or a biologist, for example.

- Academic Literacies – concerned with meaning making, power and authority, and what counts as knowledge in any particular academic context.

The models overlap, and encapsulate each other. They do not imply a hierarchical linear progression from bottom to top.

Bennett’s Digital Practitioner Framework

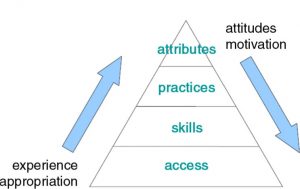

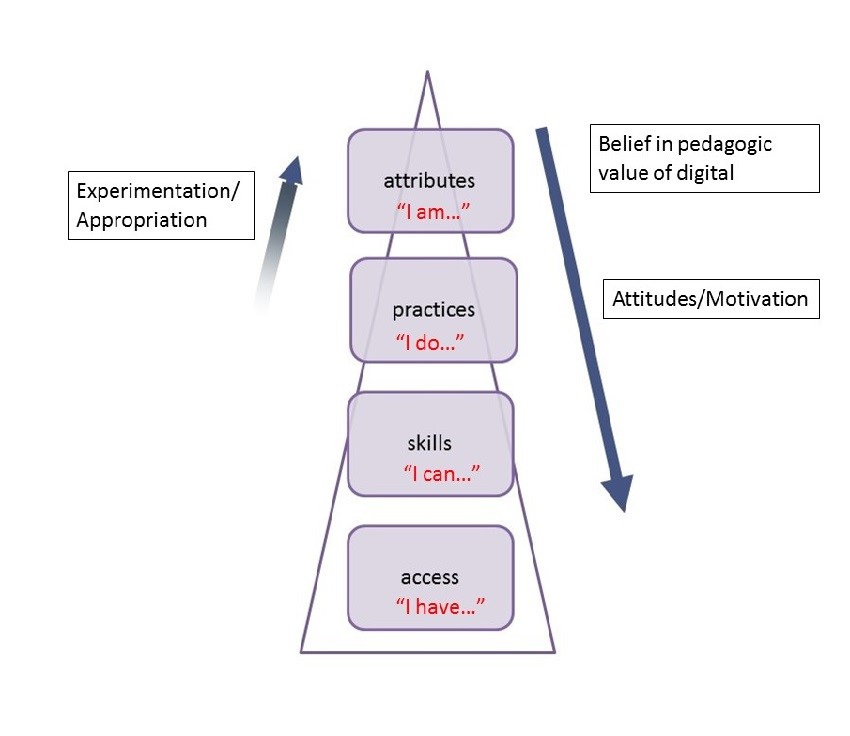

Sharpe and Beetham (2010) proposed a model of engagement with technology based on student digital literacies. The left-hand arrow suggests how access can drive the development of skills, and in turn effective practices which results in the identification with the attributes of a confident digital learner. The right-hand arrow suggests that these attributes drive the motivation to learn new practices, develop skills, and get access (Bennett, 2014).

Bennett amended it to consider academic staff.

In this model, ‘attributes’ refers to ways of thinking about technologies, developing a digital mindset, a belief in the pedagogic value of digital technology and providing the motivation to learn more. Lecturers assimilate practices into a sense of being.

As with the three models approach to literacies, this is not meant to suggest a linear progression. People can be at different stages in different contexts and different areas of practice.

Bennett found that academics were not interested in skills per se, and were more interested in achieving pedagogical goals than in becoming ‘digital practitioners’. The shorter arrow on the left-hand side suggests that successful adoption of a technology will shape a lecturer’s belief about its value. Those who have the confidence will experiment with, and adopt technologies, appreciating the pedagogic value of those technologies. This provides the motivation to learn more, and to get what skills might be necessary to implement particular approaches. This belief in the pedagogic value of technology involves the critical engagement with technology that signifies a digitally literate practitioner.

What this model suggests is that a person can be digitally literate – that is, engage critically with digital technology, but in theory may not have any functional skills or access to relevant technology. It also suggests that a person can be highly skilled in the use of technology and software applications, but have no idea how to put them to good pedagogical use. In other words, skills and access are not sufficient for digital literacy. Digital literacy requires critical engagement with practice and an appreciation of the appropriate use of digital technologies for teaching and learning.

This view is supported by Powell and Varga-Atkins who acknowledge the importance of functional access, skills and practice, but suggest that when viewed through a critical lens, digital literacies have both an epistemological impact and an ontological element. This can be seen in their definition of a digitally literate person:

“A digitally literate individual is able cognisantly contribute to and extend knowledge in digital contexts and understands the impact of the digital on knowledge itself as well as upon new ways of knowing.” (emphasis is mine). (Powell & Varga-Atkins, 2013 p.8)

Putting the two models together

There are parallels between Lea and Street’s model of academic literacies, and Bennett’s model of engagement with digital technologies for learning and teaching. This is not a framework for digital Literacies. It is a theoretical underpinning, and a means of developing practice.

The rationale for a literacies approach

My own research (for my MSc in Digital Education) suggests that:

- Among academics it is crucial to develop a sense of agency and autonomy via a scholarly approach (Kirkwood & Price, 2013) to the adoption of digital technologies.

- By a scholarly approach I mean a reflective and critical engagement with literature and research to inform approaches to teaching and learning in collaboration with colleagues.

- Agency and autonomy, and the sustainability of the adoption of digital technology, are also supported by understanding local contexts and the cultural configuration of the institution.

- Digital technology should be seen as part of the context of education – as a part of the complex weave of practices, values, spaces, and organisational politics.

In addition, the rationale for an academic literacies approach to underpin a digital literacies framework is that:

- As an established (but contested) academic discipline it provides robustness and credibility.

- It provides the basis for a critical approach to the use of digital technologies, which is the essence of digital literacies.

- It is against an instrumentalist skills development agenda.

- It allows for a scholarly approach.

- Academics can model disciplinary digital behaviour to students, which gives them a sense of agency and ownership and plays to their strengths as researchers.

- It encourages a ‘post-digital’ viewpoint that removes the demarcation between digital and non-digital. Instead of ‘digital education’, it is just education, or instead of ‘e-learning’ it is just learning.

- This is not to suggest that everything defaults to digital, because that ignores local contexts and practices. Instead it encourages a critical approach in which ‘not digital’ is a legitimate option. Suggesting that everything should be digital removes the agency in making choices about what is best practice in a given context, and normalises technology use.

- A ‘post-digital’ view allows us to position technology as a part of the context, or learning ecology, and not something separate that is brought in to ‘enhance’ existing practice. Technology is as much a part of the educational environment as lecture theatres and text books, staff and students.

I think that academic literacies could underpin a contextualised approach that supports behavioural change, focused on attributes and attitudes, rather than a narrow focus on skills development. Combined with the model of adoption it could provide a framework for the sustainable development of digital literacies as critical and reflective practice.

Your comments and criticisms are welcome.

Header image: Molecule by Caroline Davis2010 CC BY 4.0

References

Bennett, L. (2014). Learning from the early adopters : Developing the digital practitioner. Research in Learning Technology, 22, 1-13.

Brown, M. (2017). Exploring the underbelly of digital literacies. Retrieved from https://oeb-insights.com/exploring-the-underbelly-of-digital-literacies/

JISC. (2017). Organisational digital capability in context. Retrieved from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developing-organisational-approaches-to-digital-capability/organisational-digital-capability-in-context

Kirkwood, A. (2014). Teaching and learning with technology in higher education: Blended and distance education needs ‘joined-up thinking’ rather than technological determinism. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 29, 1-16. doi:10.1080/02680513.2015.1009884

Kirkwood, A., & Price, L. (2013). Missing: Evidence of a scholarly approach to teaching and learning with technology in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 18, 327-337. doi:10.1080/13562517.2013.773419

Lea, M., & Jones, S. (2011). Digital literacies in higher education: Exploring textual and technological practice. Studies in Higher Education, 36, 377-393. doi:10.1080/03075071003664021

Lea, M., & Street, B. (2006). The “academic literacies” model: Theory and applications. Theory into Practice, 45, 346-351. doi://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4504_11

Powell, S. S., & Varga-Atkins, T. (2013). ‘Digital literacies: A study of perspectives and practices of academic staff’: A project report. written for the SEDA small grants scheme. Liverpool: SEDA.

Sharpe, R., & Beetham, H. (2010). Understanding students’ uses of technology for learning: Towards creative appropriation. In R. Sharpe, & H. Beetham (Eds.), Rethinking Learning for a Digital Age: How Learners are Shaping their Own Experiences (pp. 85-99): Routledge.

Subscribe to Stephen Walker's posts

Subscribe to Stephen Walker's posts

Recent Comments